Australia/Israel Review

Justice Delayed

Jul 30, 2019 | American Jewish Committee

Around the world, sombre commemorations marked the 25th anniversary of the bombing of the Argentine Israeli Mutual Association building, or AMIA Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires on July 18, 1994 – the deadliest antisemitic attack since the Holocaust.

In Buenos Aires, the President has signed a decree that adds Hezbollah to a registry of terrorist organisations. In addition, Pope Francis sent a letter to the Jewish community, 200 artists chanted a musical kaddish on stage at Buenos Aires’ iconic Colon Opera House, and thousands of people flooded the street in front of the rebuilt AMIA building as they do every year in an expression of solidarity.

But survivors say the most meaningful tribute would be the prosecution of those responsible and a full reckoning for the nation’s failure to hold anyone accountable. An official investigation found that Iran was behind the attack and that the suicide bomber who drove the explosive-laden truck into the six-storey AMIA building was a member of Iran’s proxy, Hezbollah. Meanwhile the only people convicted in connection with the bombing have been Argentine officials who conspired to cover it up.

To commemorate the tragic event’s 25th anniversary, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) looks back at events of the last quarter century, as told by AJC CEO David Harris, AJC Chief Policy and Political Affairs Officer Jason Isaacson, Director of AJC’s Arthur and Rochelle Belfer Institute for Latino and Latin American Affairs Dina Siegel Vann, and longtime AMIA employees Anita Weinstein and Daniel Pomerantz, who both miraculously survived the deadly blast and still work there today.

Daniel Pomerantz, who held an accounting position at AMIA in 1994, was still marvelling at Brazil’s fourth World Cup championship win the previous day. When a colleague from human resources called to discuss something work-related, he offered to go to his office. That decision saved his life. He was still there at 9:53am, when the bomb struck his office and levelled much of the AMIA building.

DP: “He asked me a question, I answered and started to walk away. He insisted I stay just one more second to discuss. Fortunately, I survived this discussion. My office was destroyed.”

Anita Weinstein, director of documentation and the information centre for AMIA, worked in a separate building just a couple of blocks away. But in 1994, she was also assigned to help organise AMIA’s centennial celebration. Around 9:30am, she walked down the street, entered the main building, and went up to the second floor to see a colleague whose office was toward the rear of the building.

AW: “That made a great difference. As soon as I arrived there the explosion happened. Everything started to shake. We could not breathe. We could not see very well. Those moments, those minutes, that time was terrible.”

Weinstein climbed to an adjacent roof. From there, she looked down and saw the unforgettable scene of destruction, reminiscent of the bombing of the Israeli embassy just two years earlier that killed 29 people.

AW: “That was the first moment we could see the terrible shape of the building, the debris still falling, the horrible moment when we understood that there had been a bombing again.”

David Harris, AJC’s CEO, recalls hearing news of the attack in his New York office. Terrorist attacks, which at the time were increasingly targeted at Israelis, were sadly becoming routine. But as the scope of the atrocity became known, it was clear that this attack was like no other.

Harris tapped Jason Isaacson and Jacob Kovadloff, then AJC Director of Latin American Affairs, to go straightaway to Buenos Aires. Nearly 17 years earlier, Kovadloff, an Argentine national, had worked for AJC on the ground in Buenos Aires before fleeing the death squads of the military junta.

Isaacson recalls seeing family members gathered on the steps of the Chagall Cultural Centre in Buenos Aires, their eyelids swollen, their stares blank, waiting to hear if their loved ones survived.

JI: “This was the worst attack against Jews that had ever happened in the Americas. It was overwhelming. The city was really shaken. The community was shaken. The country was shaken.”

He recalls President Carlos Menem weeping on national television and the 200,000 Argentines who filled the downtown Plaza de los Dos Congresos for hours in the freezing rain to sing Argentina’s and Israel’s national anthems, recite the mourner’s kaddish, and demand justice.

Government offices had been closed by decree and the trade union federation had called on members to stop work and attend the rally. Banners in Spanish proclaimed: “No to violence,” “Standing up against terror demands that justice is done,” and “Today we are all Jews.”

JI: “In private meetings with AJC, Interior Minister Carlos Ruckauff and Foreign Minister Guido Di Tella were firm in their resolve to trace the source of anti-Jewish terror to its roots – whether in Hezbollah or another Middle East terrorist group, or in a domestic cell of fanatical anti-Semites, or possibly both… They vowed continued cooperation with US and Israeli intelligence services.”

But in the weeks, months, years, and decades to come, those promises were never fulfilled, and justice for the victims proved elusive. When Isaacson flew out of Argentina a week later, he had no idea that solving the case would be one of his most frustrating and futile challenges to come.

JI: “To keep the pressure on, to keep the spotlight focused on Argentina, we would publish every year on the anniversary a report on what happened with the investigation. Where is the justice? Where is the accountability? What really happened? Argentina had a history of Nazi sympathisers and Nazi SS guys who ended up living there – a whole pool of potential people who hated Jews and would very much like to attack a large Jewish target. It was clear it was a friendly environment for people who hate Jews.”

Harris resolved to go to Argentina annually, which he has done for the last 25 years.

DH: “This went very, very high on our agenda. Over the months and years, there have been countless meetings with Argentine officials, Argentine presidents, foreign ministers, interior ministers, justice ministers, ambassadors to Washington, consuls general in New York, and other cities across the US I don’t know how many. To make a long story short, frustration on steroids.”

Dina Siegel Vann worked as director of political affairs for the Mexican Jewish community at the time of the attack. Mexico was already in political turmoil and the news out of Argentina came as yet another troubling development.

DSV: “As a Latin American Jew, it shocked us all… We were not used to Jewish institutions in the region being attacked the way this happened. This really increased our sense of vulnerability and made us aware we were a target. We could be a target anywhere, anytime.”

Harris said Argentina had been woefully ignorant of terrorist threats in the Middle East and had turned a blind eye to the tentacles of those terrorist networks in Latin America – particularly where the borders of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay meet. That region, known as the Triple Frontier, had become a hub for Shi’ite Muslim terrorist groups, like Hezbollah.

DH: “You had a combination of things in Argentina. There was a lot of corruption and there was a lot of unpreparedness. Argentina was thousands and thousands of miles away from the Middle East. They weren’t ready for this. They didn’t understand Middle East terrorism, how to track it, how to know it, how to confront it. This was out of their realm. As it emerged that this had international fingerprints, as it emerged that the likeliest suspects were Iran and Hezbollah, as it emerged that there might well be local connections with the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires and the Triple Frontier, there were a lot of people in the system who did not want to know the answers.”

When Siegel Vann joined AJC in 2003, the crime was still unsolved. After a nine-year trial with 588 volumes of evidence and 1,284 witnesses, a court acquitted 22 Argentines who had been indicted as the local connection behind the terrorist attack. Instead, the head judge involved in the investigation, the former president, and the intelligence chief were indicted for obstructing justice.

DSV: “It’s a betrayal in so many ways – a betrayal of Argentina’s commitment to a democracy of inclusion and to the Jewish community as a valued element or sector of Argentine society; a betrayal of several governments’ commitments to seeking justice. For whatever reasons – economic, political – they chose to betray the commitment they had made to the Jewish community not only in Argentina but around the world.”

That betrayal led a group of family members who lost their loved ones, to give up on the government, file a lawsuit, and appeal to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In 2005, the Argentine government admitted to that commission that successive administrations had not done enough. Government officials promised a clear and transparent investigation and introduced the possibility of reparations for victims’ families. But even that did not bear fruit.

DSV: “The Argentine state had to accept its culpability and made several commitments that it hasn’t fulfilled – controlling entries and exits from the country, putting in place contingency plans for disasters, and others. They are still pending.”

Then President Nestor Kirchner had already taken one positive step in 2004 by appointing special prosecutor Alberto Nisman to resume the investigation. Within two years, Nisman produced an 801-page report, indicting seven Iranian officials, including former President Ali Akbar Rafsanjani and Hezbollah’s senior military commander Imad Mugniyeh.

The mastermind of the crime, Nisman said, was a man named Mohsen Rabbani, a former leader at a mosque in Buenos Aires called Al Tawhid who went on to serve as a cultural attaché at the Iranian Embassy.

Based on Nisman’s report, in 2007 Interpol issued “red notices,” or arrest warrants for five Iranian officials – many of whom had left the country before the bombing – and called for their extradition.

That same year, Kirchner was succeeded by his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, in an election hailed as a victory for the Jewish community.

During the first years of her presidency, she regularly appealed to the United Nations General Assembly to put pressure on Iran. She often came with a delegation of AMIA survivors. And when Iranian officials stood to speak at the UN, Argentine delegates symbolically walked out.

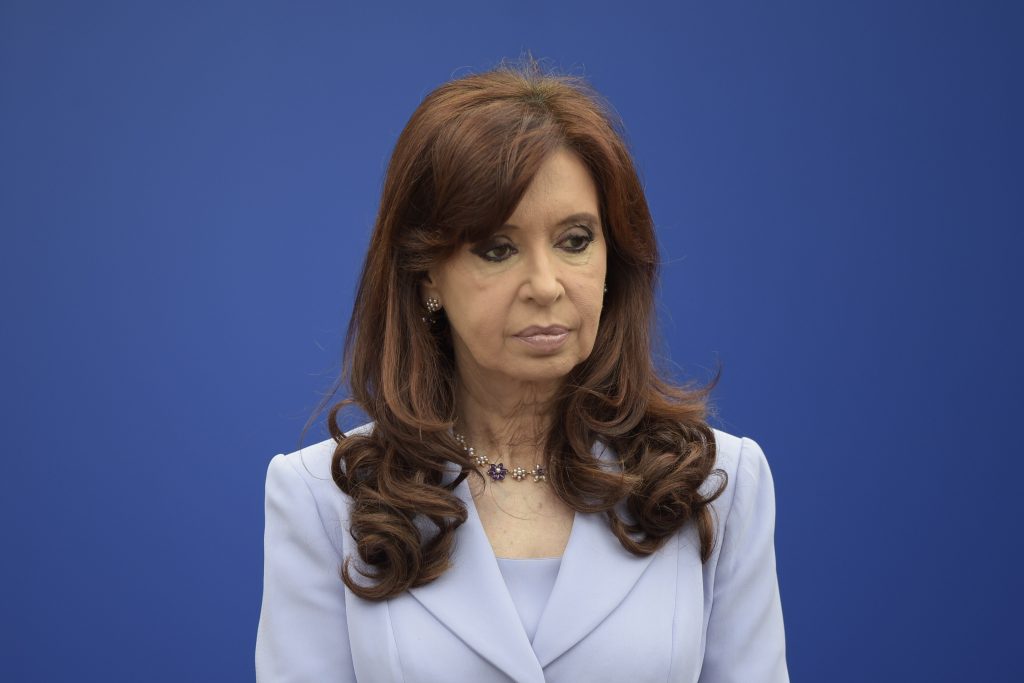

Former Argentinian President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner: Now facing cover-up charges

But after her husband’s death in 2010, Fernandez de Kirchner seemed to do an about-face. She travelled to the United Nations without AMIA survivors and when then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad rose to speak, Argentina’s delegates stayed seated.

In 2012, Pomerantz heard from a journalist.

DP: “He announced that Argentina is going to sign an agreement with Iran in a meeting in Syria. The reaction of all of society in Argentina was [that] it’s not credible. To sign an agreement with the perpetrators, what kind of decision is that? One year later, we discovered it was true. Since the first moment, it was clear that Iran was to be the beneficiary.”

Fernandez de Kirchner and Iranian leaders signed a memorandum of understanding in 2013 to launch a joint investigation dubbed a “truth commission.” The agreement said nothing about the Iranian suspects already named.

“We will never again let the AMIA tragedy be used as a chess piece in the game of foreign geopolitical interests,” Fernandez de Kirchner tweeted.

DH: “This was beyond insanity. I said at the time that it was like asking Nazi Germany to help establish the facts of Kristallnacht. Every Argentine president for the last 25 years had looked us earnestly in the eye and said we’re different from everybody else. We’ll get to the bottom of this. We care about this as much as you do. This was our country. This was an attack on our country. And guess what? They’ve all come up short.”

The memorandum raised Nisman’s suspicions too and he launched a separate inquiry. Hours before he was to testify about the results in front of the Argentine Congress, he was found dead in his home, having been shot in the head. Argentine Authorities initially said it was suicide, but not many believe that story.

The fate of murdered prosecutor Alberto Nisman has not been forgotten

Eventually, Harris and Siegel Vann took a broader approach of trying to persuade Argentina to declare Hezbollah a terrorist organisation and put safeguards in place to prevent another attack.

DH: “The question has remained for us: ‘Do Iran and Hezbollah and kindred spirits view Argentina as a soft target? They had two successful terrorist attacks. They did so with seeming impunity. Could there be a third?’ Part of our agenda became, how do we, broadly speaking, get Argentina to adopt an anti-terrorism law, which they did not have? And in doing that, how do we get Argentina to create their own terrorism list and shouldn’t Hezbollah be on the list? After all, Hezbollah was involved in two deadly attacks. We have not had success with the Hezbollah issue in Argentina until now. But things do not move swiftly or linearly in Argentina, I’ll put it that way.”

At one point, Harris met with the Argentine justice minister to push for that anti-terrorism legislation.

DH: “It was one of many meetings, but I remember that one very vividly. I was sitting across from the justice minister. At a certain point I said to him ‘Mr. Minister may I ask you a question? If I want to support Hezbollah, can I go to one of the hotels in Argentina, take a ballroom and host an event and raise money for Hezbollah? Is that legal or illegal?”

“He said almost immediately ‘You could not do it,’ and I said to him ‘I’m glad to hear that. Could you tell me on what basis would I not be able to do it?’ He said ‘Because Hezbollah is on the United Nations terrorism list, and we in Argentina abide by the UN terrorism list.’ I said to him ‘Mr. Minister, with respect, Hezbollah is not on the United Nations terrorism list.’ He said ‘Are you sure?’ And I said ‘Yes, sir, I am,’ at which point we had the very unusual situation where he essentially asked for a time out. He and his entourage stood up on their side of the conference room and they huddled, and then they came back, as I remember it, he said ‘Yes, my staff confirmed you’re right.’”

“All of this stuff is such a tale of tragedy, of incompetence, of empty-handedness in the end.”

Pomerantz said the attack killed and injured so many of the small community, there are very few degrees of separation between someone killed in the blast and other Jews in Argentina.

Still, the Jewish community in Argentina, the largest in Latin America, has never been more vibrant, Pomerantz said.

DP: “The Jewish community is standing and fighting. We are seeing the best situation for our community. They didn’t win.”

In mid-July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo travelled to Buenos Aires, where President Mauricio Macri recently signed a decree that adds Hezbollah to a registry of terrorist organisations, and aims to curb its terrorist activity by freezing its assets – a long overdue step in the right direction.

DSV: “If Argentina wants to be taken seriously, as a serious country, as a country of laws, a country that values life, I think that it will have to eventually come clean about what happened. President Macri now has included something where he speaks at the United Nations at the General Assembly, calling on Iran to accept its culpability and extradite those responsible. That’s good. They feel it’s part of their national agenda, to keep the memory alive.”

Isaacson insists it’s not too late to confront the past.

JI: “It needs a much higher level of government commitment and commitment to transparency and revelation of the cover up that existed for a longtime. A boldness and self-critical aspect that will allow for a real examination of what happened and the intent to cover up what happened. Justice delayed is justice denied. That doesn’t have to be the end of justice – It could still happen. It could still be pursued and realised. Hey, we’re still chasing some old Nazis.

“Would it bring back 85 souls? Would it relieve Argentina of the guilt of covering up this massive crime? No. But it would be a positive step.”

Pomerantz remains sceptical.

DP: “After 25 years, it’s not possible to be optimistic.”

© American Jewish Committee (www.ajc.org), all rights reserved, reprinted by permission.

Tags: Argentina, Hezbollah, International Jewry, Iran, Terrorism