Australia/Israel Review

Viewing Israel on Arab TV

Jun 2, 2020 | Ran Porat

During Islam’s holiest month of Ramadan (April 23 – May 23 in 2020) billions of Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset and then break the fast with a traditional Iftar dinner. Observing Ramadan is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, and believers use the month to pray in mosques, reflect on their lives and engage with their communities.

Arab TV stations prepare special Ramadan drama series to broadcast every night after the fast ends. These programs receive very high ratings (30% higher than normal), and this year viewership is most likely even higher, given the lockdowns across the Arab world as states deal with the coronavirus pandemic.

Ramadan TV series often stir controversy when engaging with contemporary issues, such as selfies, women’s rights or ethnic tensions. Renowned Arab actors line up to participate in these shows, with scripts that may present new versions of historical stories, Hollywood movies or famous plays, and which are often saturated with soap-opera style plot convolutions.

However, Ramadan TV series are not purely for entertainment. In many respects, they reflect the issues and messages that the authoritarian regimes in the Arab world want to convey to the public. The scripts for these shows are subject to intense government scrutiny and heavily censored.

Some of this year’s Ramadan TV series exploded into controversy because they dared to touch on one of the most sensitive topics in Arab politics – normalisation of ties, open and hidden, with Israel.

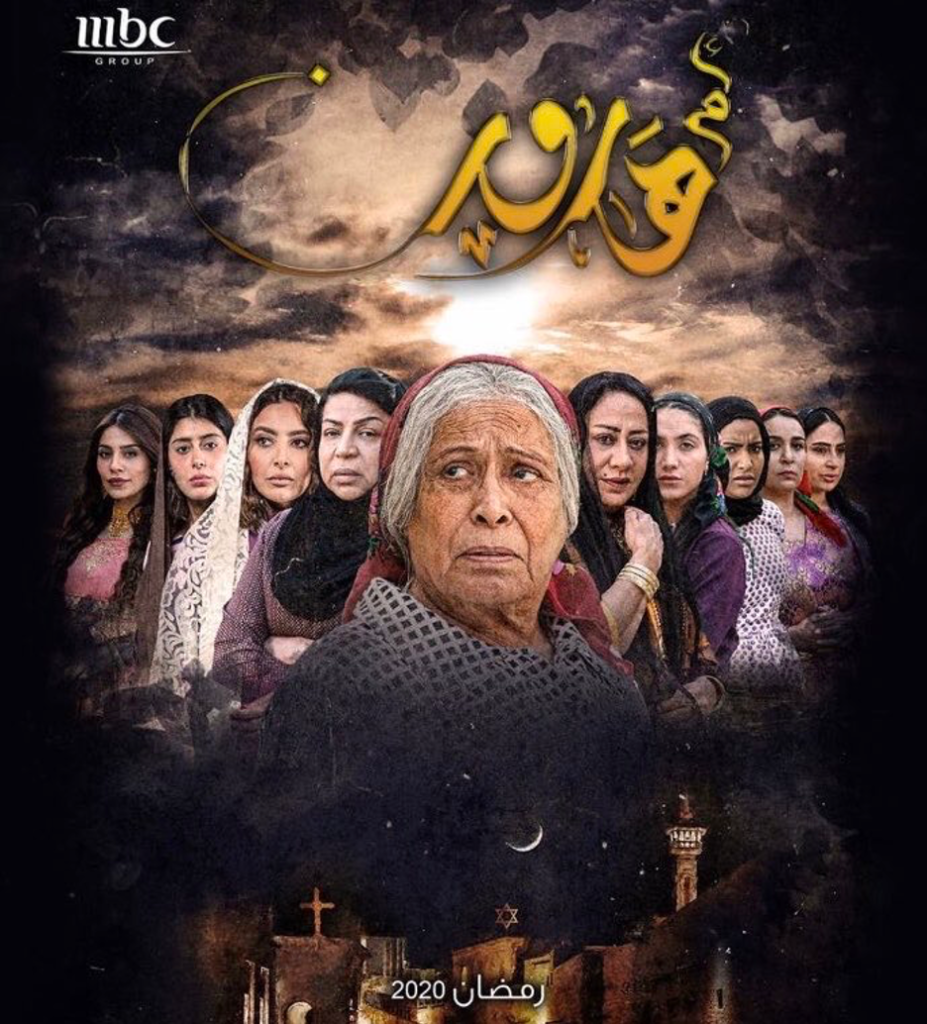

“Um Haron” – official poster for the series

“Um Haron”

“Um Haron” (Aaron’s mother) is the most talked-about 2020 Ramadan series. It is a joint production of several Gulf states, shot in the UAE and in Kuwait and broadcast on MBC, a Saudi TV satellite channel.

It tells the story of a Jewish family in Kuwait in the 1940s and is based on a real person, Bahraini Jewish nurse Um John. The matriarch and Jewish midwife Um Haron (portrayed by Kuwaiti superstar Khayat al-Fahed) and her children face discrimination, which turns into persecution after the creation of the State of Israel in 1948.

The proclamation of Israel as a state takes place in a scene of a marriage between a Jewish woman Rahil and Muslim man Mohammad (this is permitted in Islam but forbidden if the women is Muslim and the man is Jewish). Later, one of the Jews is murdered and the family flees to Israel.

“Um Haron” immediately drew criticism. Critics picked up on historical inaccuracies in the script, as well as some gross mistakes in the spoken Hebrew used (grammatical mistakes, words in English instead of Hebrew), and also in written Hebrew words written from left to right, instead of right to left, depicted on props used in the show.

“Um Haron” revived the story of the forced exodus of approximately one million Jews from Arab states during the 1940s, 50s and 60s. This topic was considered taboo in the Arab world until recently, and was largely erased from public records and schoolbooks. Arab states did not want to be seen to be supporting Israel’s existence by allowing knowledge about these Jewish refugees to serve as a counter-narrative to the Palestinian “Right of Return”, or Nakba story, which centres around the suffering of refugees created by the “Zionist entity” during the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. Arab leaders also would have wanted to avoid any comparison between the relative success of Israel in absorbing Jewish refugees from Arab states, and the perpetual refugee status, and the accompanying poverty and discrimination, experienced by Palestinians in Arab states.

To Western eyes, the series also portrays the Gulf states as religiously tolerant, in contrast to perceptions of Muslim extremism. Actors and creators of “Um Haron” emphasised that the focus of the series is tolerance towards minorities, not Zionism.

Underpinning the heated debate surrounding “Um Haron” are the increasing covert and open ties between Gulf states, headed by Saudi Arabia, and Israel, in light of their shared enemy, Iran and its proxies. Opponents of the series are arguing it is yet another stage in the process of preparing the Arab public opinion for normalisation of relations with Israel.

Arab columnists in the anti-Saudi camp, mostly from Lebanon, Syria and Hamas in Gaza, used the series to attack Riyadh for what they see as a systematic marginalisation of the Palestinian issue, starting from the Saudi peace initiative of 2002, and leading up to Saudi willingness to engage with the US Trump Administration’s Israeli-Palestinian peace deal presented earlier this year.

Several Kuwaiti parliamentarians demanded that an official commission of inquiry be set up to investigate why the series was allowed to be filmed and broadcast. Despite this, MBC refused to stop broadcasting the series, and attacked other networks (a dig directed largely at the Qatari channel Al-Jazeera) for hosting Israeli officials on their programs.

Meanwhile, social media has been boiling over with insults and verbal combat between Palestinians and Saudis over the series. Palestinians circulated their own satirical version of a poster for the series, with the face of former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon replacing the face of the main character and changing the name of the series to “Um Sharon”. They accuse the Saudis and other Gulf states of using “Um Haron” as “a mobilised form of art” aimed at maximising profits from their connections in Washington and legitimising closer ties with the Jewish state.

After being ridiculed as “primitive camel people from the desert” by Palestinians, and with pro-Hamas twitter feeds calling normalisation “the real corona”, online Saudis fired back, accusing the Palestinians of being “traitors and ingrates”, usurping billions of Saudi dollars given to them over the years.

This is not the first time Jewish persecution in Arab states was at the centre of a Ramadan series. The 2015 Egyptian series “Kharat al-Yahud” (“The Jewish quarter”) followed a similar storyline and also caused backlash. It described the flourishing Jewish community in Egypt and included a romance between a Muslim policeman and a Jewish girl. Again, with the creation of the State of Israel everything goes pear-shaped and the Jews are forced to flee. The plot was groundbreaking because it acknowledged for the first time the deportation of Egyptian Jews. The Islamists in Egypt warned that “Kharat al-Yahud” was a mechanism by the relatively new government of pro-Western President Abdel-Fateh el-Sissi to justify peace with Israel and present the damage Muslim Brotherhood terrorists inflict on Egypt.

“Exit 7”

“Makhraj 7” (Exit 7)

The satirical Saudi show “Makhraj 7” (“Exit 7”) also aired on MBC. It was written by liberal journalist Khalal al-Kharbi and stars the famous actor, Nasser Al-Qasbi. Mostly focused on internal Saudi affairs, in one episode a Saudi family is rocked by the discovery that one of their children is connecting with an Israeli child during an online gaming session.

In one of the scenes, a person who has business ties with Israel – played by Rashed Al-Shamrani – states that “the enemy is [not Israel, but rather] the side who does not value the fact that you stand with him, cursing you day and night more than the Israelis.” He then adds: “We have engaged in wars for Palestine. We cut off the oil for Palestine. When Palestine came to the rank of authority, we started to pay salaries when they needed them. As for the Palestinians, they do not hesitate to attack Saudi Arabia whenever they have the opportunity.”

In other segments of the scene, characters say: “Like it or not, Israel exists”; “Israelis are human beings like you” and even, “the Arabs have only lost the Palestinian cause over the years. So many words for nothing!”

Facing heated criticism, the creators of the show were quick to clarify that they oppose normalisation with Israel. Yet some Saudis online praised the words put in Al-Shamrani’s mouth as “truths finally coming out” and supported ties with Israel. Many believe that there is an undercurrent in the Gulf states of those who are frustrated over what they see as Palestinian ingratitude despite decades of financial and diplomatic backing by the Gulf states.

On the other side – “The End”, “The Guardian of Jerusalem” and “The Ink of Fire”

“The End”

Egypt is considered the capital of Ramadan TV series productions. This year’s sci-fi drama “El-Nehaya” (“The End”) broadcast on the private ON TV network, is a dystopia about a world governed by technology.

In a scene in the opening episode that has caught the attention of viewers, the main character explains to young students from a class in the distant future what supposedly happens a century from now – Arab countries take advantage of the fall of the United States, which has split into separate states, and launch “The free Al-Quds [Jerusalem]” war against Israel. The Arabs win and destroy Israel, and most Israelis emigrate to Europe.

This scene went viral on Arab social media and received positive reactions, including from media outlets affiliated with the Egyptian Government. Israel’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement protesting the “regrettable and unacceptable” content of the series.

Later in the series, the “achievement” of conquering Jerusalem becomes a liability, as technology takes over from humans. Some commentators saw this plot twist as a message to Arabs that removing Israel will not solve all their problems.

“Guardian of Jerusalem”

The anti-Western camp in the Arab world has also produced Ramadan TV series. Syrian state TV and Hezbollah’s Al-Mayadeen channel screened “The Guardian of Jerusalem”, about the life of Syrian titular Archbishop of Caesarea in the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, Hilarion Capucci, who also served in Jerusalem. He was arrested by Israel in 1974 for aiding Palestinian Liberation Organisation terror attacks and was released in 1978 under a deal struck between Israel and the Vatican.

Hamas TV is airing “The Ink of Fire” series which hails armed struggle against “cruel” Israel.

Meanwhile, a song in Hebrew briefly played in the background during a disco scene in the first episode of Syrian Ramadan series “The Magician” led Damascus to order the TV channel not to show that segment again.

Ramadan television this year reflects the deep rift between the belligerent camps in the Arab world. These drama shows provide both hope for changing regional attitudes and signs the old guard is not about to surrender its cultural dominance meekly.

Dr Ran Porat is a researcher at the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation at Monash University; a research fellow at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism at the Interdisciplinary Centre in Herzliya, Israel and a research associate at the Future Directions International Research Institute, Western Australia.

Tags: Israel, Jews, Media/ Academia, Middle East