Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: Blind man’s bluff in Iraq

Nov 20, 2024 | Paul Monk

The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the United States and the Middle East, 1979-2003

The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the United States and the Middle East, 1979-2003

by Steve Coll

Penguin Random House, 2024, 556 pp, $65.00

Steve Coll, former Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University and a long-time staff writer for the New Yorker, is the author of a string of books, dating back to the late 1980s, on corporate America (The Deal of the Century, The Taking of Getty Oil) and on secret intelligence (Ghost Wars, Directorate S).

This latest book is a much-needed contribution both to retrospective understanding of how the United States came to invade Iraq in 2003, and the broader question of how US intelligence assessments and foreign policy are made. It is more than usually topical, given the uncertainties following the presidential election in the US, to say nothing of the challenge with which Iran now confronts us all.

The book concludes just as the Iraq War begins in March 2003. In the weeks prior to the onset of war, there was a great deal of passionate debate as to whether the planned invasion was justified. Bob Hawke, long retired but a respected elder statesman, declared publicly that it was not. Such an invasion, he declared, “would be illegal, immoral and stupid.” Many others agreed.

I wrote, in an essay which appeared in the Australian Financial Review the day the war started, that the matter was not as clearcut as that, but that if the US overthrew Saddam Hussein only to get bogged down in a prolonged and bloody urban guerrilla war, the invasion would come to seem a stupid strategic decision. That’s what happened.

Philip Bobbitt would write, in Terror and Consent (2008) that it had been a war of choice, not of necessity, with a very messy outcome, but we needed to ask how things may have turned out had the US not overthrown Saddam.

In The Achilles Trap, Steve Coll takes us back along the tortuous path which led to the US invasion. He focusses upon three things: American perceptions of Saddam Hussein over time; Saddam’s perceptions of America, from wary cooperation against Iran to war with the US; and Saddam’s ambition to develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and how this led to the US invasion.

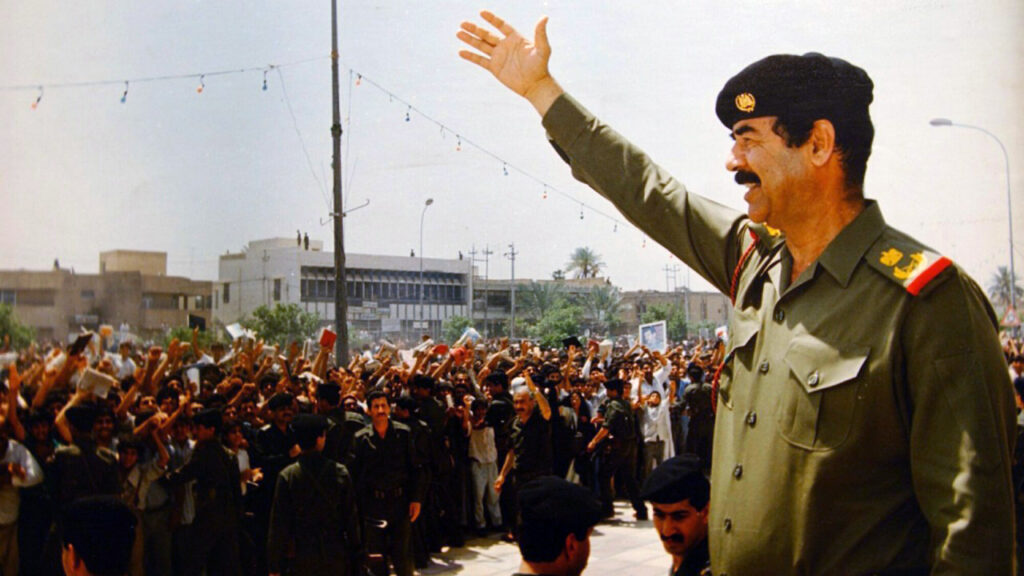

The book is divided into three chronologically ordered parts: “The Enemy of My Enemy” (December 1979 to August 1990), “The Liar’s Truths” (August 1990 to September 2001) and “Blind Man’s Bluff” (September 2001 to March 2003). The enemy in Part One was Iran, or more precisely the radical Shi’ite regime in Teheran and its militant wing, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The liar of Part Two is Saddam himself, who played an elaborate and prolonged shell game with his WMD after his defeat in the (first) Gulf War. This generated genuine confusion in US intelligence and at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The “blind man’s bluff” of Part Three refers to Saddam’s blindness to the consequences of his own game of bluff. Coll’s unpicking of all this is meticulous and illuminating. It centres on the paradox that Saddam believed the CIA was omniscient. He therefore interpreted American behaviour based on the assumption that official Washington knew what he knew and that its insistence it was uncertain about his WMD programs was all Machiavellian bluff. His counter bluff was to keep playing his shell game, in the belief that he could thereby deter US invasion and rally Arab allies. He got it exactly wrong.

The most significant oversight in the book is that having titled his book The Achilles Trap, Coll doesn’t mention, much less explain, that title until page 283. It turns out that the CIA’s file cryptonym for covert operations against Saddam was ‘DB Achilles’, where DB was coding for matters pertaining to Iraq and ‘Achilles’ the codename for Saddam. The title of the book was very well chosen, but it would have been good to explain it at the start.

Here is the key passage:

Saddam himself had cited the Achilles myth while rallying Arab neighbours in 1990 to his coming war against America. For both the Iraqi dictator and the CIA, the example of the Homeric hero with a vulnerable heel offered a call to action, despite long odds. Saddam regarded America as too hubristic and too afraid of taking casualties to defeat a united Arab nation, which he hoped to forge through his own leadership… The CIA’s operatives and leaders embraced hope over experience as they searched for a coup plan that might work. Both sides, therefore, trapped themselves by imagining a fatal flaw in their opponent that did not actually exist.

Both paid the penalty for this. Saddam’s country was invaded and he was overthrown, captured, tried and executed. The United States was drawn into a long, bloody war and its national security establishment and executive lost a good deal of credibility as a consequence.

Saddam’s phobic belief that the CIA was all-knowing was of a piece with his visceral anti-Zionism and antisemitism. He believed the US intended to facilitate Israeli conquest of the Middle East and the creation of a Jewish empire. Coll shows us how this played out. What Saddam saw as manipulative genius on the part of Washington was actually staggering incompetence.

This theme is of vital importance in our current circumstances, not least in trying to read the thinking in Teheran. Are the ayatollahs and the IRGC reading The Achilles Trap, as a wider war looms in the Middle East? What lessons will they think they can learn? Almost certainly the wrong ones. Having reportedly interrogated the head of the IRGC on charges of having spied for Israel, and witnessed the stunning decapitation of Hezbollah by the ‘Little Satan’, will they see the ‘Great Satan’ as incompetent, or as Machiavellian?

In any case, the centrepiece of Coll’s analysis is his careful reconstruction of the WMD programs Saddam did have, in the 1980s; the astonishment of the CIA and IAEA, in 1990-91, when they discovered how large and advanced these programs had been; and the way in which Saddam’s shell game for more than a decade after that confused his own scientists and generals and confounded IAEA and Western intelligence analysts. This history is vital in correcting widespread and partial “narratives” about WMD and the Iraq war.

Coll begins his book with the observation that the discovery, by the Iraq Survey Group (ISG), that Saddam did not have WMD, came as a “shock” and a “revelation”. The ISG’s mission abruptly shifted from hunting for WMD to sifting truth from misperception and fabrication in the history of Saddam’s regime.

Coll himself was in Iraq, on assignment for the Washington Post, from October 2003 as this unfolded. It is vital to register this sense of ISG shock and bewilderment, which gave Coll what would become the theme of this book, years later.

In late 2003, he spoke with David Kay, the ISG head, and found:

He was exploring a theory that Saddam had been bluffing – pretending that he might have WMD in order to deter the radical ayatollahs from attacking Iraq. And yet the matter seemed uncertain, Kay told me, since Saddam did not appear to have been particularly afraid of Iran. When one of his ministers had worried aloud that Iran might pursue its own nuclear or chemical arsenal, Saddam had reportedly replied, ‘Don’t worry about the Iranians. If they ever get WMD, the Americans and the Israelis will destroy them.’

It’s almost eerie reading that in 2024, as American and Israeli alarm over Iran’s nuclear aspirations and Iran’s aggressive and prolonged offensive against both Israel and the United States in the Middle East have us all on the brink of a large-scale war.

But that is to read through the lens of hindsight. What Coll has provided is a history which enables us to comprehend how things unfolded in reality – through a generation of missteps and mutual misperceptions, when no-one had the benefit of hindsight. Saddam poured resources into a very large WMD program, then destroyed his WMD stocks, while insisting that his own scientists and security agencies systematically conceal that this had been done.

This is the kernel of Coll’s book, and it warrants close reading.

The overarching theme of the book, however, is as he writes, “The trouble American decision-makers had in assessing Saddam’s resentments and managing his inconsistencies.”

He adds that the lessons from this are more important than ever as we seek to deal with a whole set of autocrats in the 2020s.

Saddam Hussein, like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Ali Khamenei and Kim Jong-Un, was a conspiracy theorist. He was paranoid. But as the old poster of half a century put it, ‘Just because you are paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.’ Saddam was a murderous and aggressive tyrant, and his enemies were out to get him. They did. And Iran?

Paul Monk did his PhD on US counterinsurgency strategies throughout the Cold War in Southeast Asia and Central America. He subsequently worked in the Defence Intelligence Organisation, where he became head of the China desk in 1994.

Tags: Iraq, Middle East, Saddam Hussein, United States, WMD