Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Israel looks East

Jul 1, 2022 | Daniel J. Samet

Better Asian opportunities exist than China

For ages, Jews looked east in search of Zion. Now that they have Zion, they are looking east ever still. Israeli leadership now views Asia, with its expanding markets and increasing global influence, as a crucial foreign-policy interest. While Israel has long prioritised ties with the Western world, for the past few years, the Jewish state has sought out a range of partners in the Pacific. As Israel’s then-Minister of Economy Naftali Bennett simply stated in 2015, “we’re moving to the East.”

The move is eminently defensible on its face. To treat Asia, which will account for more than 50% of global GDP by 2040, as anything other than a land of potential geopolitical and economic opportunity would be foolish. The more Israel trades with Asian countries, the more it will prosper.

What Bennett, now Israel’s Prime Minister, did not foresee was the full spectrum of challenges and hiccups that might slow Israel’s Asian pivot. The greatest and most lamentable of these is the justifiable American concern over Sino-Israeli ties. As Arthur Herman wrote in Mosaic, the problem is “whether and how [Israel’s] relationship with China could become a dependency.” Such a circumstance “would impose on Israeli national security a new kind of vulnerability, one very different from the challenges it has faced successfully in the past.” When it comes to Israel’s dalliance with China, suffice it to say that Thomas Sowell’s quip that there are no solutions – only trade-offs – is as true as ever.

Getting a better trade-off will depend on how successfully Israel woos Asian countries other than China, whose depredations abroad and human-rights violations at home ultimately make it a wanting partner. In the summer of 2021, Jerusalem took a commendable step forward on the moral front in supporting a measure at the United Nations Human Rights Council calling on China to let outside observers into Xinjiang, where it is reported that more than 1 million Uyghurs have been detained, abused, and worse. But a few months later, allegedly under pressure from the Chinese, it did not sign on to a joint statement that said much the same.

A country that embodies the sentiment “never again” should not stay silent as Beijing carries out a genocide against untold numbers of Uyghurs. Surely there are other folks in the neighbourhood with whom Israel can do business without compromising its morals.

The main contenders here are India, Japan, and South Korea. Despite their many differences, these three countries are democracies with dynamic economies, and they, too, would benefit from deeper ties with the Jewish state. What’s more, they are three of the most important players in the world’s most important region.

Casting its lot with these nations, as opposed to China, is a far better bet for Israel.

Asia was once something of an afterthought in Israel’s foreign policy. For decades, Israel focused on nearby countries. Notwithstanding its relationship with Washington, Jerusalem sought partners closer to home. Europe, with its enduring economic and political clout, figured prominently in the minds of Israeli strategists, as did nearby states such as Turkey and pre-revolutionary Iran. Complementing this Mediterranean-oriented approach was engagement with sub-Saharan African countries such as Ethiopia.

To be sure, the Jewish state did not try to make enemies outside Europe and the Middle East. It even had notable ties to countries such as Australia, Burma, and the Philippines. On the whole, however, the region just was too far afield and not consequential enough to demand the attention and resources of a small, developing country with a glut of challenges in its own neighbourhood.

Jerusalem today has become much less provincial. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Israel today maintains official ties with 160 countries and has 107 diplomatic missions. Besides the countries mentioned above, Israel today has diplomatic missions in Vietnam, New Zealand, and Singapore, to name a few.

India, according to the United Nations, will become the world’s most populous country by 2027. And it has become a cornerstone of Israel’s regional strategy. The two countries may seem like natural partners. Both are multi-ethnic democracies surrounded by majority-Muslim nations. But the current warm relations between Israel and India are a relatively recent development.

When India was itself a newly independent state, it voted against the 1947 UN Partition Plan. Nationalist hero Jawaharlal Nehru had clamoured for the partition of India into a majority-Hindu state and a majority-Muslim one but did not support the partition of Palestine. Why not? Nehru threw in his lot with the Arab bloc for reasons of realpolitik. Irrespective of its never-ending feud with Pakistan, New Delhi wanted good relations with the Muslim world. For many of these countries, being friendly to Israel was beyond the pale. Indian politicians also feared that embracing Israel might put off their Muslim compatriots at the ballot box.

Although Nehru recognised Israel in 1950, India kept the Jewish state at arm’s length throughout the Cold War. Much of this had to do with the prevailing dynamic of superpower politics. India was one of the leading voices in the Non-Aligned Movement, a group of countries formally allied with neither the United States nor the Soviet Union but that often sided with the anti-Israel Soviet sphere. Among the Non-Aligned Movement’s members were relatively new nations such as Egypt and Indonesia that viewed the world as one anti-colonial struggle in which Israel was another imperialistic oppressor. India hewed to this line.

The end of the Cold War, however, brought an end to that arrangement. Not only did the two countries open mutual embassies in 1992, but official high-level contacts between the two nations began to increase. Israeli President Ezer Weizman visited India in 1997, while Prime Minister Ariel Sharon followed suit in 2003. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi notably met Binyamin Netanyahu in New York City in 2014 before coming to Israel three years later. Modi, who called his trip “ground-breaking,” became the first Indian prime minister to visit the Jewish state. Netanyahu returned the favour the following year. Both heads of government acted like pals on Twitter, where Modi called Netanyahu his “dear friend,” and Netanyahu similarly referred to his “great friend” Modi. As prime minister, Bennett has kept up the chumminess, letting Modi know that he was “the most popular person in Israel” during the UN climate summit in November 2021. There is surely the will on both sides to keep expanding ties.

One way to do so lies in the security realm. Israel has been as keen to sell India weapons as India has been to buy them. From 2016 to 2020, when India accounted for 9.5% of arms imports worldwide, Israel was the country’s third-largest weapons supplier. Israel’s defence industry has been hard at work providing India with reconnaissance equipment, small arms, and munitions, as well as missile-defence systems. Further consolidation of the defence relationship came at a joint working group meeting in Tel Aviv in October 2021, where the two countries agreed to design a ten-year road map to strengthen defence cooperation.

Both Israel and India are democracies threatened by radical Islamic terrorism. Beyond weapons sales, intelligence-sharing has proliferated among the two countries in recent years. Although it would be premature to call their defence cooperation an alliance, New Delhi and Jerusalem have made significant strides in this area.

The same is true of economic relations. Bilateral trade between the two nations reached nearly US$3.4 billion in 2020, the most recent year for which such data are available. India has become Israel’s third largest trading partner in Asia and its seventh largest worldwide. Gems and chemicals make up the lion’s share of bilateral trade, augmented by a surge in the exchange of consumer goods such as high-tech wares and communications systems.

At a joint appearance in Israel last year, Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid and Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar disclosed that their two countries would undertake free-trade talks in hopes of concluding a pact by mid-2022. During his remarks, Lapid hailed India as “a very important ally.”

This is not to say that Israel-India relations are without challenges. For one, doing business in India is not easy. Even given the size of its economy, would-be investors in India may be deterred by the country’s seemingly endless red tape. To alleviate these concerns, Modi’s Government has pared back the regulatory state and is actively courting Israeli investment.

One worrying obstacle to deeper cooperation is India’s connection to Iran. The two countries have often had amicable relations over the past few decades, and since Ebrahim Raisi became Iran’s President in 2021, New Delhi has made a concerted effort to get into his good graces.

But don’t count on either the Iran factor or the Indian bureaucracy slowing down Israel-India cooperation. The benefits still outweigh the drawbacks: Each side can delicately pursue its respective interests without imperilling the other’s. If Netanyahu’s line that India and Israel are “a marriage made in heaven” proves true, then New Delhi and Jerusalem will have come far since the founding of the Jewish state.

But what should give promoters of the relationship the most pause is Modi himself. Under his leadership, India is less democratic than it was just a few years ago. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in addition to championing legitimate Hindu nationalist concerns, has derided Muslims as a threat to Indian unity and passed discriminatory laws against them. Elsewhere, Modi has been gung-ho to crack down on operations by NGOs and the free press. Freedom House, whose yearly Freedom in the World Report measures democratic development, has downgraded India from “Free” to “Partly Free”. Shouldn’t those who protest Israel’s dealings with China also protest its dealings with India?

The questions are worth wrestling with. But let’s dispel any sort of moral equivalence between totalitarian China and democratic India. No one in the former has the right to vote. The latter has universal suffrage. China represses ethnic and religious minorities on a massive scale. India is home to more than 2,000 ethnic groups that, despite democratic backsliding under the BJP, enjoy a degree of pluralism unthinkable in China. Doing business with New Delhi is not the same as doing business with Beijing.

Japan is a different story altogether. As regards Israel-Japan ties, the moral questions are scarcely there. Now far removed from its imperial past, the Land of the Rising Sun is today a vibrant democracy and an upstanding neighbour. Japan does not prey upon countries nearby. Nor does it curb the rights of its own citizens.

Relations between Israel and Japan date back to 1952, shortly after the Allies handed back sovereignty to Tokyo and the Jewish state won its independence. Unlike non-aligned India, Japan became a treaty ally of the United States following World War II and pursued a foreign policy that was largely congruous with Washington’s – except when it came to Israel.

Tokyo kept its distance from Israel for decades. A much-reduced strategic player on the world stage, Japan saw the Middle East through the lens of energy, not geopolitics. By the 1970s, its economy (then the second-largest in the world) had grown exceptionally reliant on imported oil. Israel could not offer Japan anything in that regard, but other countries in the region could. Once Arab states in OPEC imposed an oil embargo against the United States and its allies following the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Tokyo sided with the Arab world in public pronouncements. It stopped short of boycotting Israel, but commercial ties suffered nonetheless.

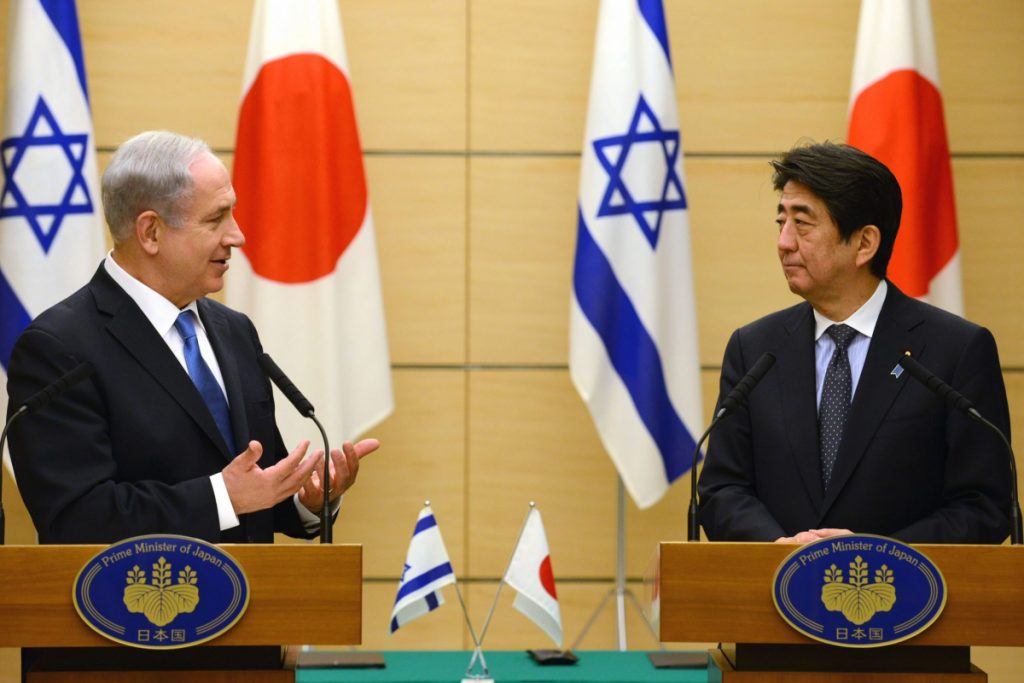

Then Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu with his Japanese counterpart, Shinzo Abe, during a breakthrough visit to Japan in 2014 (Image: Isranet)

It was only in the 21st century that relations thawed. The changing strategic outlook in the Middle East and elsewhere made Tokyo see the utility in cosying up to Jerusalem. No longer did dependence on Arab oil mean shunning the Israelis. Tokyo reckoned that Arab petrostates would no longer go to the mat for the Palestinians in defiance of Israel, whose growing economic power the Japanese wanted to engage. Japan shed its qualms about bettering relations.

Growing person-to-person contacts reflect this new environment. In 2014, Netanyahu made an official visit to Japan during which he met with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Emperor Akihito. The following year, Abe made a visit to Israel – the first by a Japanese prime minister since 2006.

Economic ties are front and centre. Tokyo and Jerusalem have floated the idea of a free-trade agreement for years, though talks have yet to yield anything concrete. Bilateral trade is still relatively modest. Investment, however, has already seen significant progress. In 2020, Japanese companies invested a record US$1.1 billion in Israel, up 20% from 2019, and 11.1% of foreign investment in the Israeli high-tech sector comes from Japan.

Commercial interests explain why both countries want to do business with each other. Japan is home to a population of more than 120 million, it has the world’s third-largest economy, and it has leading industries in automobiles, semiconductors, and electronic goods, among others. In some ways, Israel is a scaled-down Japan: Both countries are democratic and have high-income market economies with an industrious, highly educated workforce. A nation as innovative as Japan would seem a natural friend for the “start-up nation”.

Defence ties between the two are currently negligible. That could soon change. In 2019, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding on defence cooperation at the Japanese Ministry of Defence. “We have brought Israel-Japan relations to an all-time high,” Netanyahu said after the ceremony.

That remark must have had more to do with relations in general, not defence relations in particular. Japan’s overriding security challenges come down to China. Israel’s do not. As far as terrorism is concerned, Japan is in much less danger than Israel and plays a much smaller role in the Middle East’s security landscape. Absent a convergence of strategic interests, Israel and Japan may believe that there’s little reason to cooperate significantly on defence.

This might be a missed opportunity. Israel and Japan have a shared interest in blunting North Korea’s nuclear technology. North Korea poses a clear and present danger to Japan, which, after South Korea, is the country most threatened by Pyongyang’s aggression. It also poses a threat to Israel. North Korea has been an active patron of Iran’s and Syria’s nuclear-weapons programs. Israel may not be in the crosshairs of a North Korean nuclear strike, but the possibility of Kim Jong Un and company helping hostile states or non-state actors get the bomb is a serious concern of Israeli defence planners.

Israel might be reluctant to sell advanced weaponry to Japan, however, for fear of antagonising China and jeopardising cooperation with that country. But intelligence-sharing is another matter. A 2018 cybersecurity-cooperation pact signed by Israel and Japan lays the groundwork for exchanging much more sensitive information. If and when threats evolve, this architecture could expand to cover issues outside the Korean Peninsula.

There is, also, another, more familiar problem. Like India, Japan is close to Iran. Tokyo has historically relied on Teheran to supply much of the oil powering its economy. Iran has pressed Japan to defy US sanctions on Iranian oil exports, including during a visit by Abe in 2019. Before the Trump Administration reimposed those sanctions in 2018, Japanese imports of Iranian oil had bounced back, though far below their pre-sanctions high. Israeli national-security officials will be justifiably cautious about sharing intelligence with Japan. But Iran cannot arrest the broader growth of Israel-Japan relations.

South Korea also has a troubled history with Israel. In 1962, Israel and South Korea established official diplomatic relations. This came after years of informal ones, when the Jewish state supported South Korea and US-allied forces during the Korean War. This was the start of significant relations between the two countries. But like Japan, South Korea voiced support for the Arab states throughout the 1970s. Under Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, ostensible budgetary limitations led Israel to close its South Korean embassy in 1978, which proved a geopolitical misstep. Economic ties ground to a standstill in the wake of the decision, and the embassy would not reopen for another 14 years.

Then Israeli President Reuven Rivlin visiting South Korea – a key partner for Israel in east Asia – in 2019 (Image: Isranet)

After a long stasis, ties have become markedly better. In May 2021, Seoul and Jerusalem signed a free-trade agreement, making South Korea the first Asian country to do so with the Jewish state. The agreement should increase bilateral trade, which totalled roughly US$2.4 billion in 2020. It will pay dividends in terms of the South Korea-Israel relationship while showing other countries that Israel can strike a deal with one of the world’s richest countries.

Economics is not the only thing drawing Israel and South Korea together. South Korea is a stable democracy in an increasingly unstable corner of the globe. Eager to defend itself against the regime in Pyongyang, Seoul has purchased Israeli weapons in the past few years. Notable sales include the Oren Yarok radar system and the Harpy UAVs, the latter being the same drones Israel tried to sell to China before US lobbying killed the deal. Prior to purchasing trainer aircraft from Italy in 2012, Israel considered opting for South Korean T-50s instead.

Efforts at joint weapons development have also gotten off the ground. An agreement between Israeli and South Korean aerospace firms signed in October 2021 paves the way for cooperation on drone technology. Relatedly, following proposals to acquire the Iron Dome from Israel, South Korea recently moved to build a system modelled on it.

A good foreign policy looks to the future, not just the present and past. Israel’s handling of its relationships with India, Japan, and South Korea may be a harbinger of even more breakthroughs in the region. Jerusalem has pushed to normalise ties with Indonesia and Malaysia, albeit to no avail quite yet. A bigger Israeli presence in Asia might give Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur all the more reason to start anew with Jerusalem.

“East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” reads a famous Rudyard Kipling poem. What’s happening in the Middle East and the Far East suggests otherwise.

Daniel J. Samet is a Ph.D. student in History at the University of Texas at Austin and a Krauthammer Fellow with the Tikvah Fund. © Commentary Magazine (www.commentarymagazine.com) reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Asia, India, Israel, Japan, South Korea