Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Ten wildcards which could decide the election

Aug 30, 2019 | Ahron Shapiro

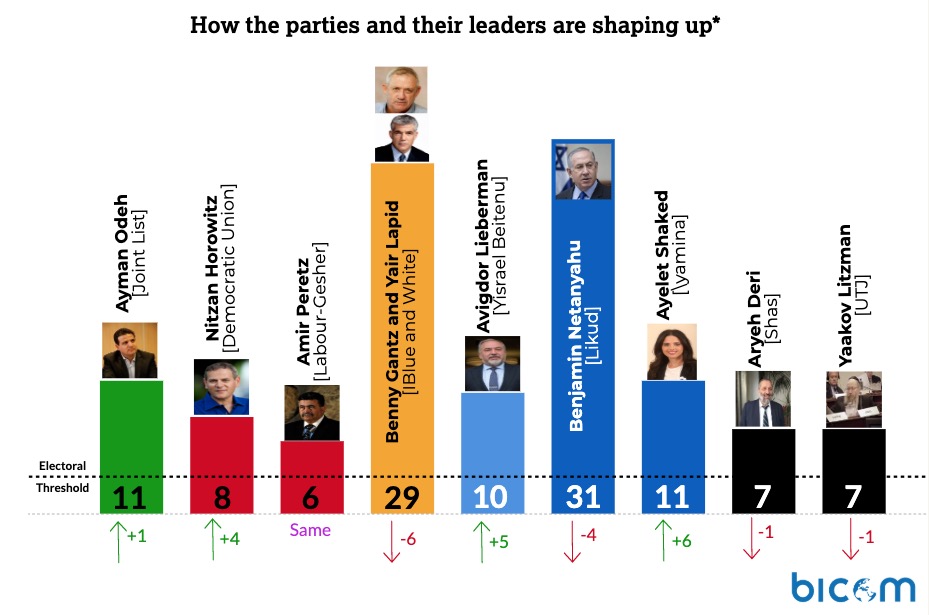

On September 17, for the first time ever, Israelis will go to elections for the second time in a year, after Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu failed to form a government following the April 9, 2019 election of the 21st Knesset.

Graphics courtesy of BICOM

Elections are always unpredictable, and all the more so in Israel. As Golda Meir famously once quipped to American President Richard Nixon, “You are the president of 150 million Americans; I am the prime minister of six million prime ministers.”

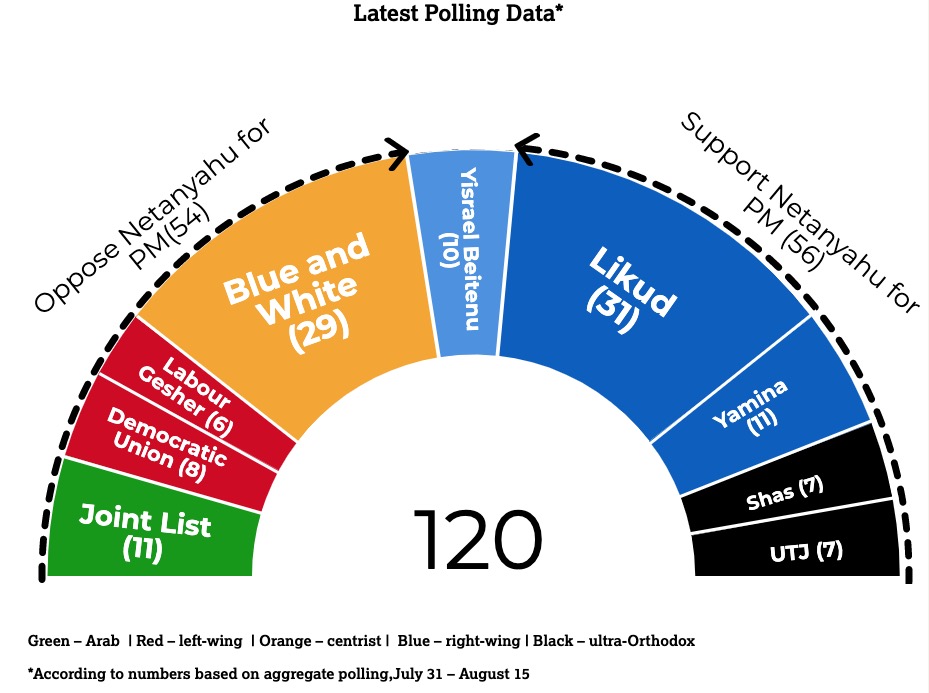

The last election in April saw Netanyahu’s centre-right Likud (“United”) and Benny Gantz’ centre-left Kachol Lavan (“Blue and White”) finish with 35 seats each in the 120-seat Knesset. Yet while the right-wing bloc carried the majority of seats, facing determined resistance from essential coalition partner Avigdor Lieberman and his five-seat Yisrael Beitenu (“Israel Our Home”) party, Netanyahu found himself unable to form a coalition and persuaded the Knesset to dissolve itself.

This unpredictable and independent spirit from someone like Lieberman, who represented only a tiny party, infuses the Israeli political process, and is part of what makes Israel’s democracy so vibrant and interesting.

While the number of variables and wildcards affecting an election are endless, I’ve compiled what I believe to be the ten largest of them for Israel in this election, in no particular order.

1. Turnout

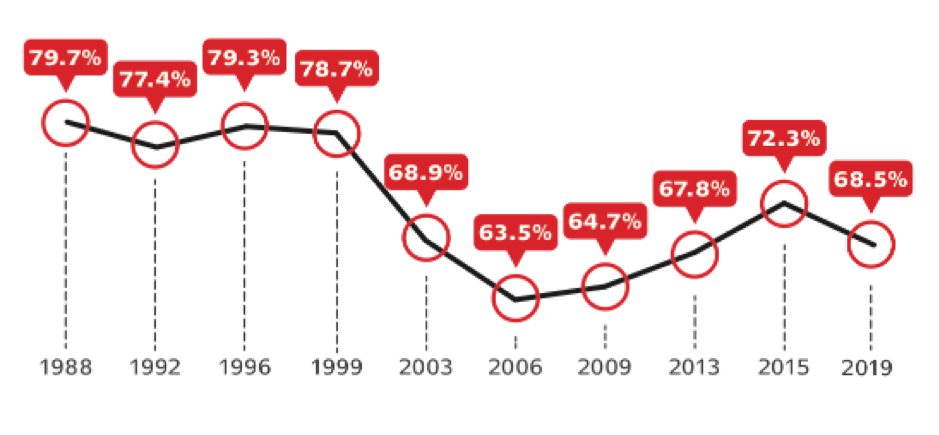

If the greatest unknown variable of April’s election was whether or not small parties would pass Israel’s 3.25% electoral threshold for entering the Knesset, the “x” factor in September’s election may well be voter turnout. Israeli voter turnout has slumped since the start of the Second Intifada in 2000, and the turnout in April’s election was particularly low with 68.5% of eligible voters participating.

Voter turnout in recent Israeli elections

The largest single reason for this phenomenon has been poor voting rates among Israel’s Arab citizens. This trend reached a low point in the last election, when only 49.2% of Israeli Arabs and Druze voted. It is estimated that 71% of the votes of those Arab voters went to the small Arab parties, but a marked increase in Arab Israeli turnout would broaden the centre-left bloc, dilute right-wing votes and increase the chances of a unity or centre-left government.

The advent of the Joint List of all Arab parties in the 2015 election saw a sharp increase in Arab participation in national elections, and there is reason to believe that the reformation of the Joint List could see the same outcome again in September.

However, any increase in Arab turnout for the Joint List could be offset should Israel’s Central Elections Committee decide to permit the use of video recording at polling stations (outside of the booths of course). The Likud has pushed for such cameras to discourage voting fraud and other irregularities – a real phenomenon in some parts of the country, with even an investigation by the left-wing newspaper Ha’aretz published on Aug. 15 finding it was a genuine problem, if not widespread. Critics argue such cameras could suppress the Arab vote. As of press time, a final decision on the camera issue had not yet been made.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have the ultra-Orthodox Jews, who are often perceived as always going to the polls in droves and voting according to the instructions of their rabbis. This perception, however, is not entirely rooted in fact. While the ultra-Orthodox do have higher voter participation rates than the general population – 73.8% in the last election – there is plenty of room for improvement. Meanwhile, it can no longer be assumed that the ultra-Orthodox who do vote will automatically choose the two ultra-Orthodox parties, United Torah Judaism (representing Ashkenzi Jews of European ancestry) and Shas (representing Sephardic Jews of Middle Eastern ancestry). About 10% actually vote for other parties and many experts believe that number is likely to increase.

In any case, voter apathy has become a major factor in every recent Israeli election, but is likely to be a particularly acute problem in this one, coming just months after the previous one. Israelis who don’t vote are a huge untapped political resource, and any bloc that can convince their followers to show up on election day in greater proportion than their adversaries will likely win the election.

2. Mergers

Lessons have been learned by Israel’s politicians since the April 9 election, where a record 47 parties vied for 120 Knesset seats, and three sizeable parties – Yamin Hadash (“New Right”), Zehut (“Identity”) and Gesher (“Bridge”) – failed to cross the electoral threshold, wasting hundreds of thousands of votes. On Sept. 17, the number of parties running has dropped to 32, and, with few exceptions, most of the smallest parties have sought strength in numbers and will run together on merged lists.

Those merged lists are, from Left to Right, the predominantly Arab Joint List (Balad, Hadash, Ta’al and the United Arab List), a revival of a successful union from the 20th Knesset elected in 2015; the Democratic Union (Meretz, the Israel Democratic Party, former Labor MK Stav Shaffir and the Green movement); and Yamina (meaning “Rightward” – comprised of Yamin Hadash, Bayit Hayehudi (“Jewish Home”) and Tkuma (“Rebirth”).

Yet beyond the practical utility of avoiding missing the electoral threshold, do mergers automatically equal better outcomes than running alone? Not necessarily.

At the end of May, Moshe Kahlon, leader of the centrist Kulanu (“All of Us”) party, accepted the Likud’s offer to absorb his four-seat party into Likud. Conventional wisdom would therefore expect to see Likud polling four seats ahead of Kachol Lavan, but most polls show the parties still running neck and neck and the Likud likely getting fewer seats than it received in April. Where did Kulanu’s voters go? Evidently, somewhere else.

Simply put, the political bedfellows that mergers create can sometimes create added value, but can also have a negligible effect or even push voters away. The Joint List has a proven record of spurring Arab turnout, and the mergers mean that Yamin Hadash and Gesher now have no reason to fear failing to cross the electoral threshold. However, beyond that, it’s anyone’s guess whether the other mergers will actually gain votes for the parties that have entered into them.

3. New leadership

April’s election saw voters coalesce around the two largest parties, Likud and Blue and White, and abandon the mid-sized parties, leaving no other party larger than eight seats. Most of these small parties have changed their leadership since April in the hope of attracting new voters – the exceptions being the ultra-Orthodox parties which were pleased with their result, the relatively stagnant Arab parties, and Lieberman’s self-styled Yisrael Beitenu. Labor replaced Avi Gabbay with Amir Peretz, Meretz replaced Tamar Zandberg with Nitzan Horowitz, and the Union of Right Wing Party’s Rafi Peretz and Yamin Hadash’s Naftali Bennett have yielded to Ayelet Shaked in the new joint venture Yamina. How effectively these new leaders capture the hearts and minds of potential voters will soon be put to the test.

4. Women

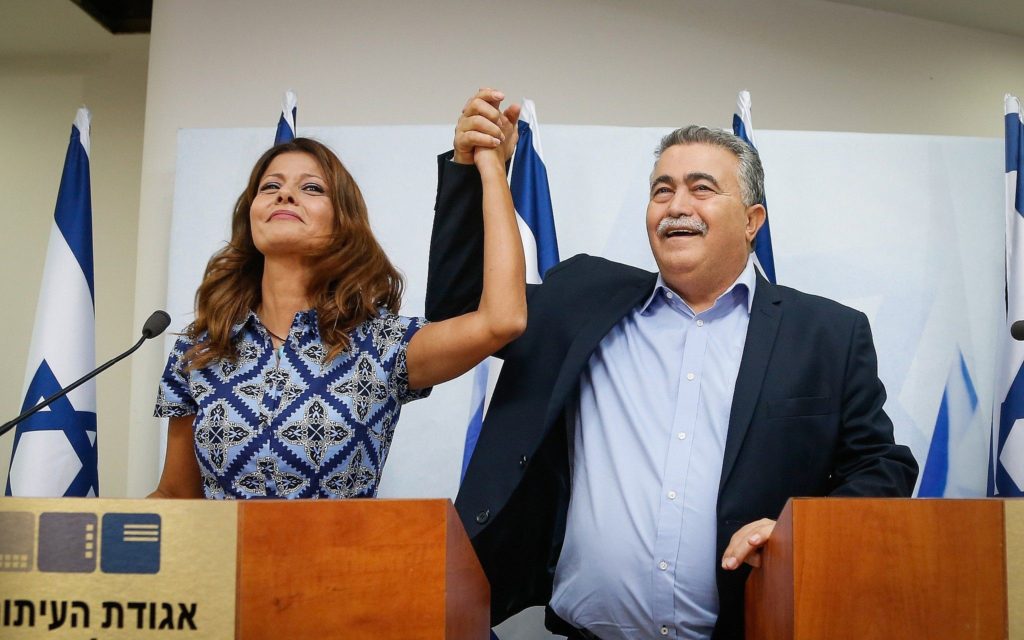

Labor leader Amir Peretz (right) with his new number 2, Orly Levy-Abecasis, following a merger with her Gesher party

In the past two elections, 29 women were elected to the Knesset (due to MKs who quit mid-term and were replaced, the 20th Knesset elected in 2015 eventually reached a record 35 female MKs). According to current polls, 33 women are likely to be elected to the next Knesset. While this is welcome news, the bigger story is not only the number of women in the Knesset, but their increasing prominence.

As previously mentioned, Ayelet Shaked, having run in second position on the New Right party list and missing getting into the 21st Knesset by the slimmest of margins, has been tapped to lead Yamina. Shaked is not only the first secular woman to lead a list that includes the Orthodox National Religious Party, she is also positioned to be the most successful woman to lead any Israeli political party since Tzipi Livni ran Kadima in 2008.

Meanwhile, following a disappointing loss in a three-way Labor leadership race, Stav Shaffir has been parachuted into the second spot on the Democratic Camp’s list, second only to Meretz’ Nitzan Horowitz, ahead of the likes of popular retired IDF general Yair Golan and former prime minister Ehud Barak – arguably the biggest drawcard for that merged party.

Similarly, Orly Levy-Abecasis, whose social-justice-oriented party Gesher took home nearly 75,000 votes in April but failed to cross the electoral threshold, is running as a joint list together with Amir Peretz’s Labor, infusing the combined party with new energy. Securely positioned in second place at Labor-Gesher, Levy-Abecasis is all but certain to assume a prominent and influential role in the next Knesset.

As election day approaches, the significance of having these women shift into leadership roles in three merged parties is sure to impact the outcome of the election in ways that are impossible to predict.

5. Hamas

In 1996, elections were held on May 29. Going into the last week of February, Labor’s prime minister Shimon Peres held a commanding double-digit lead over the Likud candidate, an untested Binyamin Netanyahu. That Feb. 25, however, a pair of Hamas suicide bombings in Jerusalem and Ashkelon killed 28 people. Polls taken just four days apart, before and after the bombing, showed Netanyahu narrowing the gap from 15 points to three, with six percent undecided.

It was a momentum shift from which Peres never recovered. In a direct vote for prime minister, Netanyahu beat Peres by almost 30,000 votes and an otherwise evenly-divided Knesset produced Netanyahu’s first centre-right government.

Fast-forward to today – in the event that Hamas decides to heat up the border region known as the Gaza envelope with a last-minute escalation in rocket attacks, would it make voters more likely to re-elect Netanyahu? Or alternatively, might it spur them to choose Blue and White’s virtual shadow security cabinet comprised of three former IDF chiefs of staff – Benny Gantz, Moshe Ya’alon and Gabi Ashkenazi – or perhaps the Democratic Camp’s Ehud Barak and former deputy chief of staff Yair Golan, or even the tough-talking former defence minister Avigdor Lieberman?

6. Voter priorities

In 2003, the secularist Shinui party won 15 seats and Ariel Sharon formed a government without ultra-Orthodox parties. This was an anomaly, as ultra-Orthodox parties have been part of virtually every coalition in Israeli history (even if ultra-Orthodox parties are not Zionist).

Since then, the issue has ebbed and flowed, but friction between the ultra-Orthodox and the rest of Israel’s Jewish society has continued to bubble under the surface. The demand by ultra-Orthodox parties to maintain the status quo regarding the drafting of yeshiva students into the IDF was Lieberman’s pretext for preventing the formation of a Netanyahu-led government after the April poll and forcing new elections.

A week after the last election, a telephone poll of 600 Israeli Jews found 66% preferred a unity government with Likud and Blue and White but without the ultra-Orthodox parties. To what extent this particular sentiment guides voter priorities will have a major impact on Sept. 17.

7. The Lieberman factor

In light of the above, Lieberman is on the record calling for a government without the ultra-Orthodox to solve the draft issue. Riding a wave of support from secular Israelis – especially, but not limited to right-wingers – Lieberman’s party is likely to double its representation in the 22nd Knesset, according to virtually all polls. Under such circumstances, Lieberman looks, by every indication, set to be the kingmaker following the election.

Lieberman has refused to guarantee support for Netanyahu, and where he throws his support might decide the composition of the next government or even potentially lead to yet another election.

8. Own goals

Since the last election, numerous politicians have made blunders big and small. Examples include: Netanyahu’s breaking of his promise not to ask potential coalition partners to support actions that could help him avoid being indicted over corruption charges; Yemina Education Minister Peretz’s comments in support of “conversion therapy” for homosexuals, his fellow party minister Betzalel Smotrich’s comments that he aspired for Israel to be a state guided by Jewish law; and a social media post by Blue and White’s Yair Lapid bashing the ultra-Orthodox. The list grows daily. Will voters punish these party leaders for exercising poor judgment?

9. Campaign finance

Moshe Feiglin of Zehut: Refused Likud offer to pay his debts

The last election left most parties in debt and ill-prepared to pay for another round of the wall-to-wall marketing that a successful country-wide campaign requires. This could be to the advantage of those parties in relatively better fiscal positions. For example, according to Israel’s Channel 13, in early August Prime Minister Netanyahu reportedly offered to pay off the campaign debt of Zehut party leader Moshe Feiglin totalling NIS 3 million (A$1.25m) if he agreed to withdraw his party from the race – a move that would have improved Likud’s chances of winning overall (Feiglin declined).

Ha’aretz reported in April that Labor was NIS 4 million in debt (A$1.67m). The paper also found that the financial position of Likud and Blue and White was much better.

However, this was the situation after the last election. Most of the spending for September’s election in the form of commercials, posters and leaflets, not to mention advisors and canvassers, will only be spent in late August and early September. As the biggest parties ramp up their campaigns, will the smaller parties have the resources to keep up, and how will that affect the election outcome?

10. Allegations of corruption

Israel has a very good track record in policing and rooting out corruption in its political ranks. Some would argue the police are almost too vigilant: in several high-profile cases, initial investigations have come up empty. That said, the number of Israeli politicians currently under investigation for corruption is alarmingly high. Besides the ongoing investigations of Netanyahu himself in three separate cases, unrelated investigations are underway against numerous politicians from parties inside and outside of government, including Likud’s Haim Katz, UTJ’s Ya’akov Litzman, Shas’ Aryeh Deri, even former Balad MK Haneen Zoabi. While it’s important to stress that all these people are presumed innocent until proven guilty, it’s not a good look. Moreover, looking back on history, Israeli voters have replaced governments over far less, and any party tainted by such allegations is at risk of a harsh judgement by voters, before they ever reach the courts.