Australia/Israel Review

Hezbollah’s calculated gamble over gas rights

Aug 3, 2022 | Amos Harel

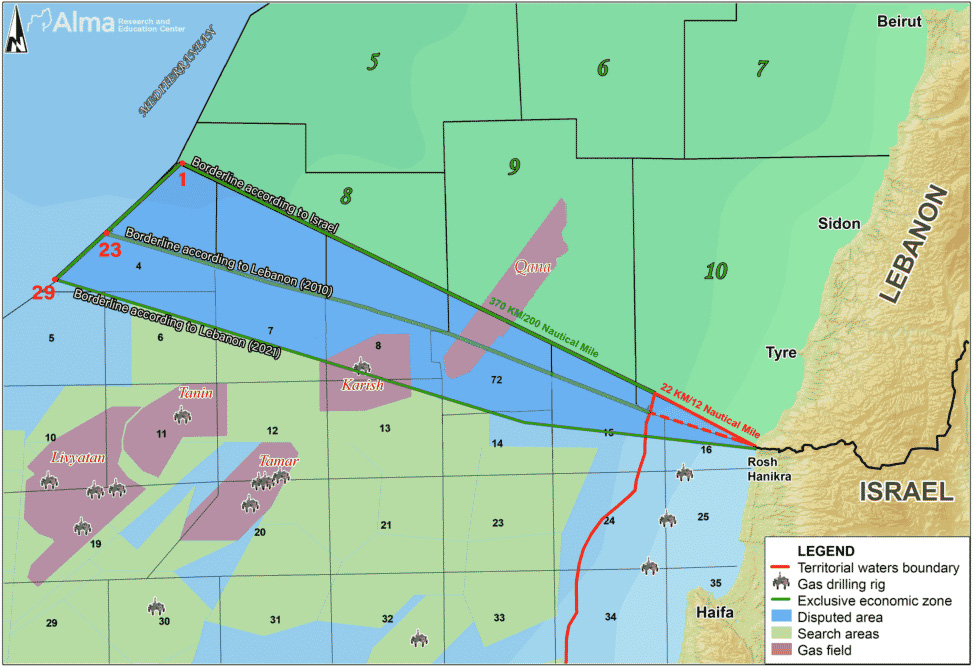

Israelis might not yet completely feel it, but their political and military leaders have recently shifted their attention to the north. The danger of an escalation with Lebanon over natural gas reserves in the Mediterranean has increased significantly.

Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah has found a new axe to grind – the demarcation of the Israel-Lebanon maritime border – and looks like he has no intention of letting up.

Very quietly, the Israeli energy industry has been putting out feelers for alternatives to the drilling at the Karish site that was planned for September, for fear it will be disrupted by the tension. The intelligence community, however, is reiterating that the danger of an all-out war with Hezbollah remains low.

A senior Israeli officer was recently asked about his confidence in these forecasts. On the face of it, he replied, Lebanon’s political morass and woeful economy should deter Nasrallah from taking action.

But Hezbollah’s shock kidnapping of two Israeli reservists in 2006, triggering the Second Lebanon War, remains a searing memory. “On July 11, a day before the war, we didn’t have a clue,” the officer said. “Looking back, I would have given a lot for us to have had just one day to prepare.”

The intelligence community admits that the picture has become more complicated since then. Hezbollah had been floating threats at varying intensities for a few weeks, but around noon on July 2 this year, something happened, or maybe three somethings.

Hezbollah launched three drones to photograph the Karish rig in Israeli waters just south of the Lebanese border (though the border’s exact location is in dispute with Hezbollah). The air force and navy shot down the drones and later announced that it had downed another drone a few days earlier.

The incident ended without casualties, but it was no minor affair. Compared to the years following the 2006 war, events are occuring at the border, and at a quicker pace. And when economic assets worth billions of dollars enter the picture, the size of the gamble also rises.

On July 13, Nasrallah threatened to disrupt the start of the drilling at Karish if an agreement on the border isn’t reached by September with US mediation. He added that Lebanon could disrupt gas supply to Europe.

That’s a significant point considering the implications of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Not only have the prices of oil and gas surged, but Russia is threatening to reduce or even halt its supply to Europe this winter as punishment for the continent’s support for Ukraine. EU officials who visited Israel in June admitted that they see Israeli gas as one of the alternatives to count on in the future.

A few days later, in private remarks that were leaked, Nasrallah warned that “things are liable to deteriorate into a war with Israel if it doesn’t let Lebanon receive its rights and extract gas from the water. We’re adopting a hard line: There will be no [gas] production in the whole Zionist entity if Lebanon doesn’t get what’s coming to it.”

At the same time, it’s important to note that Hezbollah’s drones were taking pictures; explosives weren’t attached. For now, Hezbollah’s preferred method is psychological warfare; the aim doesn’t seem to be war but rather a good agreement on the maritime border. Nasrallah is hedging the risk.

In response, the Israeli leadership, which released few statements following the downing of the drones, sharpened its tone. Prime Minister Yair Lapid and Defence Minister Benny Gantz visited the Northern Command together and warned Hezbollah not to harm Israel’s gas assets.

Lapid then flew over the rig. His office released a photo of him viewing Karish from a helicopter, with a quote attached that makes clear that the gas might be exported to Europe and Egypt.

Gantz had flown to the rig about a week before Lapid. His office didn’t publish a photo; the military believed that a picture of the minister there would erroneously send the message that Israel is concerned about Nasrallah’s threats. Lapid acted differently.

According to the intelligence analysis, Nasrallah hasn’t changed his mind: He’s still flinching from war – the scars of 2006 remain fresh in his memory, too.

Nasrallah is basically considered the most experienced and responsible leader in the region – against the backdrop of the damage that Hezbollah suffered in the 2006 war – which was also extremely frustrating for Israel. Still, Nasrallah is under attack in Lebanon over the organisation’s refusal to disarm.

Controlled friction with Israel over the gas reserves could provide justification for continued military resistance, especially if it ends with Israel capitulating and the border delineated in a way that gives greater gas reserves to Lebanon.

Military intelligence sees the frequent declarations as a calculated gamble: Nasrallah is trying to extort concessions that will be credited to Hezbollah by the Lebanese people, now groaning under electricity and water shortages. At the same time, he’s being careful to avoid a head-on collision.

Still, a dynamic of escalation has been unleashed. With each side responding to a growing threat from the adversary, it’s hard to control the process. Military Intelligence’s 2022 appraisal mentioned Lebanon as an unexpected source of bad tidings. That danger, though being managed, has become more concrete because of the gas dispute.

The preferred way out is an American demarcation of the maritime border in a way that’s acceptable to both sides. In such a case, Israel would continue to drill at Karish and Lebanon would at last be able to launch a gas project north of the border.

But the US mediator, Amos Hochstein, who visited Israel in mid-July, didn’t bring good news. His Israeli interlocutors got the impression that the talks have hit a dead end.

That’s apparently the backdrop to the feelers being put out by the energy companies. According to the original plan, the start of drilling at Karish was supposed to enable the consortium that runs the Leviathan site to request authorisation to divert some of the gas to Egypt – and gain a higher price. It was recently hinted to these companies that this development might be delayed if Hezbollah heats up the sector in September.

And there’s another question. Teheran hasn’t commented on the gas affair and hasn’t joined Hezbollah’s threats. When he ordered the kidnapping of the reservists in 2006, Nasrallah acted on his own without informing the Iranians. The organisation presented the ensuing war as a victory, but it cost the Iranians part of their military investment in Hezbollah.

Iran did two things after the war. It quickly rearmed Hezbollah, this time on a far larger scale in both quantity and quality. And it deprived Nasrallah of the authority to decide on his own so as not to entangle Teheran again in a confrontation clashing with its strategic interests.

It’s hard to figure out what Iran wants this time. Will it give Hezbollah freer rein and let the organisation heat up the sector with Israel, or will it restrain Nasrallah on the grounds that the main consideration is the signing of a new nuclear agreement between Iran and the powers?

According to Shimon Shapira, a Lebanon expert at the Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs, it can’t be ruled out that Teheran is spurring Hezbollah’s threats in response to the visit to the region by US President Joe Biden and the contacts about establishing a regional air defence alliance.

Michael Young, a researcher at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, expressed similar sentiments in a recent article. In his view, the drones also sent a message to Biden: Don’t try to fence Iran in.

But other experts believe that the gas issue is too Lebanon-specific for the Iranians to dictate the tone. This story, they say, begins and ends with Nasrallah.