Australia/Israel Review

Israel and Turkey – a new battleground?

Jan 29, 2025 | Alana Schetzer

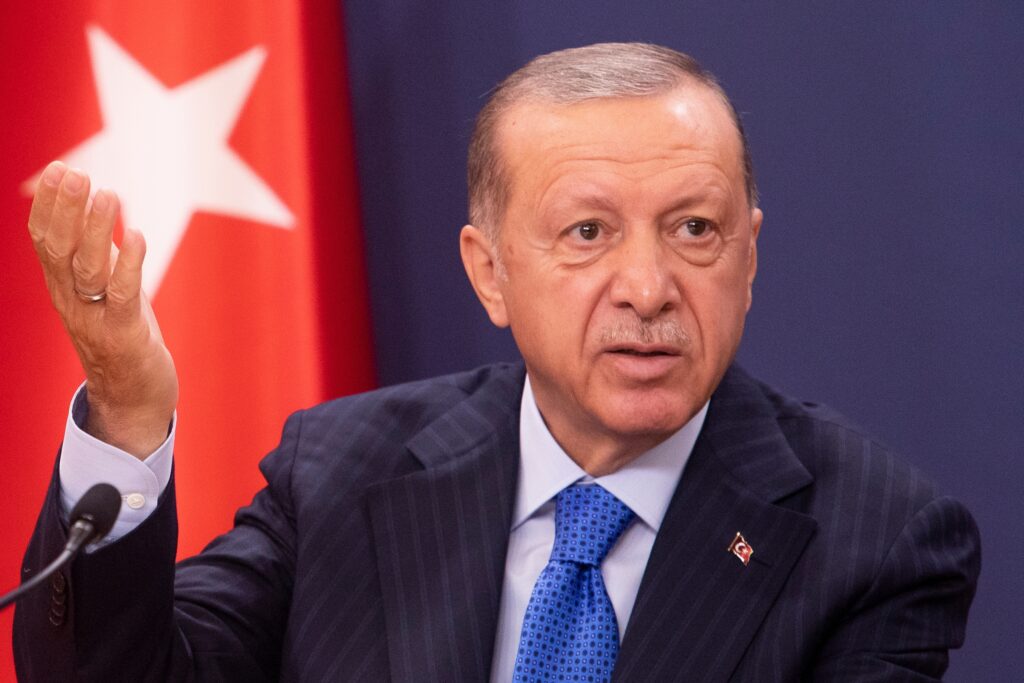

For decades, Turkey and Israel had amicable – sometimes even warm – diplomatic, political and economic ties. But since Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – who has been in power for 22 years – turned Ankara away from Europe and the United States during the early 2010s, that relationship has been cooling radically. Since late last year, Turkey has no diplomatic relations with Israel and embargoes all trade with the Jewish state.

Turkey’s position in the Middle East has also changed dramatically over the past decade and a half. Ankara has been making strategic decisions – politically and militarily – designed to spread Turkish influence and power across the region, as well as in Africa.

Following the October 7 terror attacks, Erdogan’s anti-Israel rhetoric escalated to new heights; Turkey was the only NATO member to support Hamas during the current war, repeatedly hosting Hamas leaders and increasing both logistical and diplomatic support for the terrorist organisation. There is even evidence that Ankara helped smuggle weapons and explosives to Hamas terror operatives in the West Bank, and allowed Hamas to orchestrate terror attacks against Israel from Turkey.

Bizarrely, Erdogan accused Israel of intending to invade Turkey and start a war last year, claiming that Israel wanted to capture Anatolia (which makes up the majority of Turkey’s land mass) in order to create “Greater Israel” – antisemitic conspiratorial claims that experts describe as “not rooted in reality.” The claim was even met with backlash from within Erdogan’s own party.

This odd claim was likely part of Erdogan’s well-practised “neo-Ottoman” rhetoric designed to stir up ultranationalism at home. He’s done this before, arguing that Turkey should have taken the Iraqi city of Mosul, whilst continuing to emphasise Ankara’s long-standing dispute with Greece regarding islands in the Aegean Sea.

In a speech several years ago, Erdogan named himself among the greatest of all Turkish rulers, including Osman Ghazi, founder of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century.

In July 2024, Erdogan threatened war against Israel in direct response to its conflict with Hamas in Gaza. “[We] must be very strong so that Israel can’t do these ridiculous things to Palestine,” Erdogan said. “Just like we entered Karabakh [the disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan], just like we entered Libya, we will do [something] similar exactly to them.”

Since then, a new nexus has been added to the threat of physical confrontation between Israel and Turkey – Syria. Following the overthrow of the Assad regime on Dec. 8 last year, Turkey supplanted Teheran as the major foreign power and dominating influence there. It has long backed the formerly Al-Qaeda-affiliated group Hayat Tahrir a-Sham (HTS), which toppled the Assad regime. Turkey has also long occupied northern Syria as part of its policy of trying to subdue Kurdish militias in the region.

There is speculation that Erdogan could even turn Syria into Turkey’s own satellite state, which would be of great concern to Israel. Meanwhile, HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Muhammad al-Julani), while currently trying to dampen international concern over his new regime, has spoken multiple times in the past of attacking and conquering Israel as part of his jihadist ideology.

In January 2025, the Israeli Government’s Nagel Commission released a report stating that the IDF needs to rebuild and prepare for possible conflict with Turkey, probably in Syria. It also highlighted wider regional instability and possible changes, such as the prospect of Jordan’s monarchy being destabilised.

The report states, “The problem will escalate if Syrian forces effectively become a ‘Turkish proxy,’ as part of Turkey’s ambition to restore Ottoman-era influence. The presence of Turkish forces or their proxies in Syria could heighten the risk of a direct Israel-Turkey confrontation.”

David Tittensor, Senior Lecturer in Islamic Studies at the University of Melbourne, says the chances of Erdogan acting on his war threats or direct Israel-Turkey military clashes erupting are “probably unlikely. It might just be rhetoric for domestic consumption.”

However, Dr Michael Rubin, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a specialist in Iran and Turkey, is more alarmed.

“The longer the West and Jerusalem remain in denial about Erdogan and the changes wrought by two decades of ‘Erdoganism’, the more likely [direct conflict] becomes. Remember, Iran was once an ally of Israel as well and Western leaders believed Ayatollah Khomeini’s [initial] rhetoric about peace and tolerance. That Turkey now has its own nuclear program and has a major indigenous military industry reflects a major threat,” Rubin explains. “So too does the fact that the biggest difference between Iran and Turkey is that Turkey can hide behind NATO while it prepares for any offence.”

Rubin compares Turkey’s relationship with HTS to that of Iran’s relationship with Hezbollah.

“Turkey is to Hayat Tahrir a-Sham what Iran is to Hezbollah. Ankara – or, rather, the Turkish intelligence service – calls the shots. That said, what the West isn’t talking enough about is how Ahmed a-Sharaa’s charm offensive is motivated less by sincere reform and more to gain early recognition so that international reconstruction aid gets channelled through him. Erdogan underwrote Hayat Tahrir a-Sham and now wants payback in terms of construction contracts,” Rubin says.

In mid-January 2025, Erdogan threatened Israel with “unfavourable outcomes for everyone” if the IDF didn’t withdraw its troops from a buffer zone in Syria it took over soon after the fall of al-Assad as a temporary defensive measure. Erdogan said this even as he himself threatened further Turkish military action across Syria, beyond the northern regions that Turkey has controlled since 2016.

Of course, despite Ankara and Jerusalem being at loggerheads in an unprecedented way, they do have some things in common, such as a shared interest in keeping Iran out of Syria. Given the state of their relationship, would this be enough for them to work together, at least in limited ways?

Rubin says no. “Israel understands Iran is an existential threat. Turkey’s problem with Iran is not that Iran poses a threat to it, but rather that Turkey is jealous and wants to replace Iran as the centre point of Islamic resistance,” he says.

Gallia Lindenstrauss, Senior Researcher at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, adds that both countries have a “significantly different approach to their relationship with Iran.”

“Iran denies Israel’s right to exist, resulting in a relationship that is entirely negative. In contrast, Turkey and Iran maintain diplomatic relations and have numerous opportunities for dialogue.”

While Ankara wants to continue to nullify Teheran’s influence in Syria, it apparently continues to work with the Iranian regime when it comes to Lebanon. It has been reported that Ankara is allowing Teheran to use its airspace to resupply and rearm Hezbollah, which would be a major problem for Israel.

There have been some brief periods of temporary reprieve from the ever-building tension in the Turkey-Israel relationship, including in June 2022, when then-Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid thanked Turkey’s intelligence agency MIT for working with Mossad to help foil an Iranian plot to kill Israeli tourists on Turkish soil.

However, there are also fears that Ankara’s current hostile approach toward Israel, severe as it is, could worsen further. For example, Turkey could choose not to allow the passage of oil coming from Azerbaijan destined for Israel through its territory – a move that hasn’t been implemented so far, despite the Turkish trade boycott.

Lindenstrauss says as Turkey’s regional power increases, Israel must adapt to the new political landscape. “Israel needs to learn how to operate vis-à-vis the new actors in power in Syria and their backers,” she says. “However, there are many unknowns regarding Syria’s future, and some level of dialogue with Turkey will be necessary to address potential developments.”

Lindenstrauss adds that the Gaza ceasefire and Donald Trump’s presidency could potentially improve Ankara and Jerusalem’s relationship, despite the many barriers between them.

“Such a ceasefire might lead Turkey to lift the complete trade ban it imposed on Israel [in May 2024], thereby repairing some of the personal and business-to-business relations that have been negatively affected by the trade ban. Additionally, the entrance of President Trump into office may assist both sides in lowering the level of tension between them.”