Australia/Israel Review

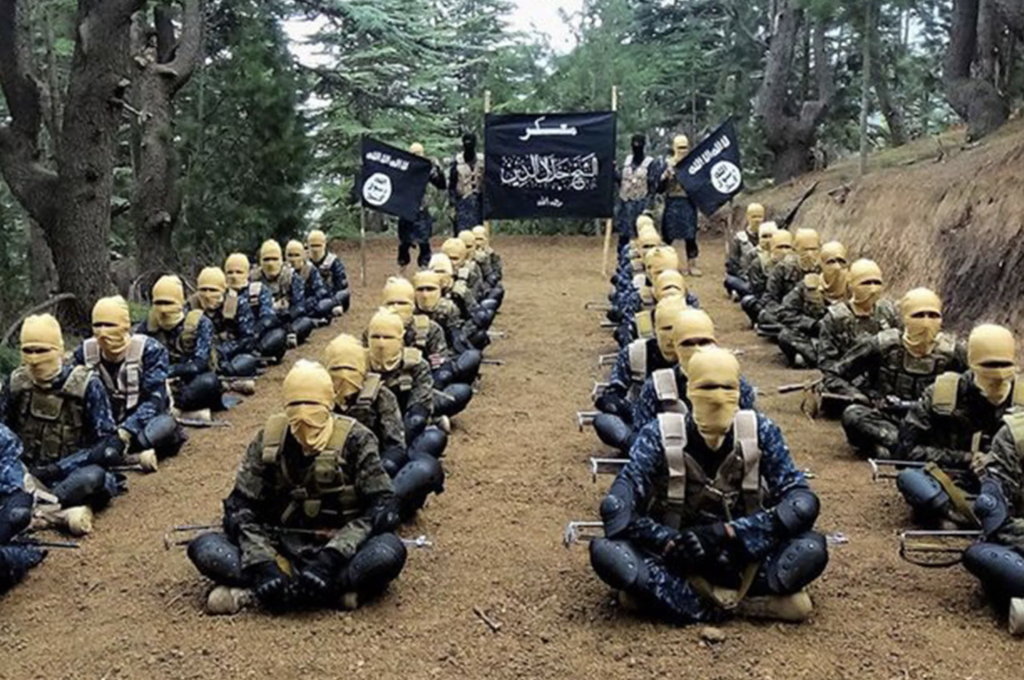

The Rise of ISIS-K

Sep 17, 2021 | Thomas Joscelyn

What we know – and don’t know

A suicide bombing outside the airport in Kabul on August 26 saw at least 13 US service members killed, while more than a dozen others were wounded. Estimates say more than 170 Afghans perished.

The Islamic State-Khorasan Province (often referred to as ISIS-K by the US Government) quickly claimed responsibility for the heinous attack. No one was surprised. In the days leading up to the bombing, American officials, including US President Joe Biden, repeatedly warned that ISIS-K could strike at any time.

And so it did.

Here are answers to some of the basic questions that are being asked about ISIS-K.

Who is the leader of the Islamic State-Khorasan Province?

President Biden vowed following the attack to retaliate against those responsible for the bombings. One of America’s likely targets is the ISIS-K leader, a terrorist known as Shahab al-Muhajir.

The Islamic State’s senior leadership appointed al-Muhajir as its wali (or governor) for the region in June 2020, after a string of his predecessors were killed or captured in counterterrorism operations. Al-Muhajir is an effective operator. As a team of experts working for the UN Security Council reported this past June, al-Muhajir “served as [the Islamic State’s] chief planner for high-profile attacks in Kabul and other urban areas.”

Al-Muhajir’s men are prolific terrorists. The UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan documented 77 attacks that were either claimed by ISIS-K or attributed to it in the first four months of 2021 alone. Some of these were carried out in Kabul, where al-Muhajir’s network has regularly targeted civilians, as well as the now-deposed Afghan government.

How many men does the Islamic State have in Afghanistan?

No one really knows. All estimates are fraught with problems. Terrorist organisations don’t publish their rosters, meaning a lot of guesswork is involved in coming up with figures. US estimates of the manpower for the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and the Taliban have been flawed for years.

According to the UN Security Council, ISIS-K was thought to have somewhere between 1,500 and 2,200 members in eastern Afghanistan earlier this year. But there are reasons to suspect that the group has hundreds of other members elsewhere throughout the country as well, including inside the Afghan capital. The Taliban’s jailbreaks have reportedly freed hundreds of additional ISIS-K loyalists, too.

Why is ISIS-K opposed to the Taliban?

When the Islamic State declared its caliphate in Iraq and Syria in June 2014, its leaders immediately rejected the legitimacy of all other Muslim and jihadist authorities – including the Taliban. According to the Islamic State’s scheme, once its men set foot on the soil of any country or region, all Muslims in the vicinity owe their allegiance to its caliph. The first Islamic State caliph was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. And when the first iteration of ISIS-K was formed in 2014, the group immediately demanded that all Muslims in Afghanistan bend the knee.

The Taliban weren’t and aren’t having it. The Taliban’s leadership has consistently rejected the Islamic State’s attempts to usurp its authority, including during the reign of Baghdadi’s successor, a terrorist known as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi.

The Taliban and al-Qaeda fought for nearly 20 years to resurrect the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan – the authoritarian regime that was toppled during the 2001 US-led invasion. ISIS-K rejects the Islamic Emirate’s legitimacy outright.

The Taliban and ISIS-K have repeatedly fought one another. Al-Qaeda has, naturally, fought on the Taliban’s side. And ISIS-K usually has the losing hand in this intra-jihadist conflict.

Their battles aren’t just about which one is the rightful ruler of Afghans. ISIS-K’s initial leadership was made up of defectors from the Taliban, al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Taliban, as well as other affiliated groups. These defectors likely had their own personal agendas, in addition to ideological objections to the Taliban’s rule.

This dynamic will continue to be a thorn in the Taliban’s side, as ISIS-K provides an outlet for any disaffected leaders or fighters. ISIS-K has its own indigenous recruiting networks as well.

Does ISIS-K pose a threat outside of Afghanistan?

Yes. The UN Security Council’s expert staff has identified a body known as the Al-Sadiq office as a regional node in the Islamic State’s global network. Al-Sadiq is both “co-located” with ISIS-K in Afghanistan and “pursuing a regional agenda in Central and South Asia on behalf of the” Islamic State’s global leadership. In other words, ISIS-K isn’t a standalone unit – it is working with other parts of the Islamic State’s network to export terror outside of Afghanistan.

ISIS-K has recruited fighters from throughout the Central Asian states, with the goal of exporting jihad to them. The Islamic State views these countries as new ground for expanding its caliphate project. Thus far, however, the group has demonstrated only a small operational presence in these countries. In July 2018, for instance, a team of Islamic State terrorists ran over American and European cyclists in Tajikistan, killing four people.

South of Afghanistan, in Pakistan, ISIS-K has a more developed operational capability. The group has conducted a string of operations inside Pakistan over the past several years.

ISIS-K poses some degree of threat outside of Central and South Asia as well. In the summer of 2016, three men allegedly conspired to carry out terrorist attacks in New York City on behalf of the Islamic State. American investigators discovered that the trio had at least some contact with ISIS-K’s jihadists.

In April 2020, German authorities broke up a cell of four Tajik nationals who were allegedly preparing to attack US and NATO military facilities. Earlier this year, the CTC Sentinel published a report by Nodirbek Soliev, who expertly summarised the ties between this cell and Islamic State figures in Afghanistan and Syria.

To be clear: The overwhelming majority of ISIS-K’s operations are conducted within Central and South Asia. But American officials will have to try to keep tabs on the group after all US military personnel were withdrawn, because no one can rule out the possibility that the outfit may try something in the West.

Is there any evidence showing that the Taliban and ISIS-K collude with one another, despite their obvious differences?

The answer to this one is tricky. According to the UN Security Council’s experts, some countries claim that there is evidence showing that the infamous Haqqani Network has used ISIS-K cells in Kabul as a cutout for operations the Taliban don’t want to claim, including bombings that kill a large number of civilians. The Haqqani Network is an integral part of the Taliban, and also closely allied with al-Qaeda. It is notorious, in part, because the Haqqanis have conducted some of the biggest terrorist attacks in Kabul’s history – to date.

The UN team has cited intercepts allegedly showing that Haqqani commanders had foreknowledge of ISIS-K attacks. But is this evidence that the Haqqanis were flying false flags? Or had these Haqqani commanders simply defected to ISIS-K? Shahab al-Muhajir, the leader of ISIS-K, may be a former Haqqani operative himself – though that hasn’t been proven.

In the end, the Haqqani-ISIS-K cutout theory is just that – a theory. We should be careful about running too far with it, especially absent solid evidence. On Aug. 26, President Biden said there is no evidence showing that the Taliban had cooperated with ISIS-K in the bombing outside Kabul’s airport. I don’t know how the President could have already known that just hours after the fact, especially given that the Taliban were manning “security” checkpoints nearby.

Still, ISIS-K has its own agency and its own incentives for killing Americans, Afghans, and others at the Kabul airport. The Taliban and al-Qaeda won the war, so ISIS-K had every reason to steal their thunder. The bombings outside the airport will undoubtedly help with the Islamic State’s global recruitment efforts.

ISIS-K’s claim of responsibility took direct aim at the Taliban, pointing to the fact that the Taliban had cooperated with the US in the evacuation of Americans and others. This argument is intended to undermine the Taliban’s jihadist credentials – and their legitimacy as a government. And as the UN team has noted, the cutout theory is a controversial topic among member states – some of which dismiss it out-of-hand.

Can the Taliban be America’s counterterrorism partner, as some have argued?

No. Sometimes the enemy of my enemy is just my enemy – not my friend. Such is the case with the Taliban, which remain intertwined with al-Qaeda. Thus far, the Taliban and al-Qaeda have been content to watch America retreat in humiliation. They wanted US forces gone, so they can get down to the business of restoring their Islamic Emirate. This has been their main religious and political goal all along.

Al-Qaeda is banking on the benefits of jihadist rule in Afghanistan, as it will be able to freely recruit, train and plot.

Most importantly, no one should ever trust the Taliban. In late August, the group’s spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, told NBC News there is “no proof” that Osama bin Laden was responsible for the 9/11 hijackings. The Taliban have repeated this lie many times since 9/11 – even as al-Qaeda repeatedly advertised its responsibility for the deadliest terrorist attack in history.

It says much about the Taliban, and their true agenda, that they can’t be honest about 9/11 after all these years.

The bottom line: ISIS-K remains a threat – both in Kabul, and elsewhere. But that doesn’t mean the Taliban are our partner.