Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Grandstanding Against Peace

Oct 29, 2015 | Glen Falkenstein

The sporting boycott of Israel

Glen Falkenstein

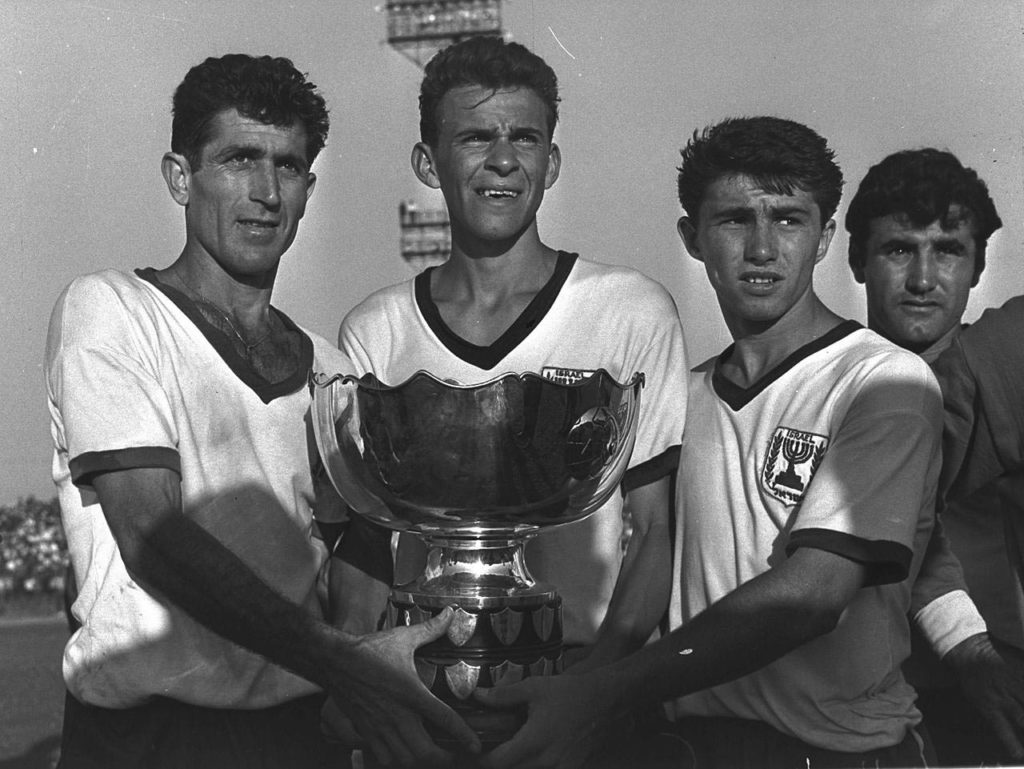

There was something missing from the Asian Cup this year when it kicked off in Australia. Not only was there the absurdity that an Israeli team was not present, despite being in geographically the same area as the Palestinian territories – which did send a team to the competition – but any mention of Israel’s participation and previous success in the Cup was absent from the official competition video showcasing the tournament’s history.

These are just the latest examples of the extent to which Israel has been subject to a widespread boycott of its sporting teams and players over decades, ranging from intimidation and aggression directed at individual players or groups, to a refusal to either associate or compete with Israel in tournaments and official competitions.

This is not just a result of the comparatively recent Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel, though BDS groups have certainly been happy to join in. Instead, like so much of what BDS groups do, it originates in the Arab Boycott of Israel, which itself has been in existence in various forms since the 1920s.

While having limited, if any, financial or tangible impact on Israel, this long-standing element of the Arab Boycott has had a recognisable impact on “soft diplomacy” – it furthers the efforts of some states and anti-Israel activists to delegitimise Israel. Perhaps the saddest impact of the sporting boycott of Israel is the extent to which it undermines opportunities for cross-national and cross-community cooperation and understanding through sport – especially as part of efforts to bridge the Israeli-Palestinian divide.

The Soccer Boycott

Israel was not in Australia for the Asian Cup because, while it historically was a part of the Asian Football Federation, a number of Arab countries refused to play Israel and in 1974 a Kuwaiti motion to expel Israel from the AFC was adopted. Today, Israel plays in the European confederation and is still barred from competing in the Asian Cup. No other country has been excluded for political reasons – even North Korea is allowed to compete. So are players representing the Palestinian territories, which qualified for this year’s tournament amid significant publicity. At the least, their participation demonstrates that Israel is geographically as much a part of Asia as other competing nations.

At the competition in Australia earlier this year, organisers of the Cup indicated they were “baffled” by the omission of any mention of Israel – a former host and winner of the cup in 1964 – in the official video history of the Cup which managed to showcase all 14 other previous winners. An employee of FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association, soccer’s world governing body) commented in response to the incident, “it’s upsetting but I’m not surprised.”

FIFA itself, along with UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) has, come under huge pressure in recent years from Palestinian groups, pro-Palestinian NGOs and allied nations, to ban Israel completely from participating in international tournaments.

In the year leading up to Operation Cast Lead, more than 60 European soccer players, including some from Chelsea and Arsenal and lead by ex-Tottenham Hotspur player Freddie Kanoute signed a statement protesting Israel’s hosting of the UEFA Under-21 championship. The sponsors cited Israel’s actions in relation to Gaza and urged the UEFA to re-think its decision, claiming that permitting Israel to host would be “seen as a reward for actions that are contrary to sporting values.”

Following the conflict, an additional statement was sent to the head of the UEFA by 75 Palestinian teams and NGOs discouraging the Union from pursuing greater association with Israel, stating: “holding the UEFA 2020 games in Jerusalem would be tantamount to ‘rewarding’ Israel for its massacre of more than 2,100 Palestinians.”

Central to the effort to suspend Israel from FIFA has been the Palestinian Football Association (PFA) and its President Jibril Rajoub, former head of the West Bank Preventative Security Forces, who was convicted of throwing a grenade at an Israeli Army truck in 1970. He has primarily tried to justify the demand for expulsion by citing Israel’s restriction of players’ movements between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip – restrictions applied not exclusively to soccer players, which Israel says are necessary for security reasons.

Activists have also focused on two Palestinian soccer players who were arrested – in each case for terrorism offences, not for anything to do with soccer. Thus Mahmoud Sarsak, a player arrested in 2009, admitted to being a member of Palestinian Islamic Jihad, while Omar Abu Rwayyis was arrested in 2012 for helping transport Kalashnikovs that were used to fire on IDF vehicles in a Hamas-sponsored attack.

Further, in 2014 Rajoub promoted the case of two teenage Palestinian soccer players when it was claimed that they had been shot while walking back from a training session. Elements of the reports surrounding the incident turned out to be false, with both apprehended while throwing bombs at security forces.

Rajoub went so far as to pull out a red card before the television cameras at the 65th Congress of FIFA in May and wave it at the podium in opposition to what he called “racism” and “humiliation.”

A documentary aired on the ABC’s “Foreign Correspondent” focused on the Palestinian team’s participation in the Asian Cup, which made it very clear that a tactical decision had been made to employ soccer as a key tool in the conflict with Israel. Rajoub said that the Palestinian soccer team is “a tool… to achieve my people’s… aspirations,” comparing it to “using machine guns and grenades.” Team official Amr Hannoun also stated in the documentary that “we’re just looking to football as a political message.”

The ensuing FIFA drama escalated to the point where the organisation’s leaders travelled to the Middle East [amid an already highly-publicised and wholly separate corruption scandal within FIFA] to meet with both Prime Minister Netanyahu and President Abbas. Arab delegations to the organisation even went to the extent of walking out of a meeting when Israel’s Football Association President attempted to address them.

Ultimately, the PFA dropped its call to suspend Israel from FIFA during a FIFA Congress when it was overruled by the Association’s President, Sepp Blatter, who clarified that the Congress “cannot interfere into political territories” and noted the obvious – the Israeli Football Association, which Rajoub demanded be suspended, is a private body which has no control over the security policy of the Israeli Defence Forces. Rajoub characterised the action as the PFA having suspended its campaign, but not withdrawing the application, stating “it does not mean that I give up the resistance”.

A compromise was reached where FIFA would call for the creation of a committee to investigate the freedom of movement of Palestinian soccer players. The decision to halt the campaign was heavily criticised by Palestinian civil society groups and labelled by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation as a supposed violation of national principles.

The Wider Sports Boycott

As it happens, tensions have not been limited to the soccer field and extend to any number of competitive forums. In many instances, countries have attempted to exclude Israeli players from international competitions or otherwise refuse to allow their players to compete against them. In such circumstances, Israeli players have been unable to compete, or have been forced to do so covertly.

For example, members of the 2013 Israeli Delegation to the World Youth Chess Championships in Dubai, aged 10-18, were forced to compete anonymously. The hosts agreed to receive the delegation provided there was no insignia identifying them as Israeli, while all mentions of Israel competing were removed from the website.

More recently, World Jewish Congress CEO Robert Singer slammed Indonesian authorities for denying a visa to an Israeli badminton player to compete in the World Badminton Championships in Jakarta, stating, “Let’s be clear about this: Here we have yet another blatant attempt to mix politics and sports, and to exclude Israeli athletes from international competitions.” The refusal caused controversy internationally and eventually resulted in the player being granted his visa.

These controversies are not limited to sporting tournaments and can also affect other international competitions. Earlier this year, the Israeli entry for the Miss Universe competition posted a selfie on Instagram with three other contestants, including Miss Lebanon Saly Greige. Greige was subsequently criticised in the Lebanese media for the selfie and what was seen as “fraternising” with the representative of an enemy state. A social media backlash demanded that Greige’s title be taken away from her – following the precedent of what actually happened to the 1993 Miss Lebanon after she was photographed with Miss Israel.

Greige responded by insisting that she had been ambushed in the photo, stating, “From the first day I arrived at the Miss Universe pageant I was very careful not to take any pictures with Miss Israel, who tried repeatedly to take pictures with me… While I was preparing with Miss Slovenia and Miss Japan to get our photograph taken, Miss Israel jumped in and took a selfie with her phone and posted it on social media.”

Greige’s agent even claimed that Miss Lebanon had to “run away” several times because she was being chased by Miss Israel for a photograph.

Miss Israel, Doron Matalon, commented: “Too bad you cannot put the hostility out of the game… I hope for change, and I hope for peace between us; even just for three weeks, even just between me and her,” adding, “it doesn’t surprise me, but it still makes me sad.”

Ultimately, Miss Lebanon did not lose her title, with the Lebanese Tourism Minister stating: “According to the information we obtained, Miss Lebanon did not have bad intentions that necessitates her being stripped of her title or punishment.”

This is one of the last things anyone would expect from a competition in which the contestants often profess their desire for world peace. I saw at least one newsreader awkwardly read the news that day, stating: “There is political fall-out after a selfie was taken at the Miss Universe pageant.”

The unique characteristics of the sporting boycott

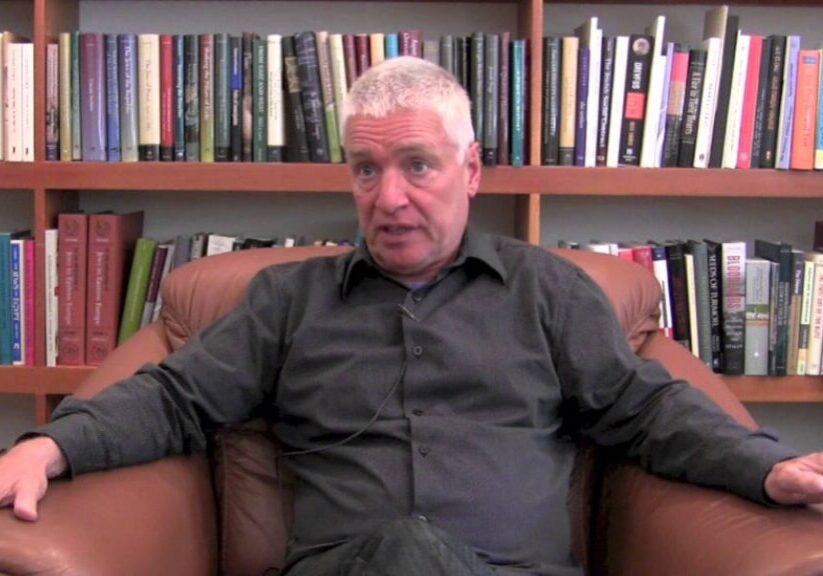

Manfred Gerstenfeld, an author specialising in researching the international boycott campaign, sat down with AIJAC to discuss where the sports boycott fits into the goals of the overall boycott campaign against Israel:

“What these people want is to turn Israel into a pariah state so you boycott everything from Israel. The boycott idea stems from the Durban NGO ‘antiracism’ conference in 2001. The BDS promoters took it from there and thought it would take 5 years to be successful but it has taken much longer to make any impact. The tremendous shortcoming of successive Israeli governments is that they have neglected this sizable attack.

“Even if the boycott fails, its promoters are interested in the publicity. It affects the image of Israel and that’s what they want to do; the successive Israeli governments have for many years not understood anything about it.”

Gerstenfeld, the former chairman of the Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs, classifies sporting boycotts as part of the “non-economic” side of the boycott:

“An example of a non-economic boycott is banning the participation of sportsmen from a certain country in international competitions. Such boycotts have been applied against countries such as South Africa and Taiwan. Israel has been excluded from various Asian competitions.”

He explained the overall goal of such efforts is to embarrass and marginalise:

“The non-economic boycott hardly affects Israel financially in any way but it may be an embarrassment for some individuals. If you are an academic in a field which is being boycotted then you are not invited to conferences and your work and so on is affected. In a sports boycott for instance, Israeli athletes cannot participate in a competition; it affects them… The academic, cultural and sports boycotts are radically different from the economic boycott.

“Israel cannot participate in a number of Asian sports competitions including soccer… The harassment of individual players in tournaments is occasionally a problem.

“They (boycott supporters) want Israel to be excluded from the cultural scene. If you are not allowed to play international soccer you are excluded from the sports scene, if academics don’t invite you then you are excluded from the academic scene.”

How sport can contribute to peace

Advocates of sports boycotts often see any contact between Israelis and Palestinians on the field as forbidden “normalisation” with Israel. Jibril Rajoub famously said in 2014, “Any activity of normalisation in sports with the Zionist enemy is a crime against humanity.”

Yet despite the hardline position represented by Rajoub and many others in the Palestinian leadership, clearly contrary to hopes for future peaceful coexistence, numerous programs demonstrate the value of continued participation and engagement between Israelis, Palestinians and others through sport. Sporting and competitive forums represent an important avenue for building meaningful connections, reconciliation and countering the harmful effects of sporting and other boycotts.

A highly publicised example of co-operation remains the joint Israeli-Palestinian Australian-Rules-football team comprised of 26 players from both national backgrounds, who came together in 2008 for an international tournament. The team, which had widespread support among Jewish and Muslim communities, was the subject of a documentary film which won numerous awards. A 16-year-old Palestinian boy explained on the Al-Quds Association website what he learned as part of the initiative:

“Peace is possible in the world we live in today, sport unites us; it doesn’t separate us. Our project shows the whole world that Palestinians and Israelis live together, that they can be friends and allies, despite what other people say.”

The Al-Quds Association has also partnered with the Peres Centre for Peace in order to build a Peace Sport Schools program which is now the longest-running coexistence sports project in the Middle East, involving thousands of children both Israeli and Palestinian annually. According to the organisation’s website, “The program fosters values of peace and coexistence amongst young Palestinians and Israelis by changing attitudes toward the ‘other’ and diffusing [sic]stereotypes. In locations across Israel, in both Jewish and Arab communities, and in Palestinian communities across the West Bank, the Peres Center and Palestinian partners establish Sport Schools, where children participate in bi-weekly after-school sports training, peace education activities and inter-language learning.”

In May 2014, Australian ultramarathon runner Pat Farmer ran through Lebanon, Jordan, the West Bank and Israel as part of a “Middle East Peace Run” concluding in Jerusalem. While not without controversy, the Peace Run was generally regarded as a success. Farmer commented:

“If this is driven from a grassroots level, by the people on the ground, and just in support of it by simply running with me, then I think that’s a pretty powerful petition to take to the various leaders to be able to say, ‘look, this is what we want, we want peace, so just get on with it.'”

Competing for peace

The reality is that beyond simply counter or “reactive” measures to boycotts, active “sports diplomacy” and bridge-building has been a sought-after strategy in many forums. Andrew Hunter, former senior advisor on international engagement to South Australian Premier Jay Weatherill, noted the ability of ‘sports diplomacy’ to break down barriers, commenting:

“Opportunities for breakthrough diplomacy are rare but sport can play other roles in the national interest. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop noted in the Commonwealth’s strategy that ‘sports diplomacy is an increasingly important aspect of diplomatic practice and a growing part of the global sports industry.’

“Sport is a vehicle for intercultural exchange which can bring mutual benefit through a shared passion and a common, unspoken language.”

Competitions have historically served as an important forum for reconciliation and diplomatic exchange, not least in 1971 when a table-tennis team became the first US delegation to set foot in China in 22 years.

Cricket fans might remember the 2011 World Cup semi-final between India and Pakistan, two countries with historic and ongoing tension. The night of the match, I attended a function hosted by one of the semi-finalist countries at their Embassy in Washington. Speaking to an Embassy official, I learnt how over decades, and even today, senior officials from both countries could attend such a match and discuss issues through informal contact – thus strengthening ties and reducing tensions.

The boycott and “anti-normalisation” campaigns have sought to cut off all cultural ties or collaboration between Israelis and Palestinians in the sports world, yet these ties will be crucial if both groups are going to live peacefully together in a future two-state solution and continue co-operating on and off the field.

Refusing to play ball with Israelis, or even exchange simple courtesies, should be beyond the pale, whatever you think of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Much was made of Palestine’s significant participation in the Asian Cup, a competition which Israel was not allowed to enter. It is entirely possible that had Israel been eligible for the Cup, both sides could have set an example for others to follow and helped foster grassroots efforts for peace.

This article is featured in this month’s Australia/Israel Review, which can be downloaded as a free App: see here for more details.

Tags: Anti-Zionism, Indonesia