Australia/Israel Review

Is Palestinian reconciliation serious this time?

Nov 27, 2017 | Michael Herzog

Michael Herzog

On 1 November, the Hamas movement began the process of handing over the three Gaza border crossings to the Palestinian Authority (PA), as part of the September reconciliation agreement signed between them under Egyptian auspices. This agreement looks far more serious than the numerous ones that have been signed in the past and has created a new reality where the PA is back in Gaza for the first time in ten years and is assuming responsibility for the Strip in the civilian arena.

The reconciliation deal has already experienced a major security challenge. On 30 October, Israel blew up a cross-border offensive tunnel in Israeli territory which had been dug by the Islamic Jihad movement in Gaza. As Islamic Jihad and Hamas activists rushed to the tunnel on the Palestinian side, at least 12 of them, including senior military commanders, were killed in explosions and the tunnel’s collapse. Although both Hamas and Islamic Jihad vowed revenge, it seems that Hamas currently prefers containment to escalation so as not to undermine the reconciliation deal.

The Elements that led to the Deal

There are six converging elements that led to the deal at this particular time.

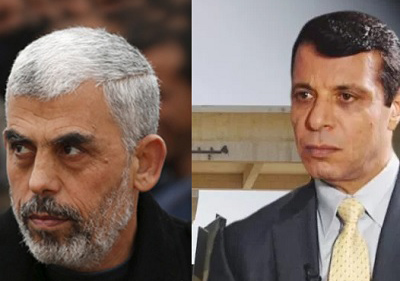

The first is the new leadership of Hamas, especially the election earlier this year of Yahya Sinwar as the movement’s effective leader. Following his election, there was much speculation in the Israeli media that Sinwar would lead Hamas to war with Israel as he is one of the founders of the military wing and an extreme militant. Yet Sinwar appears more pragmatic than meets the eye. His mentality is not that of a typical Muslim Brotherhood ideologue. While ideologically he remains committed to Israel’s destruction, he understands the serious challenges of governing Gaza. Sinwar is the one who pushed Gaza towards this reconciliation deal and his personality helped drive the movement – including the military wing – to accept it.

The second, related element is the abject failure of Hamas in governing Gaza and its inability to provide basic solutions for the people of Gaza. During its ten year rule of Gaza, Hamas dragged the Strip into three rounds of armed conflict with Israel, isolated it and neglected it in order to build its own military wing – to the point of causing an acute economic, infrastructural and humanitarian crisis. This is part of a wider pattern of Islamists failing in government, which has been demonstrated in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere. As noted, the new Hamas leadership now realises that governing Gaza is a big headache and it is happy to transfer that headache to the PA.

The third and fourth elements are the respective roles played by two arch-rivals; Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and former senior Fatah official Muhammad Dahlan, who have each tried to make use of Hamas’ strategic weakness to advance their own interests. As of early 2017, Abbas cut critical financial aid to Gaza in the hope of bringing Hamas to its knees and forcing it to accept all of the PA’s demands for reconciliation. This exacerbated the crisis in the Strip and no doubt played a role in pushing Hamas to ultimately accept a reconciliation deal.

However, the deal might still not have happened were it not for the intervention of Dahlan. The latter used the PA-Hamas crisis to step in, broker conciliation talks between Hamas and Egypt and provide some solutions for Gaza, especially to alleviate the electricity crisis and to promise the permanent opening of the Rafah Crossing by Egypt. Abbas’ fear that Dahlan might cash in on the deal at his expense provided a powerful motivation for the PA President to become part of the Egyptian reconciliation efforts and return to Gaza, having previously refused to play a role in the territory since he lost Gaza to Hamas a decade ago. I don’t think Abbas desired this specific outcome of his initial pressures on Hamas – he isn’t overly happy about the reconciliation deal – but given the roles played by Egypt, Dahlan and Hamas, Abbas was manoeuvred into the reconciliation deal for lack of a better choice.

The fifth element is the role of Egypt. Given its close relations with Israel, the US and Dahlan and its leverage over Hamas and the PA, Egypt is uniquely positioned between all the relevant actors. Egypt recognised the opportunity for a reconciliation deal at this time, stepped up its pressure on the relevant parties and skilfully leveraged them.

The final element that led to the deal is the upcoming launch of the US-initiated peace process, expected by the parties early next year. The Trump Administration has been saying that it’s hard to speak of a two-state solution as Gaza is not controlled by the PA, so it has become important for Abbas to show the Americans and the rest of the world that he is in control of Gaza and that he also represents the Strip.

Differing perspectives of the reconciliation deal

The deal now being implemented on the ground is still a partial one and some of the big questions, especially the future of Hamas’ military wing and its role in PLO, await the parties down the road.

For now, the two sides are implementing what they could agree on. Hamas’ headache of providing electricity, food and jobs to the people in Gaza has now been moved over to the PA.

The upside of the deal for the West and Israel lies in the fact it turns Hamas away from Qatar and towards Egypt and the UAE; it allows for addressing the humanitarian crisis in Gaza; and it enhances the potential for a long-term ceasefire between Hamas and Israel.

But it also raises serious questions. Despite the agreement, there is a very different view of the deal in Ramallah than in Gaza. For Abbas, the deal is about Hamas handing over all responsibilities in Gaza to the PA, so he can present himself as representing both areas. For Hamas, the reconciliation deal is a two-way street. It should allow Hamas free political action in the West Bank and to join the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), the overall representative body of the Palestinians.

Ultimately Hamas’ goal is to take over the PLO and the Palestinian National Movement in the post-Abbas era. From Hamas’ perspective, it filled the void after Arafat’s death in late 2004 (when it won the Parliamentary elections in 2006), and now it wants to fill the void after the ageing Abbas departs the scene.

Notwithstanding the pragmatism shown by Hamas in this deal, it does not represent a deep ideological reorientation of the movement. As its leadership repeatedly emphasises, Hamas is not going to give up its military wing, forsake its Islamist character and agree to recognise Israel.

Hamas plays both sides

The visit by a senior Hamas delegation – led by its newly-elected deputy leader, Saleh al-Arouri – to Iran soon after the signing of the deal (followed by a meeting between Arouri and Hezbollah’s leader Nasrallah in Beirut) was intended to demonstrate that Hamas is not merely in the Egyptian orbit but continues to foster excellent relations with the regional “axis of resistance” led by Iran. It was probably also intended to defy Netanyahu and his three conditions for accepting the reconciliation deal, one of which was for Hamas to cut relations with Iran.

First and foremost, Hamas wants to keep Iranian financial and military support. Obviously, the Iranians are unhappy about this deal but it is hard for them to say they are against Palestinian unity. Hamas wants to show the Iranians that it still considers itself part of the “resistance camp” and deserves support from Iran. That’s part of the reason why Hamas has been explicit in refusing to disarm.

So Hamas is playing both sides of the equation – it works with Egypt and the PA on implementing a reconciliation deal which would require it to abide by a ceasefire, and at the same time it flirts with Iran on camera and strives to keep and develop its military and terror capabilities.

The election of Sinwar has somewhat blurred the lines between the two wings of Hamas. Sinwar made sure to emphasise that the reconciliation deal was approved by the military wing. The idea behind appointing Saleh al-Arouri as number two in the movement was not only to give representation to Hamas in the West Bank (because the other Hamas leaders are all from Gaza) but also because al-Arouri – who is now based in Beirut having been asked to leave Turkey and subsequently Qatar and who was behind the kidnapping and murder of the three Israeli teenagers in 2014 – still carries the flag of resistance.

Open questions regarding reconciliation

While Hamas, by and large, has implemented its part of the deal, the PA has yet to lift its sanctions against Gaza and resume its full financial injection to the Strip. It also appears that while Hamas agreed to suspend terror initiatives in the West Bank for the sake of reconciliation, it expected in return that the PA would cease pressuring Hamas’ political activities in this area: Hamas has so far been disappointed.

Down the road, there are some major questions that haven’t been resolved and remain open:

The future of Hamas’ military wing

One of the big questions confronting us is what happens to the military wing of Hamas. Abbas has said he will not accept the “Hezbollah model” (in which an organisation is part of the government but maintains its own military wing), but the Egyptians delayed any discussion on this issue to the more distant future. Hamas continues to maintain that it will never disarm. This situation also raises a question for Israel over who it will hold responsible for future rockets that may be fired from Gaza into Israel. In the meantime, the PA and Hamas have to come to terms regarding the tough question of if and how to integrate their internal security bodies in Gaza.

For Israel, disarming Hamas (and all other armed Palestinian factions) is part of the principle (agreed in past negotiations) stipulating that a future Palestinian state must be demilitarised.

Hamas, the PLO and PA elections

The current reconciliation agreement is based on the 2011 Cairo Agreement, which stipulates that Hamas will become part of the PLO. But while there continues to be a technical debate as to the future level of representation of Hamas in the PLO (with Hamas demanding 40% and Abbas not willing to go above 30%) there is an open question as to whether this part of the agreement will actually be implemented by Abbas.

Under the Cairo Agreement, the two parties should also call, within a specified timeframe, for presidential and parliamentary elections in the PA (last held in 2005 and 2006 respectively). Will Abbas call elections (and run in them) if he thinks he might lose?

The Palestinian government and the peace process

Once the US launches its peace initiative – whatever that may include – one assumes it will want to lead to direct negotiations between Israel and the PA. But will Israel be expected to negotiate with a Palestinian unity government that includes Hamas, or is backed by it? Netanyahu has said this isn’t going to happen and his position has been supported by the US. In response, Abbas stated that any minister in the new government will have to recognise Israel before being appointed, yet will that satisfy Israel and the US? Moreover, the composition of the unity government remains undecided. Will it be made up of politicians or technocrats? In any event, it’s an issue that might complicate a future peace process.

Palestinian public salaries and fixing the infrastructure

According to the reconciliation deal, both parties committed to resolve the issue of salaries of Hamas civil servants by February 2018. The UAE is willing to provide some funding but not for all 40,000 people. An EU official recently calculated that covering salaries alone would amount to approximately US$40 million a month, around US$500 million per year. I don’t see any enthusiasm in the international community to provide funds to cover this financial burden or for the major investments required to fix the collapsing infrastructure in Gaza, so it is unclear how this will be resolved.

Michael Herzog, a retired brigadier general in the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), is the Israel-based Milton Fine International Fellow of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He is also currently a Senior Visiting Fellow at the British-Israel Communication and Research Centre (BICOM). © BICOM, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Palestinians