Australia/Israel Review

UNIFIL’s end

Sep 19, 2025 | Sarit Zehavi

Forty-seven years of failure in Lebanon

On August 25, the UN Security Council (UNSC) adopted a historic resolution, No. 2790, ending the mandate for the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) after some 47 years. The decision is unprecedented – not only because it marks the conclusion of an international mission that lasted nearly five decades, but also because of the messages and provisions it contains. While it represents a significant diplomatic achievement for Israel, it also underscores a shared recognition of UNIFIL’s utter failure. In addition, the resolution raises questions regarding the international community’s ability to genuinely understand the challenge represented by Hezbollah’s Iranian-supported military dominance of Lebanon.

At the outset, it is important to note that the UNSCR 2790 contains several elements that warrant careful consideration. A prominent example is the Security Council’s emphasis on the safe return of civilians on both sides of the “Blue Line” Israel-Lebanon border to their homes.

From Israel’s perspective, the return of Lebanese civilians to villages situated immediately along the border – mere metres from Israeli communities – seems tantamount to the reestablishment of Hezbollah’s presence at the frontier. The historical reality of southern Lebanon over the past four decades has been unequivocal: Hezbollah thoroughly entrenched itself within the civilian infrastructure of Lebanese towns and villages, sustained by extensive Shi’ite communal support, and evolved into an existential threat to Israeli border communities. This is a situation Israel is determined not to allow to recur.

Although Hezbollah has suffered significant losses in the present conflict, it has not relinquished its resolve to continue waging war against Israel, while utilising Lebanese civilians as human shields. This determination is based on a strong religious belief, part of the radical interpretation of Shi’ite Islam exported by the Ayatollahs in Iran.

UNSCR 2790 outlines a proposal to deploy an additional 6,000 Lebanese Armed Forces personnel to southern Lebanon. At first glance, this measure appears intended to mitigate a potential security vacuum following UNIFIL’s withdrawal. In practice, however, such a vacuum does not exist. UNIFIL has never fulfilled any substantive role in the area: it has neither reported systematically on Hezbollah’s activities in the south nor undertaken measures to facilitate its disarmament nor done anything else that substantively “keeps the peace” along the border.

We have recently seen images circulating in Western media depicting cordial joint UNIFIL patrols with the Lebanese army and the discovery of a single rocket launcher and some rockets – the first time in nearly two decades UNIFIL has “found” any weapons in the area. The images are not representative of the reality on the ground. They obscure the vast scale of Hezbollah’s extensive weapons build up in the southern villages in violation of the relevant UNSC Resolutions and UNIFIL’s longstanding and complete inability to confront or constrain it – or indeed, to even document it.

From Israel’s standpoint, there is no compelling requirement in 2790 to suspend its strikes against Hezbollah’s infrastructure, or demand for the withdrawal of IDF forces from the five positions situated on the Lebanese side of the border that it continues to hold since last year’s war with Hezbollah, except in the context of Lebanon fulfilling its obligations to disarm Hezbollah and assert full control over southern Lebanon. In the meantime, Israel continues to pursue a proactive strategy of almost daily strikes against Hezbollah. It is particularly significant that over half of the 500 strikes conducted since the ceasefire have occurred south of the Litani River – the very core of UNIFIL’s designated area of operation.

The resolution does introduce a set of additional challenges for the IDF. Chief among them is the call for the deployment of approximately 10,000 Lebanese Armed Forces personnel in the previous UNIFIL area, coupled with the references to Israel withdrawing from its five positions and ending its military strikes in Lebanon. These provisions may be construed as implicit conditions for the termination of UNIFIL’s mandate and could possibly provide a pretext for the continuation of its activities after they are scheduled to end.

Although 2790 reiterates earlier Security Council decisions (notably Resolutions 1559 and 1701) that call for the disarmament of Hezbollah across the entirety of Lebanon, it also limits the scope of responsibility entrusted to the newly established post-war “Mechanism” – an oversight body that includes the United States and France – to the geographic area of UNIFIL’s operations alone. This could effectively allow the Lebanese Government to refrain from taking action against Hezbollah north of the Litani River, thus maintaining Hezbollah’s freedom of action in those areas.

The five-party Mechanism is designed to facilitate more efficient channels of communication regarding violations of the cease fire agreement, thereby enabling the IDF to transmit reports and to request action from the Lebanese Armed Forces on the basis of credible intelligence. The Mechanism incorporates the active involvement of senior military officials from the United States and France, alongside representatives of Israel, Lebanon, and UNIFIL. Developments in recent months demonstrate that this framework renders any UN role largely redundant.

Importantly, the resolution also extends UNIFIL’s mandate until December 31, 2026, and then grants an additional year to facilitate an orderly withdrawal. In practice, although the resolution formally announces the termination of the mandate, it also prolongs the force’s presence until the end of 2027. This stands in contrast to previous extensions, which were limited to one year at a time. Accordingly, the declaration of UNIFIL’s termination is more theoretical than substantive. The resolution does not delineate the stages of dismantlement, justify the protracted timeline, or specify who is responsible for supervising and implementing the process.

To understand how urgent it is to end the UNIFIL mandate, one must look at the report recently published at Alma Research and Education Centre under the title “The UNIFIL Mandate Must End” (July 2025). The report summarises UNIFIL’s activity and sketches a grim picture: not only did this force not contribute to Israel’s security or Lebanon’s stability, it sometimes even served as a cover that allowed Hezbollah to expand and prepare for war unhindered.

Since its establishment in 1978, the UNIFIL mandate was conceived as a provisional mechanism designed to facilitate Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon and to support the reassertion of Lebanese sovereignty. Over time, the mission expanded numerically and in terms of its budget, yet this quantitative growth was not matched by any corresponding enhancement of its operational effectiveness. With the adoption of Security Council Resolution 1701 in 2006, UNIFIL was entrusted with a critical mission: not only to monitor the ceasefire, but also to support the Lebanese Armed Forces in extending their deployment across southern Lebanon and in disarming Hezbollah north of the Litani River – a zone extending up to 27 km from Israel’s border.

In practice, however, UNIFIL evolved into a passive mediating presence, systematically avoiding direct confrontation with Hezbollah and maintaining a deliberately low profile, even in the face of manifest and recurring violations of the agreements. The force’s activity focused mainly on humanitarian assistance.

Recent PR images have shown UNFIL working with the Lebanese army to find some small caches of arms. But these are the first time in nearly two decades that UNIFIL has discovered any weapons whatsoever (Image: Shutterstock/ Sebastian Castelier)

UNIFIL repeatedly failed to report Hezbollah’s persistent violations, including the construction of offensive tunnels and the establishment of weapons depots within civilian areas – some even in close proximity to UNIFIL bases. In many instances, when the Force sought to inspect suspected sites, it was obstructed or attacked by local residents operating under Hezbollah’s direction, leading to its withdrawal. Rather than functioning as an effective monitoring and enforcement body, UNIFIL assumed a symbolic role that permitted the international community to disregard the realities on the ground.

Over the years, UNIFIL maintained that its mandate precluded it from entering residential structures in which Hezbollah concealed weapons. Nevertheless, the substantial quantities of armaments uncovered by manoeuvring IDF forces in proximity to the border during last year’s war, together with the exposure of multiple storage sites, clearly demonstrated that Hezbollah made use not only of Lebanese villages but also of open, non-residential areas. In the latter case, UNIFIL consistently refrained from conducting patrols or identifying such stockpiles, despite the absence of any conceivable legal impediment to doing so. And those Hezbollah weapons were deployed there as part of the plan to occupy the northern part of Israel.

During last year’s Israel-Hezbollah conflict, UNIFIL was not only ineffective but also harmed the IDF’s efforts to dismantle Hezbollah’s weapons near the border. By refusing to evacuate combat zones, it placed its own soldiers at risk, while its unexpected presence on the battlefield endangered IDF troops, forcing them to cease their fire and enabling terrorists to escape.

Last year’s conflict demonstrated that UNIFIL’s problem is fundamental – the United Nations, as an institution, does not constitute a framework capable of actively pursuing the disarmament of Hezbollah. Consequently, UNIFIL functioned less as a security instrument and more as a costly mechanism that enables Lebanon to evade responsibility for addressing its own security challenges. Regrettably, the latest resolution once again fails to place the onus of responsibility for dealing with the instability and violence created by Iran’s sponsorship of Hezbollah in Lebanon on the Lebanese state.

For four decades, UNIFIL’s mandate was extended incrementally through short, annual renewals. By contrast, the recent decision granted an unprecedented extension of two and a half years – albeit with a reversable call to wind up UNIFIL by the end of 2027. Until the end of 2026 the force is expected to continue its current operations despite the near-universal recognition that its effectiveness has been negligible or counter-productive.

This outcome can be attributed primarily to political considerations: the desire to preserve diplomatic flexibility and the concern that a sudden withdrawal might create a power vacuum.

As noted above, however, this supposed vacuum does not exist. The true vacuum was, in fact, created by UNIFIL’s persistent failure to fulfill its mandate. The force has neither contributed to the disarmament of Hezbollah nor provided accurate reporting on the extensive accumulation of armaments in southern Lebanon. On several occasions, its presence has even undermined Israel’s operational capacity to counter the threat.

Thus, the continuation of UNIFIL’s presence until the end of 2027 lacks strategic justification. Each additional day that the force remains on the ground represents a squandered opportunity to pursue more effective security arrangements. A rapid transition to a framework in which Israel and Lebanon, with direct American and French support, assume responsibility for security in southern Lebanon would offer a much more cost-effective, operationally efficient, and strategically sustainable alternative.

Tags: Hezbollah, Israel, Lebanon, UNIFIL, United Nations

RELATED ARTICLES

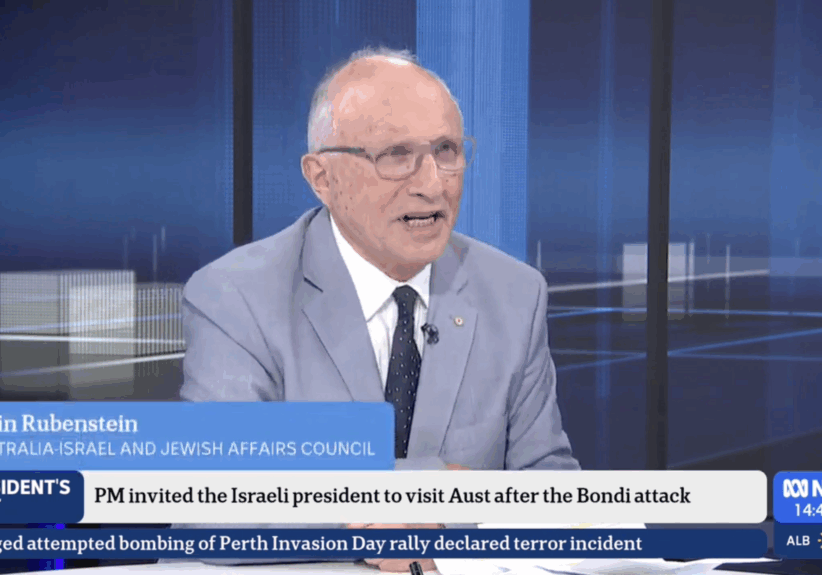

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio