Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: A Bob One Way

May 25, 2023 | Allon Lee

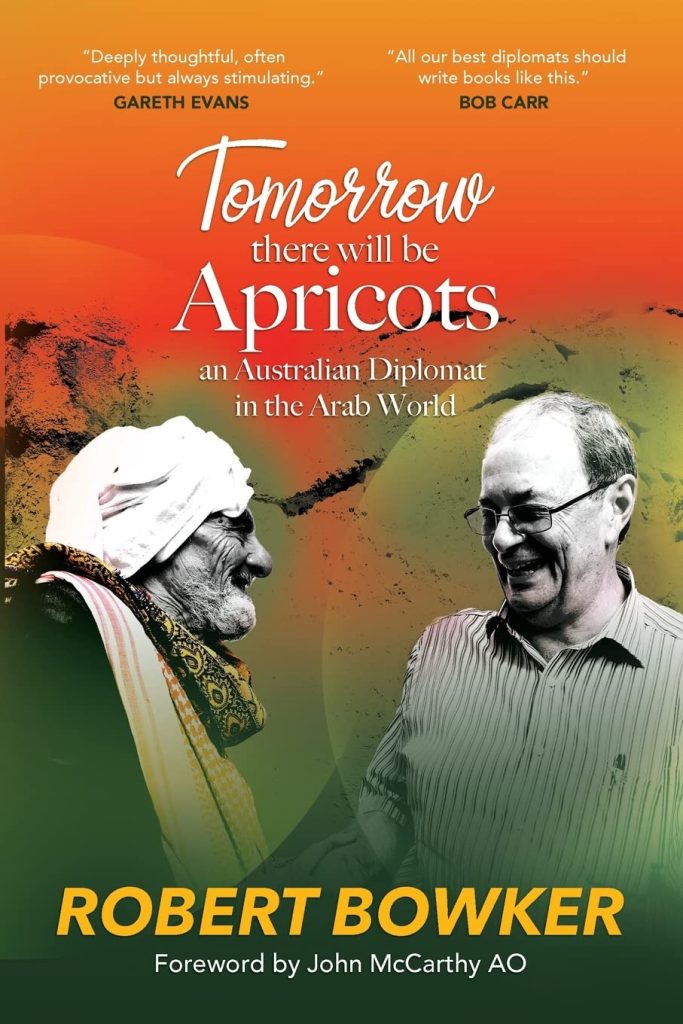

Tomorrow there will be Apricots

Tomorrow there will be Apricots

Robert Bowker

Shawline Publishing Group, Oct. 2022, 307 pp, A$36.95

Former Australian career diplomat Robert “Bob” Bowker’s new book Tomorrow There Will be Apricots provides a window into one man’s experiences representing his country in the Middle East from 1971 until his retirement in 2008.

A book of two halves, the first part focusses on Bowker’s career, while the second part shifts gears and summarises Bowker’s thoughts on a range of topics – Israel/Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Iran, the failure of the Arab Spring, Islamism, etc.

From the get-go, Bowker describes himself as a Middle East tragic and says being an “Australian diplomat in the Arab world… was my life.” It shows.

He writes that his “personal interest in Islam began during my student days in Indonesia,” but it was in Malaysia that “my professional interest in the Islamic world” began.

Bowker admits he had to struggle to remain professionally detached, writing that “I had to be on my guard against allowing fascination, if not empathy… to interfere with hard-edged analysis of major issues. A dilemma that persists with me to this day is how to pay due heed to the poetic power of mythologies and memories, real and imagined, without losing critical perspective.”

For this reviewer, given his frank admissions throughout the book, this appears to be a battle that Bowker may have lost.

His first sustained exposure to the Middle East was a posting in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in early 1974, just as the first Arab oil embargo was at its height.

In Jeddah, Bowker writes, “mostly I enjoyed the company of Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian expatriates” and would fly every few months to Beirut and visit other capitals, including Cairo and Teheran.

Returning to Australia, he served on the Middle East desk. The pro-Palestinian opinions he had developed appear to have never been far from the surface.

Tasked with providing analysis in 1976 of how “a negotiated solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict” might look, Bowker’s advice was that “Israel risked being seen as an apartheid state… if it maintained an uncompromising stance towards the Palestinians.”

Never mind that at that time, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), and especially the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), were still very much wedded to terrorism and refused to recognise Israel’s right to exist.

In 1979, he was appointed as First Secretary in the Damascus Embassy, writing that his work was “mostly liaison with the Syria-based… members of the Palestine Liberation Organization” and hosting “dinner parties” where US officials could circumvent legislation preventing them meeting with PLO members.

In December 1979, Bowker led the first meeting of Australian officials with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat and was left unimpressed – assessing Arafat as “primarily a politician, and a facile interlocutor, rather than a strategist.”

He was more taken by “other Palestinian contacts and friends” through whom “I developed substantial sympathy for the Palestinian cause vis-à-vis Israel.”

This sympathy extended to Bowker “develop[ing] a sceptical view of the 1978 Camp David Accords and subsequent peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, at least so far as [they] impacted on the prospects for achieving a durable peace with the Palestinians.” His opposition to the Accords included crossing swords via classified cables with Australia’s ambassador in Tel Aviv David Goss, who supported the Accords.

Bowker does say he was less than impressed by “Syrian officials, who were unfailingly polite, sophisticated interlocutors” but failed to acknowledge their own “contribution to the circumstances under which [Israel’s] occupation [of the Golan Heights] had arisen.”

A chapter dedicated to his stint as Ambassador to Jordan between 1989 and 1992 recounts that Jordanians were rather sheepish about having believed Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s empty promises to “force Israel’s hand in regard to the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.”

Returning to Australia just as the Oslo peace process began, Bowker undertook a year’s paid leave to write an MA Thesis at the Australian National University’s newly formed Centre for Middle East and Central Asian Studies under Amin Saikal, which later became the basis of Bowker’s 1996 book Beyond Peace: The Search for Security in the Middle East.

Despite his reservations over whether Oslo would give Palestinians a “measure of justice”, Bowker does rightly point to one key problem – to make progress in peacemaking requires convincing Palestinians to normalise relations with Israelis, and he admits this has proven very difficult.

In 1995 he was appointed to head the Middle East and North Africa section (MENA) at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, but not before, he alleges, there were objections from local pro-Israel leaders, which he attributes to the fact that in 1987-88 “I had been prepared to push back against the advice offered by certain Australian officials who I felt were promoting unduly sympathetic interpretations of Israeli policy towards the Palestinians.”

Bowker’s personal devotion to the Palestinian cause is further revealed in his self-described “shouting match” with Michael Thawley, the international policy adviser to then newly-elected Prime Minister John Howard, at a Zionist Federation of Australia/United Israel Appeal dinner in 1996.

The Howard Government wanted to dilute the language of Australian support for Palestinians to have their own “independent state” to something more ambiguous, which infuriated Bowker.

Whilst Bowker acknowledges governments have the right to set policy, he asserts they compromise too easily over Israeli-Palestinian issues due to electoral considerations and the influence of the pro-Israel lobby.

The story concludes with a telling incident demonstrating how deeply emotionally involved in the Palestinian cause he is. Bowker writes that when he attended a luncheon given by the Australia/Israel Chamber of Commerce in 2000 at the same venue, “the events of that night [at the 1996 dinner] came flooding back, and I suffered an attack of post-traumatic stress disorder which needed to be addressed with the assistance of the Departmental Counsellor.”

In 1997-98, Bowker moved to Gaza to work for the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) that provides medical and education services to Palestinian refugees in the Middle East – but also uses an unprecedented and ridiculous definition of such refugees and effectively promotes a Palestinian “right of return” that is completely incompatible with a two-state peace.

His account of the agency is illuminating. Writing on the politics of Palestinian refugee status and the theatrics involved in fundraising, he notes that “dwellings that needed refurbishment” are called “shelters” to avoid any suggestion of “permanency which was not politically acceptable to the refugees.”

Potential donors were shown Gaza homes that were “devoid of items such as satellite television dishes that might detract from the imagery required. All visitors had to step over at least one open drain.” To his credit, Bowker’s efforts to call attention to problematic fundraising-oriented policies at UNRWA led to him being effectively pushed out of the organisation.

His disappointment at Arafat’s “utter failure” to “exercise leadership” by promoting the two-state solution are also to his credit.

Yet Bowker’s recollections are compromised by such factual lapses as claiming that Shimon Peres lost the 1996 election to Binyamin Netanyahu because “Arab Israelis… largely chose not to vote” to protest Israel shelling the Lebanese village of Qana in April 1996. In reality, Peres’ 20 point lead over Netanyahu evaporated after a series of Palestinian suicide bombings that killed 59 Israelis in the weeks before the poll.

In Chapter 17, Bowker expounds upon his highly problematic thesis that the two-state solution is dead (see Bowker’s letter on the subject published in last month’s AIR and our response) and therefore that there must ultimately be a “one-state solution” that “treats Israelis and Palestinians as equals.”

His claim the Oslo process “degenerated” because “Israelis lost interest” fails to properly acknowledge the detail in the 2000, 2001 and 2008 offers that provided a realistic horizon for Palestinian aspirations, including for Jerusalem and its holy sites, as well as the withdrawal from Gaza and its aftermath. His figures claiming Palestinians outnumber Jews in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza combined and that they also have more children are just plain wrong.

There are many more assertions that will frustrate the informed pro-Israel reader and paint Bowker as being on autopilot, happy to regurgitate inaccurate or questionable pro-Palestinian talking points that he imbibed during his salad days in the Middle East in the 1970s and 80s.

Overall, despite Bowker’s attempt to portray himself as an even handed expert on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, his knowledge about Israel clearly relies on refracting it through the prism of what he has heard from Arab and Palestinian sources. The book contains little evidence of any close relationships or friendships with Israelis.

As a memoir of Australia diplomatic service over several decades, including some first-hand insights into historical events and realities, this book has value. Politically, however it is also largely an example of how outmoded and one-sided Arabist thinking developed in the 1970s and 80s impedes clear analysis of contemporary Mideast realities today.

Tags: Australia, Israel, Middle East