Australia/Israel Review

Mission “Metro”

Dec 15, 2021 | Yaakov Katz

Inside an unprecedented IDF operation

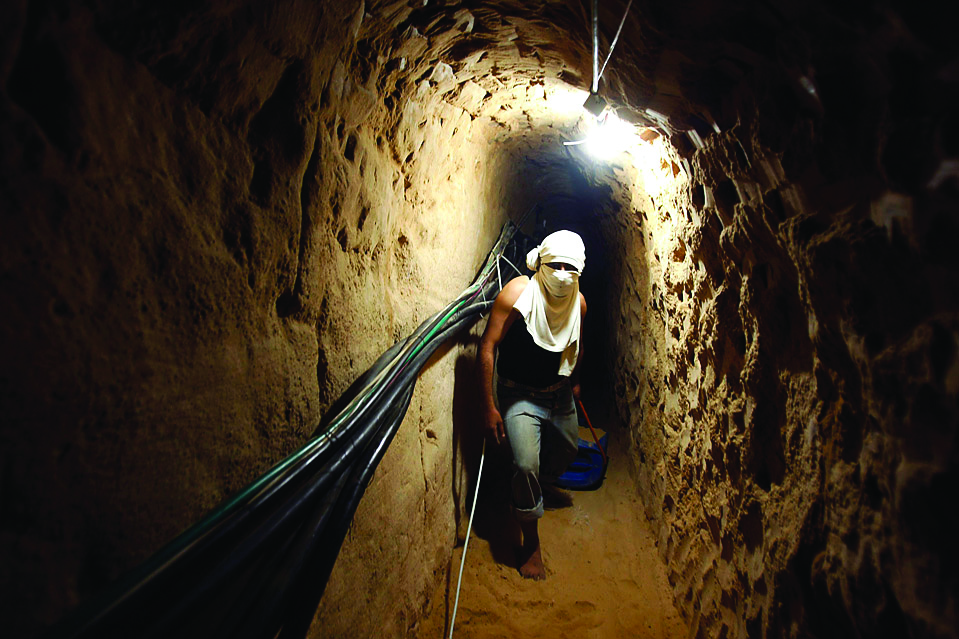

The tunnels were dug by hand and with jackhammers, as heavy machinery was out of the question – it would have attracted too much attention from the drones constantly hovering in the skies above.

Every battalion had its assignment and was responsible for the burrowing in its area of operations. Budgets were allocated according to a detailed plan, and deadlines were set for each stage of the project.

Supervising it all was Mohammed Deif, the elusive Hamas commander who became legendary for surviving numerous Israeli assassination attempts spanning more than two decades. According to some estimates, the entire project cost over NIS 1 billion (~A$446 million).

It all started seven years ago, as part of the lessons Hamas learned from the Gaza war of the summer of 2014, known in Israel as “Operation Protective Edge”. Hamas was effective using some of its underground tunnels to sneak across the border and kill soldiers, but for the most part the underground passageways were uncovered and destroyed. Hamas needed a new capability that could alter the balance of power with Israel.

Deif’s tunnels were supposed to do the job.

The idea was grandiose but also simple. Spanning around 100 km beneath almost the entire Gaza Strip, the tunnel network consisted of three different kinds of spaces: passageways to get from one point to the other; places to sleep, eat and even shower; and spaces for launching rockets. The entire network was designed to quickly and covertly move gunmen so they could surprise and attack invading Israeli infantry troops and armoured forces.

The network was a far cry from the old makeshift tunnels Palestinians once used to smuggle weapons and contraband under the border with Egypt.

“It was an underground city,” explained one senior IDF officer. “It was supposed to be their most protected weapon.”

But 2014 was also a turning point for the IDF in its battle against these underground systems. After Hamas fighters successfully infiltrated Israel, the military understood that it was far behind in the capabilities it needed. It immediately launched three simultaneous efforts.

The first was on the intelligence level – hunting for tunnels and mapping them out to the smallest detail; the second was investing resources in developing a system that could detect the tunnels as they were being dug, something like an Iron Dome for tunnels; and the third effort was in developing attack capabilities that could then destroy the tunnels.

“When attacking a tunnel, you don’t only need maximum precision,” explained Air Force Brig.-Gen. Matan Adin, commander of the Israeli Air Forces’s (IAF) Air Support and Helicopter Division. “You also need munitions that will penetrate the ground, since if they detonate on the ground, then you essentially did nothing.”

The IDF and the Shin Bet (Israel Security Agency) invested unprecedented resources in gleaning as much information as they could about the tunnel network. After a few months it was named the “Metro” by one of the officers in Military Intelligence.

Aerial surveillance was helpful but could not provide information on the routes underground. Cellular reception was also not helpful, since once underground, all reception was lost and the people inside could not be tracked.

This left the Shin Bet to focus on old-school intelligence-gathering tactics – recruiting agents and spies within Gaza who could reveal details about the routes of the tunnels and what exactly they contained.

The tunnels became an obsession for Israel. Intelligence showed that Hamas battalions were already training inside them. The terrorist operatives stored their weapons there and knew the different routes, the different exits and how to move quietly in and out.

In an effort to prevent the plans from leaking out, the Hamas battalions in the beginning were allowed to enter only their regional sections, without knowing how to cross to other areas. Hamas commanders knew that Israel would be watching. If someone was going to leak something, it wanted as much as possible to contain the damage.

Gaza is one of the most carefully scrutinised pieces of land in the world, not only surrounded by cameras on the border fence but also constantly patrolled in the skies above. Every suspicious movement is carefully tracked. Unmanned aircraft are referred to as zenana, local slang for the buzzing of a mosquito, due to the monotonous humming sound the drones’ engines make when flying in the skies above.

The precise information Israel had gathered varied. In some cases, Israeli intelligence was able to draw an exact picture of a section of the network, learning from its sources what weapons were stored there, where they were, the type of communication network, and on which wall TV screens hung. For other sections, all it had was the route but nothing more.

The Israeli Air Force preparing for missions in Gaza earlier this year (Source: IDF)

The IDF plan was in place by 2018, a joint operation planned within the IDF Southern Command – responsible for the Gaza Strip – and IAF headquarters in Tel Aviv. Due to the size of the network and the need to surprise the enemy, the initial operational requirement spoke of the need for more than 100 aircraft that would drop more than 500 bombs within the span of less than 30 minutes. It was the kind of operation not seen before in the Gaza Strip.

In November 2018, a covert IDF operation in the southern Gaza Strip went awry. Israeli commandos on an intelligence-gathering operation raised suspicion at a Hamas checkpoint. In the ensuing gunfight, Lt.-Col. M. – a decorated officer whose name is still banned from publication – was shot and killed. In response, Hamas fired dozens of rockets into Israel.

Then-Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu convened the Security Cabinet to discuss Israel’s response. Avigdor Lieberman, Defence Minister at the time, pushed to launch Operation “Lightning Strike,” the codename the IDF had given for the campaign to destroy the tunnels, a simulation of which he had personally overseen a few months earlier.

The IDF brass resisted. It was in the final stages of preparing a manoeuvre to destroy a series of cross-border tunnels that Hezbollah had dug along Israel’s border with Lebanon. Within Military Intelligence, there were concerns that launching “Lightning Strike” now could lead to a longer and larger conflict with Gaza, which would force the IDF to postpone the operation against Hezbollah’s tunnels – and the longer it waited, the greater the chance that something would leak out.

The Cabinet sided with the IDF, and “Lightning Strike” was put on ice. Upset over the Government’s weak response to the Gaza rocket fire, Lieberman resigned from the Cabinet, eventually leading to the disintegration of the Government and the first of what would turn into four consecutive elections.

In the years since, the Southern Command continued honing the operation with new intelligence constantly provided by the Shin Bet. When “Operation Guardian of the Walls” broke out in May 2021, “Lightning Strike” was put back on the table. Some generals were still hesitant, feeling that such a bombing needed to be saved for an operation whose objective was to topple Hamas. That is not what “Guardian of the Walls” was planned for.

OC Southern Command Maj.-Gen. Eliezer Toledano believed it needed to be launched. If not, he warned, it might not be relevant in a future operation. Chief of Staff Lt.-Gen. Aviv Kohavi agreed.

“Even if we don’t kill hundreds of terrorists, it is still worth setting back Hamas by 10 years,” Toledano was later quoted as saying.

That is how just after midnight on May 14, 160 IAF fighter jets took off and headed out to the Mediterranean Sea. The planes – F-15s and F-16s – were loaded with GPS-guided bombs, many of them GBU-39s, also known as the Small Diameter Bomb, a weapon made by Boeing that is small, accurate and has the ability to penetrate steel-reinforced concrete. Since they are relatively small, Israel’s F-15Is – known by their Hebrew name Ra’am (Thunder) – can carry 20 SDBs on their wings and fuselage. In Hebrew, the SDBs are called “Lethal Hail”.

It was the largest and most complicated IAF sortie since the Six Day War, when almost all of Israel’s fleet took off to destroy Egypt and Syria’s air forces in the opening salvo of that conflict.

But on this night Israel wasn’t going after an enemy air force. It was looking to take out Hamas’s prized possession – the secret weapon it had skilfully and secretly built up over a period of almost a decade.

The challenge was huge. Not only was it a painstaking effort to discover the exact route, but the IAF also had to figure out how to destroy the tunnels without toppling entire neighbourhoods: the tunnels were not under empty fields but under apartment buildings and peoples’ homes.

Israel needed to attack in a way that would on the one hand destroy the tunnels but also be so accurate that it would leave the least amount of collateral damage and not undermine the greater war effort of weakening and delegitimising Hamas.

Attacking such a small space in such a short period of time requires a level of precision and synchronisation rarely seen on the modern battlefield, especially when considering that 160 fighter jets were involved.

In many of the cases, the idea was to hit parts of the tunnels that were not adjacent to buildings, and if there was no choice, then to try to hit it on an angle.

“It was very strict planning, and everyone knew their route,” explained Lt. Ori, a 26-year-old F-16 pilot who flew that night. “We came in waves, group after group.”

The planes, which took off from different bases across Israel, gathered over the Mediterranean and waited there for the green light. Once they got it, the attack began. Every group of planes had preinstalled the GPS coordinates of their targets. The planes didn’t even have to fly over Gaza. They were able to drop their munition while still over the water.

The mission took just 23 minutes.

As Ori later explained, the challenge wasn’t the attack but synchronising the different sorties.

“The difficulty was the planning and ensuring that everyone took off on time and got to where they needed to be,” he said.

Five hundred bombs were dropped that night over the so-called Metro. While the attacks were carried out by fighter jets, drones that flew high above Gaza transmitted images back to IAF headquarters in Tel Aviv so officers there could immediately assess the extent of the damage caused.

Palestinians reported that at least 42 people were killed, some inside the tunnels and others in a couple of buildings that collapsed because of the destruction. How many of the dead were affiliated with terrorist organisations – Hamas or Islamic Jihad – was not immediately clear.

Given that Israel attacked at least 1,500 targets in densely populated Gaza, it is actually remarkable how few civilian casualties occurred (Credit: Shutterstock)

Weeks later, research conducted by the Meir Amit Terrorism and Information Centre in Israel – a think tank closely affiliated with security agencies – showed that out of the 236 Palestinians killed during the entire operation in Israeli attacks, at least 114 of them belonged to terrorist organisations. The IDF put that number even higher, claiming that close to 200 of the dead were known terrorists.

Before we break this down, an important statement: every civilian life lost in war is a tragedy, but there is a question of responsibility that needs to be addressed.

Palestinians argue that Israel is the side attacking and dropping the weapons. As a result, they say, it is Israel that is responsible.

Israel argues that Hamas intentionally stores its weapons and builds its command centres inside civilian infrastructure; and while Israel goes to great lengths to minimise collateral damage, it cannot ensure that there will not be civilian casualties.

The Metro is a case in point. That 500 bombs were dropped on a small space in such a short amount of time and “only” 42 people were killed – at least half of them terrorists according to Israel – is unprecedented in the history of war.

This was not done easily. Though intelligence revealed the tunnel network’s course, Israel could not just drop bombs along the route. That not only would have toppled dozens of buildings – it would have killed thousands of civilians.

Instead, what Israel did was astounding. It knew exactly how to hit the corner of a tunnel at a street intersection, having analysed precisely how many bombs and pounds of explosives would be needed so the explosion would have a greater effect underground and not above. When buildings did fall, it was because the collapse of the tunnel led to a collapse of the building. The structures themselves were not attacked.

“Considering the number of bombs that were dropped, it could have been much worse,” explained one senior IDF officer involved in planning the operation. “Had we done what Hamas wanted, we would have had thousands of dead civilians.”

When looking at the entire operation, that accomplishment is even more impressive. Israel attacked over 1,500 targets throughout 11 days of fighting. That is at least 1,500 bombs that were dropped on targets – and in many cases more than one bomb was used on a target to ensure they were destroyed.

Considering that Gaza, with its mere 365 square kilometres, is one of the most densely populated places in the world, the operation was an impressive achievement – and a testament to the way Israel operates and the measures it has in place to minimise civilian casualties.

While the world tends to look at this conflict through the dry and simple numbers of a scorecard – how many are dead in Gaza (more) compared with how many are dead in Israel (less) – this is a distorted perspective.

It should instead evaluate what exactly happened during the operation – the most accurate and precise military operation of this scale in modern military history.

Think about it: more than 1,500 bombs dropped in Gaza, on 1,500 targets – and maybe 60 civilians killed. That is something that has never been done before.

This does not mean the IDF did not make mistakes. Just as all wars include collateral damage, all wars include mistakes. But when looking at dry numbers, as the international community likes to do, what the IDF did in May is an unprecedented military accomplishment.