Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The “Nakba” Narrative

Mar 2, 2023 | Sol Stern

Its origins, history and implications

Israel will soon celebrate the 75th anniversary of its independence. Around the same time, Palestinians will stage their annual Nakba Day, the official commemoration held every year on May 15 to protest Israel’s creation. The marking of this supposed “catastrophe” (nakba) will surely be a key feature of the elite media discussion of Israel’s anniversary. As such, it will represent an ongoing public-relations triumph for the Palestinians – and a victory for deceit and disinformation.

The Nakba narrative depicts the founding of Israel as a catastrophe that resulted in the dispossession of the land’s native people. Yasser Arafat, then the President of the Palestinian Authority (PA), invented “Nakba Day” on May 15, 1998, just as Israel was celebrating its 50th anniversary. From his West Bank headquarters, Arafat read out marching orders for the day over PA radio stations and public loudspeakers:

The Nakba has thrown us out of our homes and dispersed us around the globe. Historians may search, but they will not find any nation subjugated to as much torture as ours. We are not asking for a lot. We are not asking for the moon. We are asking to close the chapter of Nakba once and for all, for the refugees to return and to build an independent Palestinian state on our land, our land, our land, just like other peoples.

Nine Palestinians were killed that day. Hundreds more (including some Israelis) have died during Nakba Day riots over the subsequent quarter century.

Yet it wasn’t the deadly violence that made the first Nakba Day historically significant. Rather, at a time when the 1993 Oslo peace accords remained in force and still offered an opportunity to achieve a “two-state solution” to the conflict, Arafat decided to weaponise the Palestinian narrative into a declaration of permanent war against Israel. The key element of his Nakba Day speech was his claim that there were five million Palestinian refugees who had a sacred “right of return” to their homes in Jaffa, Haifa, and dozens of formerly Arab cities, towns, and villages in Israel.

In three-plus decades as Palestinian leader, Arafat failed to accomplish anything constructive for his people. But Nakba Day did advance his goal of prolonging the glorious struggle against Zionism. The PA now claims there are seven million refugees. Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas, is just as adamant that the conflict must go on and on until all the refugees are granted the right to return to their former homes in Israel. Abbas even offered an updated version of the Nakba last summer when he publicly declared, in Germany, that the Palestinians had suffered the equivalent of “50 Holocausts” at the hands of the Jews.

Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Palestinians will express their rage over Israel’s existence by joining Nakba Day riots in May. We can also expect an upsurge of support for the 25th annual Nakba commemoration from the international leftist coalition that celebrates the Palestinians as unique victims of Western racism, colonialism, and Zionist perfidy. In street demonstrations and on college campuses, activists will be chanting the slogan that sums up the final goal of the Nakba narrative: “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.”

The Nakba has even entered the halls of the US House of Representatives through a resolution authored by Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib and endorsed by six of her Democratic Party colleagues. The resolution calls on the US Government to “commemorate the Nakba through official recognition and remembrance” and to “reject efforts to enlist, engage, or otherwise associate the United States Government with denial of the Nakba.”

Their fellow members of Congress need not worry about the danger of Nakba denial. The problem is the reverse. All too many perfectly sensible people, including quite a few liberal Israelis, seem willing to ignore the deadly implications of the Nakba narrative for fear of being accused of insensitivity to another people’s suffering.

If “nakba” merely means catastrophe, then the word is a fitting one. Unquestionably, Palestinians suffered a terrible human tragedy in 1948. Around 700,000 men, women, and children lost their ancestral homes, and Palestinian civil society disintegrated. The refugees dispersed to the Jordanian-occupied West Bank, the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip, and neighbouring Arab countries. Ninety percent have since passed away, but around two million of their progeny languish in dismal refugee camps. After 75 years, this giant remnant should be resettled in new housing and compensated for their losses. Resettlement is exactly how every other refugee catastrophe after World War II (including a total of 13 million refugees in Europe alone) was solved.

But the Nakba has more than one meaning. The version now promoted by Palestinian leaders and their supporters assigns exclusive blame for the 1948 catastrophe to the Jews, while proposing an absurd remedy that would mean suicide for the Jewish state.

Supporters of Israel are often asked to prove their decency by acknowledging the reality of the Nakba. There’s no reason to shrink from that challenge. What’s needed is a serious forensic examination of the various Palestinian narratives, their truths, falsehoods, and their hatreds. The place to begin that inquiry is with the very first Nakba text, published in Beirut 75 years ago.

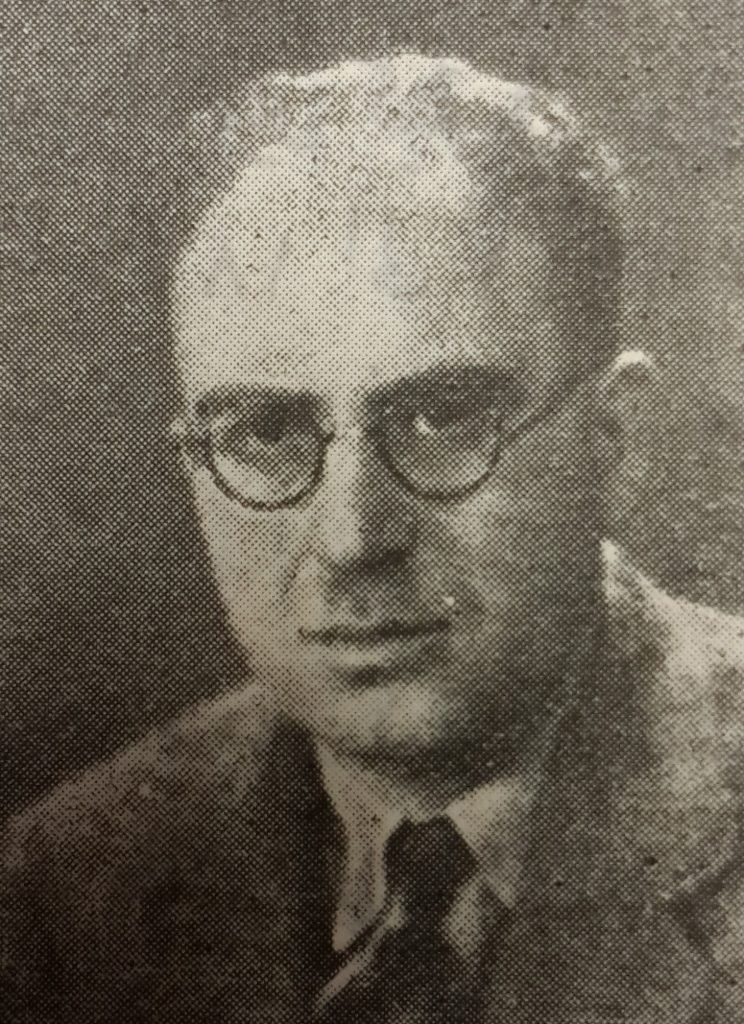

Constantine Zurayk (Image: Wikipedia)

On Aug. 5, 1948, not quite three months after the new state of Israel was invaded by five Arab armies, a short volume titled Maana al-Nakba (later translated as The Meaning of the Disaster) appeared in Beirut to popular acclaim. The author was Constantine K. Zurayk, a distinguished professor of Oriental history and Vice President of the American University of Beirut.

Zurayk was the wunderkind of the Arab academic world. Born in Damascus in 1909 to a prosperous Greek Orthodox family, he was sent off at 20 to complete his graduate studies in the United States. He then returned to Beirut and the American University.

Zurayk soon became one of the leading advocates of the liberal, secularist variant of Arab nationalism. After Syria won its independence in 1945, he was chosen to serve in the new nation’s first diplomatic mission in Washington, D.C., and also served with the Syrian delegation to the United Nations General Assembly.

Zurayk’s 70-page book reflected the sense of outrage among the Arab educated classes over the 1947 UN partition resolution and the creation of the Jewish state. It then became a reference point for future pro-Palestinian historians and writers.

In previous writings about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, I wasn’t able to comment on Zurayk’s book. It was never published in the United States. It was only recently that I found a rare copy in a university library and finally read the real thing.

It was not what I expected. The Meaning of the Disaster actually isn’t about the tragedy of the Palestinian people. According to Zurayk, the crime of the Nakba was committed against the entire Arab nation – a romantic conception of a political entity that he and his fellow Arab nationalists fervently believed in. Zurayk was no champion of an independent Palestinian state.

In an introductory paragraph, Zurayk writes about “the defeat of the Arabs in Palestine,” which he then calls “one of the harshest of the trials and tribulations with which the Arabs have been afflicted throughout their long history.” Zurayk’s only comment about Palestinian refugees is that, during the fighting, “four hundred thousand or more Arabs [were] forced to flee pell-mell from their homes.” (All italics added.)

Zurayk predicted that all Arabs would continue to be threatened by international Zionism: “The Arab nation throughout its long history has never been faced with a more serious danger than that to which it has today been exposed. The forces which the Zionists control in all parts of the world can, if they are permitted to take root in Palestine, threaten the independence of all the Arab lands.”

The Arabs also faced the immense power of Western imperialism, according to Zurayk, but this would prove merely a “temporary evil”. On the other hand, “the aim of Zionist imperialism is to exchange one country for another, and to annihilate one people so that another may be put in its place. This is imperialism, naked and fearful in its truest color and worst form.”

Zurayk not only insists that Jews have no national rights in Palestine, but he denies the historic connection between the Jewish people and the ancient land of Israel. “The Zionist Jews who are now immigrating to Palestine,” he writes, “bear absolutely no relation to the semitic Jews.” Zurayk dredges up the discredited theory that the Eastern European Jews were descended from Khazar tribes that converted to Judaism in the eighth century.

Still, Zurayk is left to wonder how the combined Arab armies, far outnumbering the Jews, could have allowed the Zionists to achieve their military objectives in Palestine. His answer is rife with antisemitic canards and conspiracy theories:

The causes of this calamity are not all attributable to the Arabs themselves. The enemy confronting them is determined, has plentiful resources, and great influence. Years, even generations, passed during which he prepared for this struggle. He extended his influence and his power to the ends of the earth. He got control over many of the sources of power within the great nations so that they were either forced into partiality toward him or submitted to him.

Zionism … is a worldwide network, well prepared scientifically and financially, which dominates the influential countries of the world.

Not content with depicting Jews as devious manipulators of power and wealth, the secularist Zurayk also ventures into the realm of theology to offer his readers a grotesque slander of Judaism. “The idea of a ‘chosen people’,” he writes, “is closer to that of Nazism than to any other idea and [in the end] it will fall and collapse just as Nazism did.”

Constantine Zurayk’s fiction that the “Arab nation” suffered the Nakba didn’t survive for long. In the June 1967 Arab–Israeli war, three Arab states again attempted to undo Zionism. When they failed and lost even more territory to Israel, the Arab coalition to destroy Israel fell apart. Two of those countries eventually signed a separate peace with the Jewish state. Pan-Arab nationalism was dead.

The meaning of the Nakba had already changed as Palestinian activists and historians began depicting the events of 1948 exclusively as a tragedy for their own people. In the mid-1950s, Aref el-Aref, a noted Palestinian journalist, historian, and mayor of east Jerusalem during the Jordanian occupation, published a six-volume history of the Palestinian struggle titled The Nakba of Jerusalem and the Lost Paradise. Many more Nakba books with an exclusively Palestinian focus were published over the next four decades.

Mural depicting Palestinian intellectual Edward Said – the most influential recent author promoting the contemporary Nakba narrative (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The most influential of those volumes, particularly for audiences in the West, was Edward W. Said’s The Question of Palestine, published in 1979. Said, a popular Columbia University English professor and a member of the Palestinian National Council, was something of an icon in liberal intellectual circles because of his earlier book, Orientalism. In that work, Said framed the history of colonialism in the Arab and Islamic world within a system of Western racialist thought.

In The Question of Palestine, the author argued that the game was stacked against the native Palestinians in favour of the white Zionists, because of the same dominant racist ideologies. Said denounced “the entrenched cultural attitude toward Palestinians deriving from age-old Western prejudices about Islam, the Arabs, and the Orient. This attitude, from which in its turn Zionism drew for its view of the Palestinians, dehumanized us, reduced us to the barely tolerated status of a nuisance.”

“Certainly, so far as the West is concerned,” Said continued, “Palestine has been a place where a relatively advanced (because European) incoming population of Jews has performed miracles of construction and civilizing and has fought brilliantly successful technical wars against what was always portrayed as a dumb, essentially repellent population of uncivilized Arab natives.”

This was a harsh and distorted view of the Zionist movement. Still, Said was somewhat constrained relative to later declarations by Palestinian leaders comparing the Nakba to the Holocaust.

What the early Nakba studies did have in common was an indictment of the Jews for dispossessing the Palestinians, while finding no fault at all on the Palestinian side. Several Israeli revisionist historians and “post-Zionist” pundits also endorsed aspects of the Nakba narrative.

Yet that narrative was rebutted by other historians of the Israel-Palestinian conflict. That is how scholarly controversies usually play out in open societies.

It is in totalitarian societies that national narratives are enforced by the ruling government. Until the mid-1990s there could not have been an officially endorsed Palestinian narrative, because the Palestinians had no governmental institutions. Ironically, it was an audacious diplomatic initiative taken by the Israeli government in pursuit of peace with the Palestinians that had the unintended effect of creating an officially approved Nakba narrative.

In January 1993, Israeli representatives made secret contacts with high-ranking officials of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in Oslo, Norway. The discussions blossomed into what became known as the Oslo process, and by September of that year, they culminated with the famous handshake on the White House lawn between Yasser Arafat and the then Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin.

At the time, Arafat was stranded in Tunis, far from Palestine and in a very precarious position. Along with his PLO cadres, he had been expelled from Jordan in 1970, thrown out of Beirut by Israel’s army in 1982 and then again kicked out of Tripoli, Lebanon, by the Syrians. Arafat’s reputation was in tatters among many Arab governments because of his decision to support Iraqi dictator Sadam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait.

In signing the Oslo Accords, the Rabin Government threw Arafat a lifeline. Political controversy later erupted in Israel and elsewhere over the wisdom and practicality of the peace agreements. For the purpose of our argument here, however, it’s sufficient to note that the document signed by Rabin and Arafat represented a fairly straightforward political deal, a quid pro quo of sorts.

Arafat was rescued from his Tunis exile and installed in the West Bank to run a Palestinian government for the first time ever. That was the quid. After an interim period of five years, final-status negotiations were expected to bring the Palestinians an independent state that would in turn recognise Israel. That should have been the quo.

Unfortunately, Arafat pocketed all his benefits (i.e., his triumphant return to Palestine and installation as PA president) upfront. When he then reneged on his obligations to Israel, Arafat’s weaponised Nakba narrative became a self-manufactured excuse to break the Oslo agreements without suffering any penalty.

In early 1998, as Israel was preparing to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its birth, Arafat and his lieutenants were holding conversations about that upcoming event as well as another pressing issue for the Palestinians. The end of the five-year interim arrangement was approaching, which meant final-status negotiations were supposed to start.

Arafat was under conflicting pressure from two internal factions over the refugee issue. The dominant group was sometimes referred to as the “outsiders”, because they had spent the years since 1948 in exile. Salman Abu Sitta, a member of the Palestine National Council, an original refugee and one of the most active members of the outsider faction, had been urging Arafat never to give up on the right of return. In early 1998, Abu Sitta drafted a public letter to Arafat about the refugee issue that was co-signed by dozens of prominent Palestinians. It said in part:

We absolutely do not accept or recognise any outcome of negotiations which may lead to an agreement that forfeits any part of the right of return of the refugees and the uprooted to their former homes from where they were expelled in 1948, or their due compensation, and we do not accept compensation as a substitute for return.

One of the signatories was Edward Said, by now a true believer in the most extreme version of the Nakba narrative and the right of return. In an interview with Israeli journalist Ari Shavit, Said berated Arafat for even thinking he “can sign off on the termination of the conflict.”

Yet there was also a more moderate faction within the PA, including those who had never left Palestine as refugees. Some had served as local officials during the period of the Jordanian occupation of the West Bank. One of their leaders was Sari Nusseibeh, president of Al-Quds University and Arafat’s principal representative in Jerusalem. In his memoir, Once Upon a Country, Nusseibeh describes a meeting with Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas on the issue of the refugees’ right of return. Nusseibeh recounts the following exchange with Abbas:

Nusseibeh: You have to level with us. What is it you want, a state or the right of return?

Abbas: Why do you say that? What do you mean by either/or?

Nusseibeh: Because that’s what it boils down to. Either you want an independent state or a policy aimed at returning all the refugees to Israel. You can’t have it both ways.

No other Palestinian leader has acknowledged in such stark terms that when the Nakba narrative includes the right of return, it kills any chance for peace as well as for an independent Palestinian state. The return of the refugees was a deal breaker for Israel, but also for the Clinton Administration that helped broker the Oslo Accords.

Palestinian Authority leader Yasser Arafat (right) with his successor Mahmoud Abbas (left): Both have used the Nakba narrative as the key reason to reject two-state peace deals (Image: Hussein Hussein/ AAP)

A reluctant Arafat was finally dragooned by President Clinton to go to Camp David in 2000 for the final-status negotiations, but the outcome was a foregone conclusion. The PA President stormed out of the meeting after turning down a generous offer for an independent state. According to Clinton adviser Dennis Ross, in order for the Camp David summit to have succeeded, “the Palestinians had to give up their ‘right of return’ to Israel.”

After Camp David, the Clinton and Bush Administrations continued to press Arafat to reconsider his position. Instead, the PA President doubled down. In his 2004 Nakba Day speech, he made his commitment to the refugees’ right of return even more explicit:

The issue of refugees is the issue of the people and the land, the cause of the homeland and the cause of the entire national destiny, no compromise, no compromise, no settlement, but a sacred right of every Palestinian refugee to return to his homeland, Palestine.

Another round of peace negotiations took place four years later, this time directly between Israel’s Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and the PA’s President Mahmoud Abbas. They held 35 one-on-one meetings in Jerusalem over a span of seven months. At the last session on Sept. 16, 2008, Olmert offered Abbas an independent Palestinian state with its capital in east Jerusalem. He showed Abbas a proposed map of the borders of the two states that, through territorial swaps, would give the Palestinians almost 100% of the territory of the West Bank and Gaza held by the Arabs before the 1967 war. Olmert agreed to allow a token number of refugees to enter Israel on humanitarian grounds but said the agreement had to end all Palestinian claims about the right of return.

Abbas said he would consider the offer and return in a few days with his answer. But he never came back, and the negotiations abruptly ended. In an interview I conducted with Olmert a few years later, the former prime minister made it clear that the sticking point for Abbas was the right of return.

After Olmert’s proposed map became public, Abbas claimed his hands were tied because the refugees would settle for nothing less than the right to return. How, he asked plaintively, could he turn against his own people?

Left unsaid was the fact that Abbas (like Arafat before him) was responsible for spreading the Nakba lies and hatred into the refugee camps, which then sparked the militancy among the Palestinian masses who, he claimed, prevented an agreement with Olmert.

The refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza have become the permanent places of residence for more than two million Palestinians. They are administered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) established by the UN in 1949 to take care of what was expected to be a temporary humanitarian crisis. Instead, the vast network of UNRWA camps became permanent, a state within a state. After the Oslo Accords, Arafat’s PLO was able to take over the camps, albeit under the continuing legal umbrella of UNRWA.

In a video produced by the Centre for Middle East Research, children at an UNRWA summer camp can be seen singing martyrdom songs and praising suicide bombers. An UNRWA teacher promises a classroom of children as young as ten: “We will return to our villages with power and honour. With God’s help and our own strength, we will wage war. And with education and Jihad we will return.” Speaking to the camera, a teenage girl announces, “I dream that we will return to our land and with God’s help [Abbas] will achieve that goal and we will not be disappointed.”

Abbas knows that day will never come. Instead, his Government’s Nakba narrative guarantees that the Palestinian teenager will remain trapped in her refugee ghetto for decades to come. For the PA President, though, there are many benefits in perpetuating the impossible dream. It provides him with a tale of unprecedented victimhood and a seemingly just cause to champion in the international arena. It also certifies his militancy within Palestinian politics, where militancy is the coin of the realm.

To sum up, Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas revised Constantine Zurayk’s original claim that Zionism committed its crimes against the entire “Arab Nation”. But they also revived Zurayk’s big Nakba lie that “the aim of Zionist imperialism is to annihilate one people so that another may be put in its place.”

By continuing to promote this hateful narrative, the Palestinian leaders signalled, and continue to signal, that the struggle is not merely about the consequences of the June 1967 war. It also means that Israel’s struggle for independence and legitimacy is not yet over.

Sol Stern is a veteran American journalist and author. © Commentary magazine (www.commentarymagazine.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians