Australia/Israel Review

March Madness in Israel

Mar 29, 2018 | Amotz Asa-El

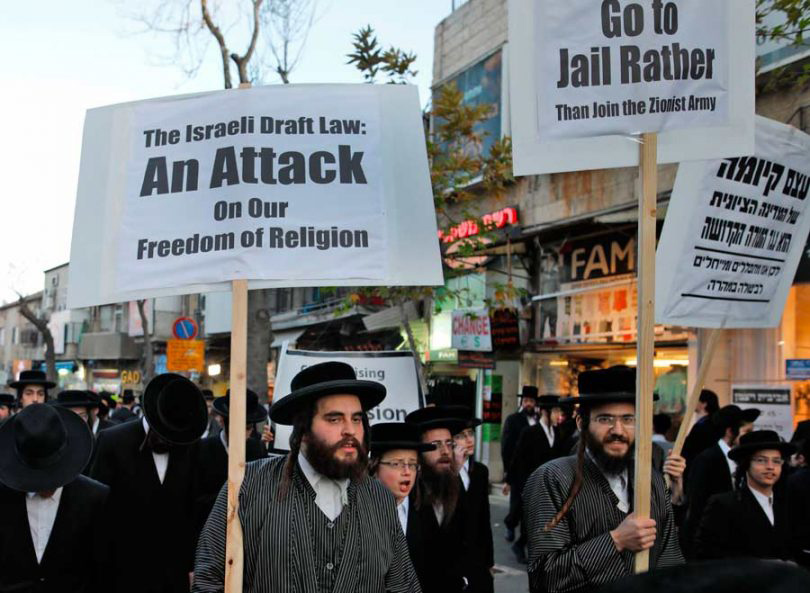

“An early election seems inevitable,” Israel’s most watched daily TV news bulletin reported on March 11. The political crisis that was gripping Israel at that time centred on ultra-Orthodox politicians threatening to bolt Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition unless the Conscription Law was amended so that more military-service deferments can be handed out to ultra-Orthodox men.

For the following three days, Israelis believed they would be going to the polls in June, 16 months ahead of the next general election’s scheduled date of Nov. 5, 2019.

By Wednesday it turned out that talk of an early election was premature. Then again, while the mechanics of the political threat and its failure were clear, the motivations that drove the disparate actors in this 72-hour political drama are fraught with contradictions and hidden meanings, and thus will continue to make the tenure of the government volatile.

The threat was ostensibly about a clash between Netanyahu’s religious and secular allies.

On the one side stood a faction within the ultra-Orthodox camp, the Gur Hassidim, whose parliamentary representative, Deputy Health Minister Yaakov Litzman, had climbed out on a political limb over the Conscription Law amendment issue. This was a priority others in his own party, United Torah Judaism, did not share, particularly as a pretext for bringing down the Government and sparking an early election.

On the other side loomed Defence Minister Avigdor Lieberman, whose five-lawmaker Yisrael Beytenu party depends heavily on the votes of Russian-speaking secular Israelis. Lieberman said that if the Knesset were to amend the existing Conscription Law, he would bolt the coalition.

Lieberman’s departure would still have left Netanyahu with a bare majority of 61 of 120 lawmakers, but it would have been too marginal to be politically reliable.

The Hassidic sects associated with Yaakov Litzman have even fewer lawmakers – three out of the United Torah Judaism party’s total of six. However, had they resigned, the rest of the 13 ultra-Orthodox legislators across two parties might have felt compelled to follow suit, fearing they would otherwise appear compromising and half-hearted while their colleagues were militant on behalf of ultra-Orthodox interests.

The atmosphere of high stakes intensified when unsourced reports claimed Netanyahu would fire Lieberman’s party colleague, Immigration and Absorption Minister Sofa Landver, should she vote against the ultra-Orthodox conscription bill in the Knesset. (Under Israeli law, a prime minister can fire a minister who votes against the government as a lawmaker. Lieberman himself is not currently a Knesset member, having resigned to make way for another member of his faction.)

Ultimately, the early-election threat was removed when both Lieberman and his ultra-Orthodox adversaries backtracked.

The ultra-Orthodox made do with the passage of their Conscription bill in a first reading only, delaying the second and third readings which would actually make it law; Lieberman’s faction agreed not to bolt the coalition for the time being, and Netanyahu did not fire Landver even though she and the rest of Lieberman’s lawmakers voted against the bill.

The Knesset’s subsequent approval of the 2019 Budget brought the crisis to a final end, after more drama was added by a threat from Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon to resign if the Budget was not passed before Passover.

These, then, were the mechanics of a unique political showdown. Yet the motivations at play were much more complex than this narrative reveals.

On the face of it, the crisis was driven by a section of the Israeli ultra-Orthodox community that set out to reverse the trend whereby a growing number of ultra-Orthodox young men, around 2,500 annually, now enlist in the IDF, as compared to fewer than a thousand 20 years ago.

Some, however, believed the crisis was masterminded by Benjamin Netanyahu.

This speculation was further fuelled by Netanyahu’s choice to remain silent, or at least seemingly inactive, throughout most of the crisis, even as his allies sparred openly.

According to this thesis, Netanyahu wanted a snap election, so as to arrive at the polls as a suspect in a series of investigations, as he is now, rather than as the defendant indicted for one or more serious crimes that he might later become.

Legal affairs commentators are estimating that the watershed moment in this regard should arrive roughly at the end of this year, at which time Attorney-General (A-G) Avichai Mandelblit is likely to summon Netanyahu to a hearing for him to put his case why he should not be indicted.

Police have questioned Netanyahu several times since last year concerning four different affairs:

One involves gifts from a businessman, Hollywood producer Arnon Milchan, totalling a cumulative NIS 1 million (A$370,000), allegedly in return for support for tax breaks and assistance in obtaining an American visa.

Another involves an alleged deal with a publisher to get favourable coverage in return for engineering a rival paper’s reduced circulation.

A third concerns alleged irregularities in the tender procedures while purchasing submarines from Germany.

A fourth alleges commercial favouritism for telecom giant Bezeq in return for favourable coverage on a news website it owns.

Israeli Police have concluded their investigation into the first of these four cases, issuing findings to the A-G recommending he indict Netanyahu.

Meanwhile, police have enlisted three former Netanyahu confidantes as state witnesses against him: former director of the Communications Ministry Shlomo Filber; former media adviser Nir Hefetz; and the Prime Minister’s former Chief of Staff Ari Harow. The three are reportedly set to testify against Netanyahu, separately, about the other three affairs.

This, in brief, is why analysts expect Netanyahu’s legal situation to produce at least some indictments.

At the same time, polls indicate that Netanyahu’s electorate remains solidly behind him, in contrast to his predecessor Ehud Olmert’s situation back when police investigated him over corruption allegations last decade.

Netanyahu’s insistence that he is the victim of a smear campaign led by the media, police, and the judiciary seems to be accepted by the hardcore electorate that helped bring him three consecutive victories since 2009 – as well as a fourth back in 1996.

Others, while not necessarily buying Netanyahu’s rhetoric, nonetheless downplay the allegations against him and say they do not justify his replacement.

Polls also indicate that Netanyahu – Israel’s longest-serving PM since David Ben-Gurion – remains by far the favoured candidate for prime minister. Thirty six percent of Israelis continue to pick him as “the most suited to head the government,” three times as many as the next most popular candidate, Yesh Atid party leader and former Finance Minister Yair Lapid.

It is this popularity that a defiant Netanyahu allegedly hoped to exploit in an early election.

To what extent such a calculation underpinned the recent crisis, and how it related to the ultra-Orthodox agenda that ignited it, is anyone’s guess. What takes no guessing is this popularity’s effect on most of the other protagonists in the March early election crisis.

The crisis exposed both Netanyahu’s rivals and allies as equally fearful of an early election.

This explains why Bayit Yehudi party leader and Education Minister Naphtali Bennett’s stance all through the crisis was that an early election was contrary to the national interest. Some analysts argued that Bennett was concerned some of his voters might migrate to the beleaguered Netanyahu in an early poll.

Stepping into the void created by Netanyahu’s passivity as the crisis unfolded, Bennett and his party colleague Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked mediated between Lieberman and the ultra-Orthodox.

Lieberman, for his part, staged his retreat the morning after polls showed his party would likely lose votes, and in fact might not pass the 3.25% electoral threshold, suggesting some of his electorate also might prefer to vote for an embattled Netanyahu rather than for the militantly secular Lieberman.

Paradoxically, a similar concern gripped the opposition Labor party.

While Labor party leader Avi Gabbay emphatically backed the idea of a June election, most of his party colleagues opposed the idea, arguing that the legal system interest demanded that an election not be held before Netanyahu is indicted.

The argument left many unconvinced, including the stridently anti-Netanyahu newspaper Haaretz, which suggested in an editorial that Labor has avoided calling for a June election not because it cared about the legal system but because it feared a trouncing.

The current Knesset thus looks likely to survive for a good ten more months at least. Having said this, an indictment might indeed dissolve it prematurely.

“Netanyahu will not be able to remain prime minister if he is indicted,” Finance Minister Kahlon said on TV in the aftermath of what has come to be called the “Conscription Bill crisis”.

As leader of the centre-right Kulanu party, a key part of the government, Kahlon’s statement is designed not to analyse events, but to shape them.

Kahlon commands ten Knesset seats and is therefore in a position to pull the parliamentary rug out from under Netanyahu’s feet whenever he decides to do so. It follows that, as things are currently proceeding, Israel will likely go to an early election in about a year, assuming that Netanyahu is indeed indicted on at least one charge. However, it is not at all safe to assume that even such challenging circumstances will result in his electoral defeat.

Tags: Israel