Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: A Revolt that Still Reverberates

Jun 29, 2023 | Allon Lee

Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict

Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict

Oren Kessler

Rowman & Littlefield, Feb. 2023, 334 pp., A$ 57.99

Oren Kessler’s book covers the seminal events of the three-year bloody uprising by Palestinian Arabs against British rule and increasing Jewish immigration from Europe to Mandatory Palestine.

Many of the dramatis personae may be unfamiliar to modern readers, yet the terminology and scenarios are instantly recognisable: terror, boycotts, betrayals, inquiries, riots, pogroms, antisemitism masquerading as anti-Zionism, negotiations rejected, moderates permanently silenced, house demolitions, civilians indiscriminately slaughtered, security barriers and collective punishment, to name just a few.

The book’s main contention is that the Revolt in the short term dealt a mortal blow to Palestinian Arab society, which then contributed to its failures in 1947/48 and, longer term, set the contours for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as we know it today.

The statistics tell the tale, as Kessler notes:

The Great Revolt… exacted a withering toll… About 500 Jews had been killed… British troops and police suffered around 250 fatalities… But the most onerous price of all was paid by the Arabs themselves: At least 5,000… were dead, of whom at least 1,500 likely fell at Arab hands… As many as 2,000 homes were demolished. Forty thousand people had fled the country… disproportionately representing the political, commercial, and landed elite. The Arab economy was crippled. Crops had dried up as landowners fled and peasants were required to provision, feed, and fund thousands of armed men. Thousands of Arabs lost government jobs due to reduced public revenues and doubts over their allegiance… the Arab boycott of Jewish businesses and buyers, which continued informally throughout the revolt, slashed Arab income. Half of all cargo that once passed through the port at Jaffa was now diverted to the Jews’ port at Tel Aviv.

Kessler shows great skill in his thumbnail portraits of British, Arab and Jewish figures in Mandate Palestine, whilst situating them in the context of a world on the precipice of all-out war.

On the Jewish side there is the double act of Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion.

Weizmann, tall and urbane, is charming and scolding in equal measure on the international stage. Ben-Gurion – stocky and humourless, yet, Kessler says, he immediately grasped the nationalist underpinnings of the Revolt and saw an opportunity for the Yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine) which paid off when Jewish statehood arrived in 1948.

The British officials running the Mandate, Kessler notes, may have admired the Yishuv’s achievements but were more partial towards the Arabs than the Jews.

However, he notes, there were also extraordinary figures in the Mandate – mainly Christian Zionists – who counterbalanced this bias, offering critical assistance in the development of the Yishuv.

This includes the Australian-born Lewis Yelland Andrews, appointed district commissioner of the Galilee and guided by a belief that the Jewish people’s return to Israel would expedite the return of the Christian Messiah.

Driven by similar motives was the legendary figure Orde Wingate, whose creative thinking was instrumental in halting Arab sabotage of oil pipelines at night. The Yishuv’s eventual successes during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948 are traced in large part back to the training Jews received from Wingate to assist in counterterrorism operations during this period.

Kessler argues that the counterinsurgency methods used by the British to quell the Revolt were often indistinguishable from atrocities. When an army truck drove over a land mine, killing four soldiers on board, troops went to the nearest Arab village and machine-gunned and torched it. They forced 20 men onto a bus, ordering the driver to travel down a road where a land mine was buried, with inevitable consequences.

The cast of Palestinian Arab leaders Kessler focuses on in finer detail are individuals who favoured an accommodation with the Yishuv and privately abhorred the rising death toll from internecine Arab violence. This includes Musa Alami, who enjoyed a cordial relationship with Ben-Gurion that stretched from the 1930s until the latter’s passing in 1973.

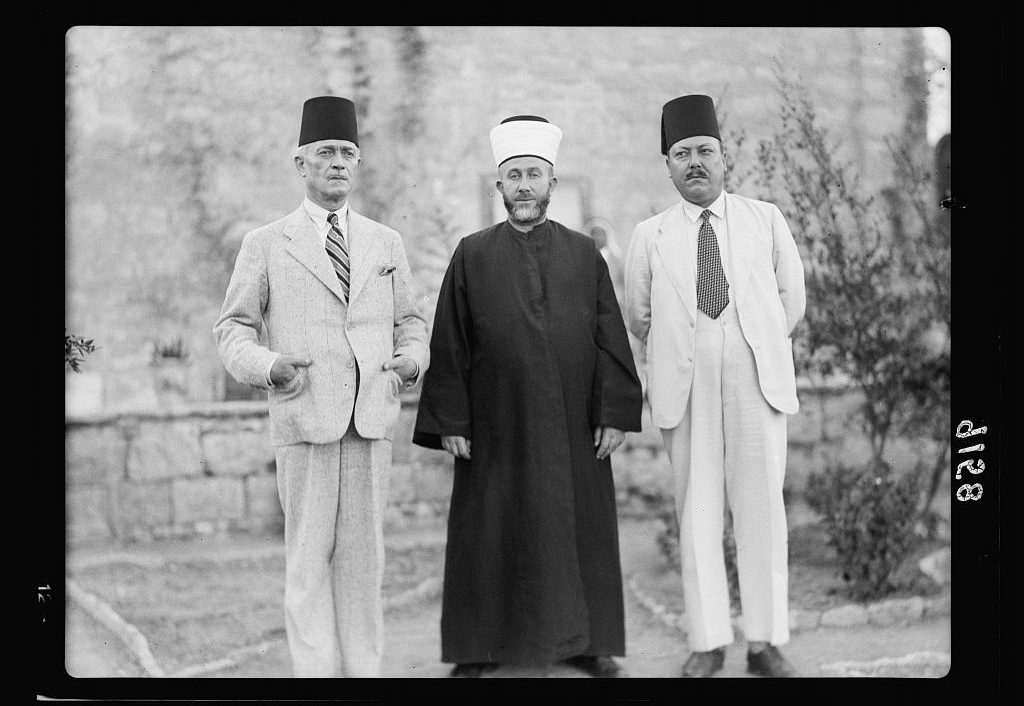

The villain of Palestine 1936: Haj Amin al-Husseini with members of the Arab Higher Committee (Image: Picryl)

The villain of the book is the infamous Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem. Kessler demonstrates that Britain’s greatest mistake was to elevate al-Husseini to the leadership of Palestine’s Arabs in the 1920s.

Kessler is unsparing in his portrayal of a leader who is unwilling to compromise, continually expresses his opposition to Zionism in antisemitic terms, ruthlessly condemns hundreds of his own people to death for daring to fraternise with Jews, and consistently plays the role of spoiler.

No one, including especially his Arab peers, has a good word to say about the Mufti, whose obsession with preventing Jews from reaching Palestine drove him to collaborate with the Nazis at the highest levels. As Kessler notes, the Mufti’s own memoirs admit that as early as 1943, he learnt from Heinrich Himmler that the Nazis had already killed three million Jews. The Mufti’s own ignoble efforts included recruiting two divisions of Bosnian Muslims for the Waffen-SS and broadcasting Nazi-themed antisemitic propaganda in Arabic from Berlin.

The final part of the book details the series of inquiries set up by Britain to create a political horizon that would dampen Arab incentives to resume their campaigns of violent terror.

Kessler records Ben-Gurion’s enthusiasm for the 1937 Peel Commission’s proposal to partition Palestine into a large Arab state and a tiny Jewish state, believing it “dwarfed” the Balfour Declaration in importance. Jews would have their own state with a “Jewish army” and access to the sea to permit large-scale immigration, he notes.

Yet this proved to be a false dawn. The storm clouds of another world war convinced London to capitulate in the face of the resumption of Arab terror – which it had largely subdued – amid fears that the wider Middle East could back Nazi Germany. The 1938 Woodhead Commission, pithily called “Re-Peel”, essentially gutted the Mandate’s original rationale – namely, to facilitate Jewish immigration to Palestine and the creation of a Jewish national home – just when European Jewry most needed a safe haven.

The book’s account of the London conference in February 1939, organised to try to reach an understanding between Arabs and Jews, is fascinating, if sadly predictable.

British PM Neville Chamberlain delivered his opening remarks twice because the Palestinian Arab delegates – under the strict orders of the Mufti – refused to be in the same room as their Jewish counterparts.

Arab dignitaries from other countries relented, and Kessler writes that Ben-Gurion and a former Egyptian PM conversed directly in Turkish.

Ultimately, Britain adopted a plan restricting Jewish immigration to a mere 75,000 over the next five years, after which Palestinian Arabs would exercise a veto over intake numbers. An independent Palestinian state – which would be neither Arab nor Jewish – would be created at the end of ten years.

There was widespread rejoicing by Palestinian Arabs when they heard the details, Kessler notes.

Fourteen members of the Arab Higher Committee wanted to vote in favour, but the 15th member was the only voice that mattered – the Mufti, who overruled them and rejected the British plan.

Nonetheless, Britain’s 1939 acquiescence to the Mufti’s demands was his high-water mark as leader, Kessler notes, and ended the Revolt.

The price paid by Palestinian Arabs is summed up in a quote from Yusuf Hanna, editor of the Filastin newspaper, who opined, “There is not an Arab who wants to see himself ruled by the Jews, but there is not also an Arab with sense who wants to see himself ruled by assassins.”

Unsurprisingly, the Mufti went on to reject the 1947 UN Partition Plan and his political heirs to this day continue his legacy of opposition.

Aside from the book’s last chapter, Kessler largely avoids editorial comment, letting events and protagonists speak for themselves.

With the shadow of the Holocaust a constant backdrop, Kessler doesn’t need to telegraph why Jews were desperate to settle in Palestine and secure their own state. Indeed, Kessler shows that not all of the antisemitism emanated from Nazi Germany, relaying how Poland’s ambassador in London called for Britain to give Palestine to the Jews so his country could be rid of them.

Perhaps the most poignant section in the book is Chaim Weizmann’s weary and dark address in Geneva on the last night of the last World Zionist Congress before WWII – which started only a week later. “Many in the audience wept”, Kessler records, knowing war was imminent, adding, “most of the Eastern European Jews were never seen again.”

While Palestine 1936 is easy to read, much of what it records is not easy to accept and digest.

But it stands as an essential reminder that many of the setbacks experienced by Palestinian Arabs are the result of the poor choices made by their own leaders dating all the way back to the 1920s.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians