Australia/Israel Review

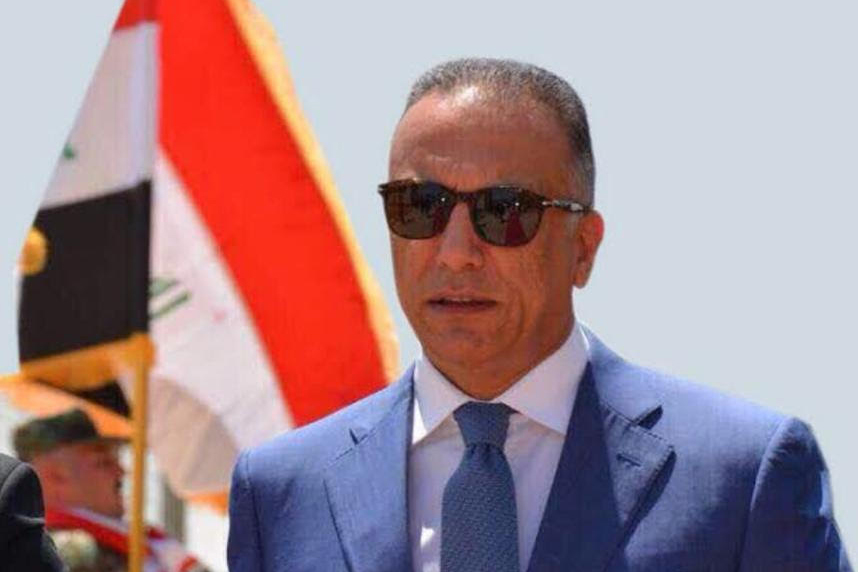

The Harrowing of Mustafa Kadhimi

Nov 25, 2021 | Michael Knights

In Old English, the word “harrowing” suggests a test of fortitude, of suffering through a trial, of being tempted and tormented. In Christianity, Christ goes through a harrowing after his death as he walks through Hell on his way to resurrection.

Iraq’s premier Mustafa al-Kadhimi certainly makes no pretensions to be anything more than a man trying his best, but he too is being harrowed as Iraq passes through its customary trial of elections, horse-trading, and government formation. In the latest twist of this long and winding tale, bombs dropped by drones struck Kadhimi’s house in the early hours of Nov. 7, likely meant to intimidate politicians of all stripes, though thankfully leaving the premier himself unharmed.

This is not the first time that militias have targeted Kadhimi and those close to him. Kadhimi’s first physical confrontation with Iran-backed militias came during the previous government formation process in April 2020, when nearly 100 armed militiamen from the Iran-supported terrorist group Kataib Hezbollah (KH) surrounded Kadhimi and his security detail at the Prime Minister’s Guesthouse, a kind of hotel for government officials and visitors. At the time, Kadhimi’s position was head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service (INIS).

Though well-protected, his men were no match for 100 militiamen, some carrying rocket-propelled grenades designed to blow up armoured vehicles and bunkers. There had been an altercation between Kadhimi’s guards and KH fighters some days earlier. Then, KH took the opportunity to seize a bodyguard, rough him up, and throw him in jail – sending a message to the man who many expected would become the next Prime Minister. The intimidation did not work: Kadhimi did become premier, even after KH’s Hossein Moanes (Abu Ali al-Askari) warned that his appointment would be considered an act of war and would “burn what remained of the stability of Iraq.”

Fast forward to June 2020, with Kadhimi ensconced as prime minister but still living in the same villa by the Tigris River, owned by a famous writer and friend of Kadhimi’s. When Kadhimi ordered the arrest of a KH terrorist, the militia sent another convoy of armed trucks to his house. They parked a twin-barrelled anti-aircraft gun outside as they “negotiated” for the prisoner’s release. Unknown to most Iraqis, Kadhimi still did not release the KH member after this effort at intimidation. Instead, the militiaman was set free only months later, released by a cowed judiciary. Just weeks into his premiership, receiving shaky signals from his own military commanders, Kadhimi was not ready to risk full-scale war with the militias.

Kadhimi is now better protected than he was then. His security measures and international backup are designed precisely to deter or defeat the small army of militia forces available to attack him. This is why the militias sent drones against his house instead. Many people have expressed shock over the drone attack, but it is not even the first time that Kadhimi’s house has been attacked by drones. On March 4, 2021, militias correctly sensed the beginning of pre-electoral negotiations to sideline them after the upcoming Oct. 10 elections. They responded by flying unarmed drones at the houses of key political leaders, Kadhimi included. A quadcopter struck his house, a forewarning of the Nov. 7 attack.

As the earlier attacks on Kadhimi’s security detail in April 2020 showed, militias are as interested in hurting Kadhimi’s friends and colleagues as they are in hurting the Prime Minister himself. The Iraqi National Intelligence Service (INIS) is Iraq’s premier intelligence agency, responsible for countless arrests of Islamic State terrorists and other criminals. Yet the Iran-backed militias hunt it for sport in an effort to undermine Kadhimi and the system he has established to protect journalists, protestors, and citizens from militia attacks.

Civilians close to Kadhimi have been kidnapped, tortured, and sometimes killed. His network is included in the broad swath of Iraqi people targeted by militias. Kadhimi’s affiliates are on the front lines of these attacks, and live with this daily fear.

Kadhimi’s step-by-step pushback against the militias is a frustratingly slow-burn strategy: one replacement of a compromised officer, one terrorism arrest, and one anti-corruption case at a time. But the arrests are building up, and the court cases are bearing fruit.

Such work takes time, and Iraqis are rightfully impatient. Yet while any Iraqi prime minister can easily become a dictator and a death squad commander, Kadhimi does not want rivers of blood in Baghdad if steadily chipping away can reduce the risk to ordinary people. This is why Iraq’s security forces arrest militiamen instead of summarily executing them, even though they may later be released due to corruption and intimidation. Rule of law does still matter to some in Iraq, and they continue to believe they can win through it rather than by going beyond it. Kadhimi is one of the Iraqis who continues to advocate for the rule of law, and the international community should recognise how rare it is to find a leader who chooses not to unleash brutality when he is under intense pressure to do so.

It is also quite fitting that this time, the Iran-backed militias bombed the front steps of Kadhimi’s modest house by the Tigris. It was on those exact steps that Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, stood to offer Kadhimi the premiership in 2018, were he to agree to bend the knee to Teheran and serve as its premier in Iraq. When he declined, it chose Adel Abdulmahdi instead, with his ruinous era of premiership lasting just two years. Kadhimi did become premier afterwards, but not by Iran’s hand, and despite the death threats of Iran and its militias.

Now, as Iraq forms a new government after the recent elections, the same militias have laid down a red line that the next premier can be anyone except Kadhimi. That should tell us something.

As Iraqi writers Hamzeh Hadad and Muhammad Al-Waeli noted in a 2018 piece, Iraq needs a leader with vision if the country is to recover. But I would argue it also needs a quietly brave leader with a conscience and a sense of responsibility. Watching Iraq nose-dive under Abdulmahdi and begin to recover under Kadhimi has driven home the importance of the identity and character of Iraq’s prime minister. In such a centralised system, a good premier is necessary, though not sufficient, to keep Iraq on the right path.

Appointing such a leader is the vital first step that makes positive change possible. Whether Kadhimi becomes Prime Minister again or not, the militia’s efforts to tempt and torment him, and to drive him off his course, suggest he has done something right in these last two years, and that his example of staying the course against the militias should be emulated by future premiers, and supported by Iraq’s friends.

Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, specialising in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. © Washington Institute, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iran, Iraq, Islamic Extremism