Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The Virtual Caliphate

Oct 10, 2017 | Mina Hamblet

Mina Hamblet

The public outcry surrounding President Trump’s attempted travel ban on people from seven radical Muslim states, designed to prevent foreign terrorists from entering the country, has diverted attention from the longstanding danger of homegrown jihadists.

As early as 2007, the New York Police Department (NYPD) released a 92-page report documenting the extent of al-Qaeda-linked homegrown jihad in Europe and the United States. The Obama Administration, however, went out of its way to ignore, deny, and whitewash any homegrown terror that smacked of Islamist violence.

But a decade later, al-Qaeda has been all but eclipsed by the Islamic State (ISIS), which has skilfully used social media to become the foremost purveyor of jihadist indoctrination in the West, creating a “virtual caliphate,” extremely dangerous and easily accessible to vulnerable men and women from a variety of backgrounds in a manner al-Qaeda was never able to achieve. Even were all territory now under ISIS control to be retaken, this virtual caliphate could continue to pose a major threat.

Cyber Radicalisation

While the NYPD’s report noted the Internet “as a driver and enabler for the process of radicalisation” for al-Qaeda, this was largely limited to the terrorist group’s use of chatrooms, which represent only a small portion of the Internet’s potential. Indeed, according to a 2011 Rand Institute study, while al-Qaeda “does 99 percent of its work on the Internet,” its scope is limited to merely a few cyber platforms, demonstrating its simplistic utilisation of the Internet. By contrast, ISIS has taken a more advanced approach, targeting and utilising a number of novel platforms to preach its jihadist ideology, thus blending tradition and technology in a sophisticated manner. Running a US$2 billion campaign thanks to its oil monopoly in Syria, the group expertly commands usage of the cyber community in a multitude of forms: Twitter is by far the platform of choice among forums such as Facebook, Google, Tumblr, Kik, WhatsApp, and more.

Coupled with its use of more under-the-radar messaging apps such as Telegram (which is encrypted) and Surespot, ISIS is able to maintain a constant and steady presence on the Internet.

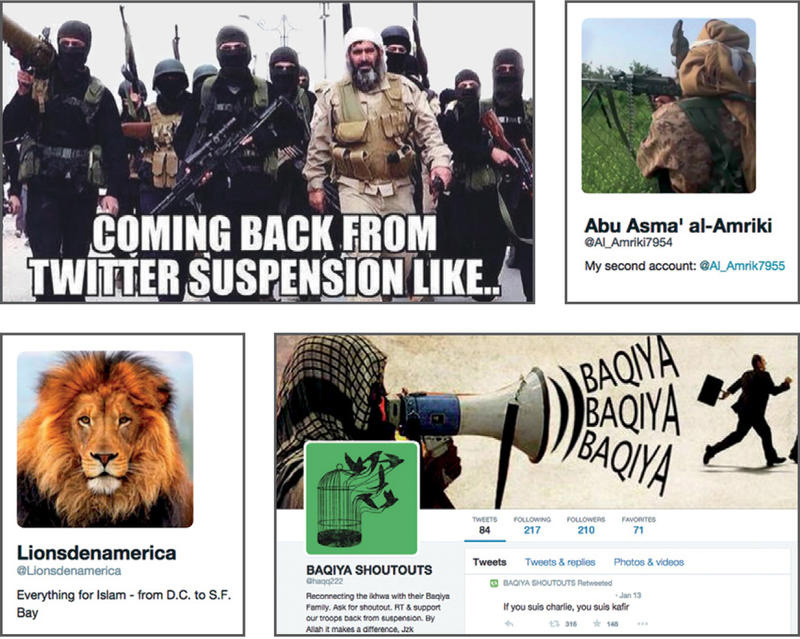

Constant accessibility. Not only is ISIS using non-traditional and innovative cyber platforms, but it is also ensuring continuous access to its content. Its supporters have found ways to outmanoeuvre Twitter’s continued closing of jihadist accounts, notably via Bait al-Ansar (literally, the House of Supporters), which allows users to recreate new accounts quickly without having to enter new information. In fact, as shown by a 2015 George Washington University study, many jihadists view account suspensions as “badges of honour”. Twitter campaigns – such as “Hashtag Jihad” – are also utilised to encourage Americans to join the fight in Syria, according to the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) Cyber and Jihad Lab. At times in 2015, the US Government was battling about 90,000 tweets a day, according to a State Department spokeswoman; and while a militant may be killed, a tweet cannot.

Highly popular sites are not the only form of jihadist communication. The more covert messaging app, Telegram, provides almost complete anonymity to its users and relies on client-server/server-client encryption, dedicates whole channels to ISIS and its ideology. “The Nasheed Gallery,” a channel on the app, allows supporters (and potential supporters) to listen to jihadi nasheeds, also known as Islamic songs. The songs are a “main factor in reinforcing the group’s narrative and attracting new recruits,” according to MEMRI. This channel and channels similar to it can be accessed anytime, granting potential supporters unlimited access to jihadist ideology.

The radicalisation echo chamber. The success of ISIS’s Twitter campaign can be attributed to its use of the platform as a “radicalisation echo chamber,” namely the sharing and spreading of jihadist propaganda for continued consumption by other supporters and, even more importantly, potential supporters. The chamber is comprised of three user groups: nodes, amplifiers, and shout-outs, and can best be understood as a tier-like system.

The nodes (first tier) are by far the loudest and most authoritative voices in the social media jihad realm, tweeting out videos, phrases, articles, etc. The amplifiers (second tier) then engage the content further by re-tweeting material from the nodes; and while not necessarily presenting new material and propaganda, they actively utilise the node twitter accounts. Finally, shout-outs (third tier) allow users to become familiar with ISIS accounts by giving them a “shout out,” or naming them in tweets, thus promoting the original node accounts, making the shout-out users “vital to the survival of the ISIS online scene.”

The average ISIS Twitter account has one thousand followers, and the echo chamber process is an integral part of ensuring the continued success of the accounts.

Resulting recruit success. By constantly capitalising on modern technology, ISIS supporters are able to continually engage the online community as “keyboard warriors”. However, the online jihad is not merely talk. Between March 2014 and November 2015, 82 people within the United States were arrested on charges related to promoting terrorism or attempting to initiate an attack. Of the 82 individuals, 39 (47.5%) had a strong social media presence prior to their interdiction.

In addition, the number of arrests made among ISIS and al-Qaeda supporters in the United States highlights the recruiting success of ISIS. A 2011 Rand Institute report identified 176 people who had been interdicted or arrested following 9/11, an average of 1.5 al-Qaeda recruits per month on American soil. On the other hand, ISIS averages 4.1 recruits per month, a 300% increase in recruitment rates over al-Qaeda.

Demographic Variances and Similarities

Analysing the recruitment rate is an integral part of measuring ISIS’ reach, but the demographics of its supporters are an equally important way to understand its success in Western radicalisation.

Although there are some similarities among individuals radicalised by al-Qaeda and ISIS, the latter group has managed to broaden the demographic base in a number of ways, a reflection of its successful social media outreach campaign. The NYPD report found most al-Qaeda supporters to be second or third generation males under the age of 35 from “Middle Eastern, North African, and South Asian cultures,” highlighting that “middle class families and students appear[ed] to provide the most fertile ground for the seeds of radicalisation.”

By contrast, most ISIS supporters are males under the age of 26, from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds and social classes. Understanding the ISIS audience highlights how the organisation is poised to continue to successfully target a young and extremely vulnerable demographic.

Age. At a quick glance, the comparative demographic overview of radicalised Western supporters from al-Qaeda and ISIS seems nearly identical, with “young and male” being the most obvious description. However, to place the supporters of both groups in the same category is to ignore the youthful trend of the Islamic State and its path across a variety of social and economic cleavages, all of which highlight the expansive success of its radicalisation tactics. Most obviously, and perhaps most importantly, the drop of supporters’ median age from 35 to 26 signals the success ISIS has in reaching a younger audience, once again a facet of its effective social media campaign. According to the Pew Research Center, 86% of people between the ages of 19 and 29 utilise social media. The decrease in average supporter age by nine years is a testament to the success of ISIS in skilfully using social media.

While many of the case studies used by the 2007 NYPD report focused on men in their thirties taking part in jihad, it is the stories of young teens fleeing their Western nations to join ISIS and their potential for exporting jihadist terrorism to the West on their return home that has dominated headlines over the past few years. This is not to say that the NYPD report inaccurately assessed the profile of al-Qaeda supporters, but rather to highlight how ISIS has expanded beyond that initial demographic to capture a larger breadth of supporters. In a 2015 briefing on the foreign terrorist threat of ISIS, US Assistant Attorney-General John Carlin noted,

“This is a social media-driven threat, in over 50 percent of the cases the defendants are 25 years or younger, and in over a third of the cases, they are 21 years or younger. And for us in confronting the terrorist threat, that is different than the demographic we saw who went to support core al-Qaida in the Afghanistan region.”

Ethnicity. Age is not the only shifting demographic. Indeed, the case studies of the NYPD report are marked by the distinguishing demographic feature of 30-something Middle Eastern men. In Madrid’s 2004 attack, London’s 2005 bombing, the attempted New York City Herald Square bombing, etc., all the perpetrators came from relatively middle class families from either the Middle East or Pakistan. The report even highlights the universities the men attended, types of families they grew up in, and even one fighter’s estimated estate worth.

By contrast, ISIS followers are “not confined to any ethnic group,” nor is their economic background the same. Supporters of ISIS represent a broad international spectrum, with some 40% being converts to Islam.

Though the list of examples is long and diverse, ultimately all of them represent a fundamental shift in demographics from specific ethnic groups to the expansion of the jihadist Western radicalisation movement. This variation of ISIS supporters attests to its success. Once again, its utilisation of social media has granted it access to a number of ethnic groups and nationalities and has contributed to diversity among foreign fighters.

The Indoctrination Process

While it is apparent that ISIS achieved (and continues to achieve) greater success than al-Qaeda in radicalising Western citizens, a comparison of the methods used by the two terror groups finds the process to be strikingly similar. The NYPD report, heavily criticised for its discussion of the pattern of indoctrination when published in 2007, holds up as a credible source for understanding the process of radicalisation when analysed next to a study of ISIS radicalisation.

The 2007 report broke new ground in publishing its analysis of both the indoctrination pattern and the spectrum of radicalisation. It highlights that, though the demographics and platforms utilised by ISIS are more successful in garnering support, the specific process an individual must complete (and the environment that triggers it) is largely the same.

Four stages to radicalisation. The NYPD report found the radicalisation process to be a clearly defined structure, with the following four distinct phases:

- Pre-radicalisation: life before adoption of Salafi jihadist ideology;

- Self-identification: exploration into Salafi Islam;

- Indoctrination: intensification of beliefs, complete adoption of ideology;

- Jihadisation: acceptance of the duty to wage jihad; planning and execution of attack.

While each phase is important in its own right, the greatest overlap for al-Qaeda and ISIS supporters occurs in the first stage: pre-radicalisation. It is in this vulnerable stage that the exploration into jihad first begins; and despite the divergent radicalisation tactics of the two terror groups, the pre-radicalised lives of their followers prove to be nearly identical, underscoring the unchanging nature of those most susceptible to jihadist indoctrination, namely individuals looking for the “meaning of life” and seeking identity. By and large, they lead ordinary lives but feel estranged from society and are motivated by an activist spirit.

This loneliness, averageness, and desire for community are some of the key catalysts for seeking jihadist propaganda, and this narrative has hardly shifted with the rise of ISIS. German researcher Daniel Koehler, who evaluated three Somali-American teens who attempted to travel to Syria, found a number of pre-radicalisation signs similar to those outlined in 2007, which he termed the “radicalisation recipe.”

A number of factors set off the process, including, “experiences of racism, bullying, lack of education. … anything that frustrates you and alienates you from your hosting society.”

These vulnerabilities provide a fertile breeding ground for al-Qaeda and ISIS recruits alike.

In later stages, such as self-identification, the ISIS recruits are driven by a certain interpretation of Islam they find compelling, which is intensified when coupled with their “warrior spirit.”

The path to radicalisation among al-Qaeda supporters is set with the same markers according to the NYPD report, which notes the presence of “activist-like commitment or responsibility to solve global political grievances through violence.”

A spectrum of threat. While the radicalisation process, especially in its earlier stages, is enticing to young people and dangerous if completed, not every potential recruiter emerges as a jihad-driven terrorist. The process acts as a funnel: At every stage, the pool of recruiters grows smaller.

Similarly, not every ISIS supporter commits to jihad. Some never manifest beyond their keyboard warrior persona while others withdraw when the moment of truth arrives (e.g., travelling to Syria or carrying out a terror attack in their Western home country). Ultimately, both spectrums for al-Qaeda and ISIS recruits tell a similar story: These supporters are the minority, not the majority, of Muslims, and embarking upon the process does not wholly commit someone to jihad.

Accessibility helps ISIS. A final note about indoctrination worth mentioning is the role of travel. In many cases, travel to Middle Eastern countries can be a powerful mechanism in strengthening jihadist ideology within a person and providing training in how to commit to jihad.

While al-Qaeda encouraged travel, and all the case studies examined by the NYPD report include individuals who traveled or attempted to travel, there are significant differences in the accessibility of these states. Afghanistan, for example, can be difficult to access, while Syria and Iraq were, until recently, easier to reach with the largest entry point being through Turkey – although the abortive July 2016 coup d’état there seems to have had a moderating impact. At least 51% of ISIS recruits since February 2014 travelled to or attempted to travel to Syria, providing greater access to its ideology and training.

Conclusion

While the process of jihadist radicalisation in the West is not unique to the twenty-first century, a comparison of the tactics used by al-Qaeda and ISIS highlights how it has rapidly evolved over a short period of time due to the introduction of new propaganda tools, most notably modern social media with its massive appeal to Western youth. Through an easily accessible social media campaign, using such platforms as Twitter, ISIS has succeeded in commanding the attention of millions. Its constant presence on the Internet has translated to greater recruitment rates than al-Qaeda, a younger demographic, and a more diverse ethnic base.

At the same time, the triggers for radicalisation and the steps leading to full jihadist indoctrination have remained virtually constant, although occurring at a speedier pace with more diverse levels. There is no single successful methodology for identifying potential perpetrators, but continuing to monitor social media while creating a cyber counter-narrative campaign may be a powerful way to dissuade the young, vulnerable minds on which ISIS so successfully preys.

Mina Hamblet served as a research intern at The Jewish Policy Center and is currently at the University of Virginia. © Middle East Quarterly (www.meforum.org/meq/), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Islamic Extremism