Australia/Israel Review

Asia Watch: Another kingpin down

Jun 30, 2021 | Michael Shannon

Security forces in Southeast Asia retain an impressive capability to pick-off or jail leaders of jihadist groups, but emptying the well from which they emerge remains a more difficult challenge.

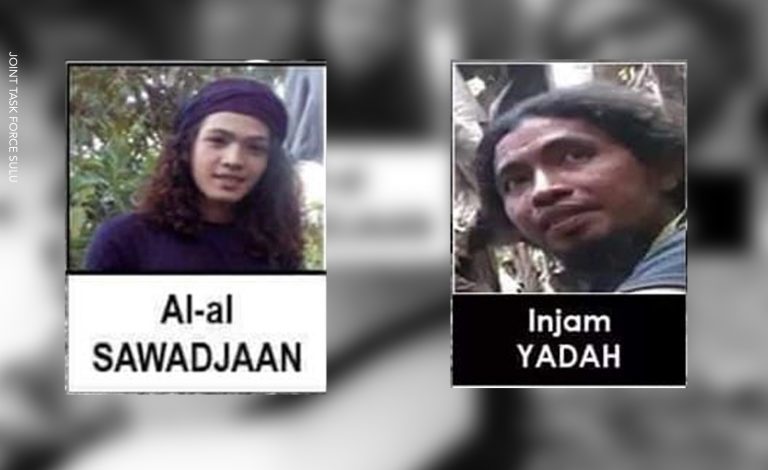

A nephew of the Islamic State (IS) leader in the Philippines and an Abu Sayyaf commander accused of beheadings were among four militants killed by security forces in a dawn raid on June 13 in the southern Sulu islands.

Among those killed was Al-Al Sawadjaan, a suspected bomb maker and the youngest brother of Mundi Sawadjaan, the Philippines military told local media. Both men are nephews of the Abu Sayyaf commander and IS leader in the Philippines Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan.

The Sawadjaans have been blamed for orchestrating bomb attacks in Jolo, Sulu’s main city, including a bombing in August 2020 that left 14 dead and an attack by two Indonesian suicide bombers at Jolo’s cathedral in January 2019 that killed 23 people.

The prized scalp claimed in the raid was Injam Yadah, an Abu Sayyaf militant notorious for a string of high profile abductions and beheadings. Yadah was accused of being involved in snatching eight Indonesian fishermen in waters off Malaysia in January 2020. Three were immediately released, one was executed in October 2020 and four were rescued by Filipino troops in March 2021. He was also linked to the kidnapping in 2015 of two Canadian tourists who were later beheaded after a ransom payment deadline passed.

The Abu Sayyaf is now believed to number about 200 militants, operating largely out of Sulu and the nearby island of Basilan. Although it is believed to be split into two factions, it remains under the nominal leadership of Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan, who has not been heard from since last year.

There is speculation that Hatib died in a clash with the military, but his body has never been found, which raises questions about the apparent leadership void of IS-aligned groups in the region.

The killing of five Abu Sayyaf fighters in a shootout in the Malaysian state of Sabah in May points to a group under pressure – dispersing into small units, even crossing into foreign jurisdictions to evade the Philippines military. The gunfight in Beaufort, a district in western Sabah, occurred more than a week after police arrested eight Abu Sayyaf suspects and 29 others from the same area after a tip-off from Philippine authorities.

The Malaysian police operations illustrate the crucial role that cross-border and inter-agency intelligence sharing play in countering the activities of militant groups. In 2017, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia launched trilateral patrols aimed at preventing acts of piracy and kidnappings at sea along their common maritime boundaries.

Meanwhile, the Indonesian Government’s drive to limit the influence of Islamist radicalism risks negative implications for democratic governance, argues a new report from the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC).

The report examines the trajectory of the campaign against extremism from its origins as a reaction to the mass mobilisation in 2016, which brought down the then Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (AKA “Ahok”) on spurious blasphemy charges, to the current drive against the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), an Islamist vigilante group.

The downfall of Ahok, a protégé of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, galvanised the President’s view that extremist Islamist groups had to be reined in. The banning of FPI and Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia, the largest and most visible of such groups, headlined a series of moves to deny “radical”, anti-democratic ideologies access to state institutions.

The IPAC report argues that the definition of radical is “overly broad” and could potentially include any government critics, with no appeal mechanism for those identified. The report also questions the involvement of the military in some aspects of the campaign, arguing it could signal a return to a more political role.

The downfall of the FPI has been striking. Once afforded a large measure of police and military protection for its vigilante-style attacks on “vice”, its excesses have prompted an increasingly hardline response from the Widodo Government.

Its firebrand Islamic cleric leader, Habib Rizieq, was sentenced in May to eight months in prison for encouraging people to attend mass gatherings in violation of COVID-19 protocols. Rizieq returned to Indonesia in November from self-imposed exile in Saudi Arabia, pledging to lead a “moral revolution”, with the aim of consolidating hardline Islamic groups against the Widodo Government.

An estimated 50,000 supporters swamped him at Jakarta airport, while two other large gatherings brought things to a head. A clash in December between FPI members and police left six of Rizieq’s bodyguards dead, and Rizieq’s arrest followed soon after. By February, the FPI had been formally banned and most of the group’s top leadership was behind bars.

Tags: Asia, Indonesia, Islamic Extremism, Philippines