Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: A mass emigration of criminals

Aug 14, 2024 | Efraim Zuroff

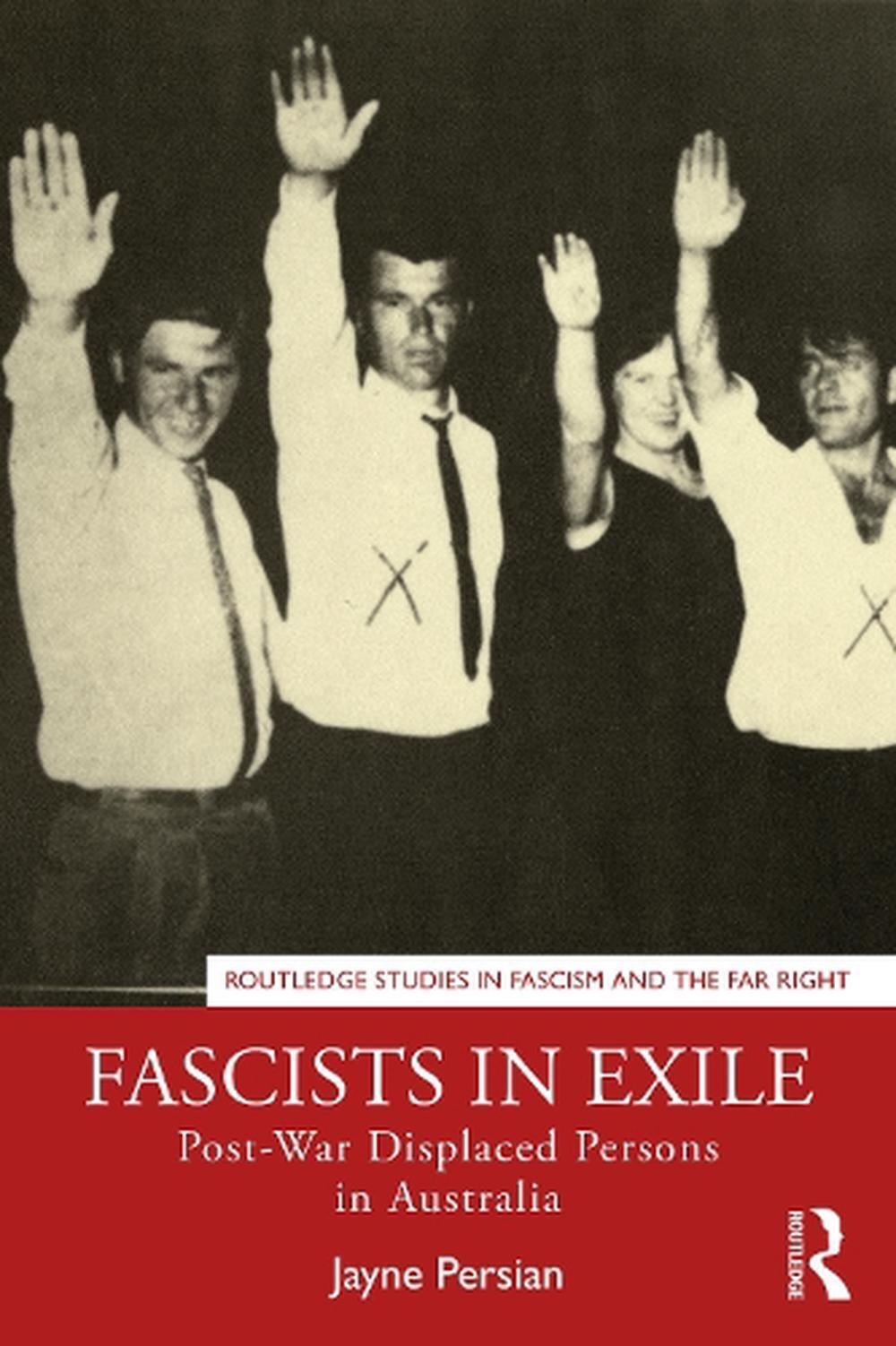

Fascists in Exile: Post-War Displaced Persons in Australia

Fascists in Exile: Post-War Displaced Persons in Australia

Jayne Persian

Routledge, 182 pages, A$49.99

One of the strangest outcomes of World War II was the mass postwar emigration of Nazi war criminals to the Anglo-Saxon democracies which fought against the Nazis and played a major role in the defeat of the Third Reich. Thus, for example, some 200,000 American soldiers lost their lives fighting against the Germans, yet an estimated 10,000 Nazi perpetrators were admitted as immigrants to the United States during the decade after the war. And a similar situation developed in Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The only exception in this regard was South Africa, which was hermetically closed to immigration in the aftermath of World War II.

For more than three decades in the United States, and more than 40 years in the other Anglo-Saxon democracies, no effort was undertaken to identify, investigate, and if possible, prosecute any of these perpetrators. But as knowledge and interest in the Holocaust grew throughout the world, efforts to bring these criminals to justice were launched.

The first government to take steps to enable the prosecution of the Holocaust perpetrators, who had immigrated by lying about their service with the Nazis, was the United States, which established its Office of Special Investigations in 1979. Nazi collaborators were stripped of their American citizenship, and could then be deported. Eight years later, Canada passed a law enabling criminal prosecution of Nazi criminals, and in 1989, Australia passed a similar law. In the UK, it took almost another five years to pass similar legislation in 1991. The only country which refused to take legal action against immigrants who lied about their service with the Nazis was New Zealand.

Now that at least three and a half decades have passed since the efforts to prosecute these perpetrators commenced, and there is no political will in any of these countries to bring ninety-year-olds to justice, the time has come for historians to assess the results. So far, two books on the “belated” trials of Holocaust perpetrators in Anglo-Saxon countries have been published this year – Safe Haven by Jon Silverman and Robert Sherwood on Great Britain, and Jayne Persian’s Fascists in Exile on Australia.

The latter is the subject of this review, and well deserving of public attention. Anyone interested in post-Holocaust justice, the history of Australian Jewry, the critical role of Eastern European Nazi collaborators in the Final Solution, and related topics will find this book of great interest. Unlike Safe Haven, which covers the history of the issue starting with the passage of the British War Crimes Act in 1991 (after a heated struggle that took four and a half years with fierce opposition by the House of Lords, which twice rejected the bill), Fascists in Exile covers the entire issue, from the post-World War II emigration of the Eastern European refugees to Australia to the present.

Persian does an excellent job of exposing the serious flaws in the screening, or the lack thereof, both in Europe prior to immigration and in Australia after arrival. During the years 1947 to 1952, 170,000 non-Jewish Displaced Persons settled in Australia, the overwhelming majority of whom were Eastern Europeans from countries in which the local population actively participated in the mass murder of the local Jewish population. Although there was extensive information available on the World War II service of such individuals, hardly any effort was made by the International Refugee Organisation to prevent their immigration, or even inform the Australian authorities about their past.

Persian explains in great detail what went wrong in Europe, as well as in Australia. First of all, in Europe, most of the investigations were carried out by inexperienced officers and enlisted men, who were not aware of the role played by Eastern European Nazi collaborators in the Holocaust. To make things worse, the British Foreign Ministry instructed its military officers to protect the 20,000 members of the Latvian SS Legion, who fought for the victory of the Third Reich. Quite a few of the Latvia SS Legion’s members joined after serving in the Arajs Kommando mass murder squad, or the Latvian SD, both of which played major roles in the annihilation of Latvian Jews, as well as German and Austrian Jews deported to Latvia.

Another example of the totally irresponsible screening of large numbers of prospective immigrants occurred with respect to the Ukrainians of the Galicia Division of the SS, which also participated in the mass murder of Jews. Only 180 out of 8,000 men were interviewed individually. Thus is it not at all surprising that the IRO acceptance rate for immigration was 82.6%.

To make matters worse, all the flaws in the screening process in Europe were exacerbated by the policies of the Australian government, which believed that once the IRO vetted the refugees, they were no longer responsible for any additional security checks. In addition, the major concern of the Australian government was that the refugees would fit into “White Australia”, and help solve the country’s population and labour force deficits. In effect, their only concern was that the new arrivals might join and strengthen local fascist organisations.

To add insult to injury, the only Europeans whose immigration to Australia was considered undesirable by the government were Jews. In the words of an Australian immigration official quoted by Persian, “We have never wanted these people and still don’t want them.” And in instructions sent in 1949 to the Australian mission in Europe, the staff were instructed that “The term [Jewish] referred to race and not religion and the fact that some DP’s who are Jewish by race have become Christian by religion is not relevant.”

Given this attitude, it is not surprising that all the protests and warnings, especially by Jewish activists, about the immigration to Australia of Nazi collaborators were ignored or summarily dismissed. All this changed in 1983, in the wake of the ouster from power of the Liberal Party, which was the political home of the overwhelming majority of the right-wing Eastern European refugees. Labor was open to investigating the Nazi war criminals who had immigrated to Australia, and the combination of the deportation of Latvian suspect Konrad Kalejs from the US to Australia, and a five-part exposé on radio and TV by journalist Mark Aarons, led to the 1986 decision to establish an official government inquiry, headed by Andrew Menzies, a former deputy secretary in the Attorney-General’s Department.

The final chapters of the book are devoted to the efforts of the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), which was established in 1987 by the government as a result of the findings of the Menzies investigation. It opened with a total of 841 files, but according to Persian, that figure is misleading since some suspects had two or three files. The country of origin with the highest number of suspect files was Lithuania with 238, followed by Latvia with 111, Ukraine with 84, Hungary with 45, and Croatia with 44 (The Simon Wiesenthal Center’s office in Jerusalem sent the Australian authorities a total of 487 suspects, mostly from the Baltics, between 1986 and 2005). Two hundred and forty-eight of the suspects were not located in Australia, and 262 persons were assumed to be deceased due to their advanced age.

According to Persian, SIU interviews of suspects were a fairly informal process, which relied on a cooperative interviewee. Suspects could simply refuse to be interviewed, others simply answered “No comment, no comment.” In case after case, it was clear that the suspects had served in killing squads, but no one admitted that they had committed murder, nor were there any eyewitnesses who could testify that a certain suspect had committed murder. Thus, it was not surprising that the first three prosecutions failed, which gave the government of Paul Keating an excuse to close down the SIU long before it finished its task.

There are a few factual mistakes in Jayne Persian’s book that should be mentioned. The American OSI won cases against slightly more than 100 Holocaust perpetrators, not against “several hundred people”. Canada only prosecuted one case on criminal charges, not three. And Persian failed to mention the successful prosecution in Germany of Ernst Hering, who was discovered due to the (failed) trial in Australia of Heinrich Wagner, who served in the same unit that murdered 104 Jews in Israelovka, Ukraine. She also failed to mention the jailing of Karoly Zentai, who sat in prison in Perth for several months awaiting extradition to Hungary to face charges for the murder of Peter Balasz, an 18-year-old Jewish boy whom he caught in Budapest on a tram without the obligatory yellow star.

Despite these facts, Persian’s book is extremely informative, and well-researched and written, and should be required reading in every Australian high school and university.

Dr Efraim Zuroff is the chief Nazi hunter of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Director of the Center’s Israel Office and Eastern European Affairs.

Tags: Australia, Holocaust/ War Crimes