Australia/Israel Review

Deconstruction Zone: 75 years of self-inflicted injury

Dec 15, 2022 | Mark Regev

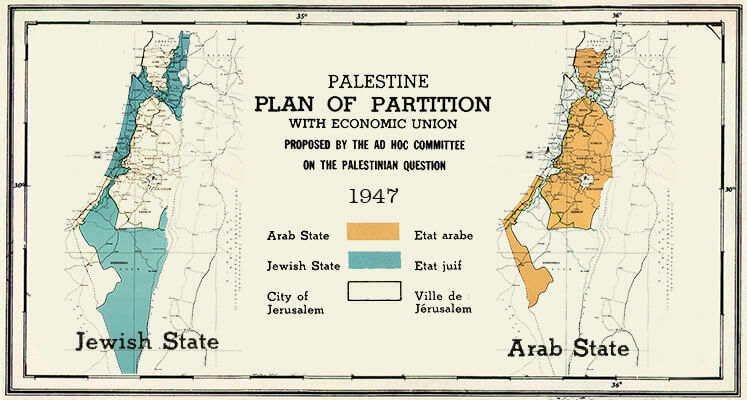

It is well known that on November 29, 1947, the Palestinian Arabs rejected the UN partition proposal that awarded them an independent sovereign state in the territory of British Mandatory Palestine. Less understood is that they not only harboured a deep ideological hostility to the concept of partition, but also opposed all other possible alternative compromises with the Jews.

For Zionists, the partition plan was undoubtedly flawed: the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) divided the homeland; allotted the Jews territory separated into three areas (two of them very small and the third largely desert); and internationalised Jerusalem, leaving the ancient capital outside the borders of the proposed Jewish state.

Nonetheless, the Jews celebrated the General Assembly’s support for partition. For them, the UNSCOP plan’s multiple drawbacks were mitigated by one overriding factor: the organised international community had endorsed the principle of Jewish statehood. Everything else was secondary.

Popular enthusiasm for the resolution can be seen in black and white footage shot contemporaneously: The Jews of Mandatory Palestine glued to their radios, listening to the live broadcast from Lake Success where the UN was meeting; marking down each UN member’s vote in the “yes”, “no”, or “abstain” columns – and when the two-thirds majority was achieved, erupting in spontaneous jubilation, literally dancing in the streets.

While Jews in their thousands rejoiced in the UN vote, an important minority refused to be caught up in the enthusiasm. Underground commanders, the Irgun’s Menachem Begin and Lehi’s Yitzhak Shamir – both future Likud prime ministers – staunchly opposed partition.

So, too, did important elements in the labour movement: Yitzhak Tabenkin’s United Kibbutz and Meir Ya’ari’s Hashomer Hatzair – the former committed to the land of Israel, the latter championing a Marxist bi-nationalism.

Amazingly, the partition vote saw the two Cold War arch-rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, line up on the same side of the debate.

In contrast to the narrative portraying Israel as a colonialist implant, Jewish statehood received backing not merely from Western countries like the US, France, Australia, Canada and the Netherlands, but also from anti-imperialist Communist Bloc countries like Czechoslovakia and Poland, and the Soviet Union itself.

The Soviet UN delegate, Andrei Gromyko, in support of partition, declared: “The fact that no Western European state has been able to ensure the defence of the elementary rights of the Jewish people and to safeguard it against the violence of the fascist executioners explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own state.”

Concurrently, Great Britain, the Middle East’s hegemonic colonial power, opposed Jewish independence and later provided military support to the Arab countries in their attack upon the nascent State of Israel.

Unlike the Jews, who heatedly debated the pros and cons of partition, the Palestinian Arab leadership did not entertain public doubts. Its united opposition to the UNSCOP plan was consistent with a longstanding hardline approach. A decade before the 1947 vote, the Palestinians turned down the British government’s Peel Commission partition plan that awarded the Arab side some 75% of the territory.

It was not just a Jewish state, regardless of its size and borders, that was abhorrent to the Palestinians. They rejected both the UNSCOP majority report favouring partition, backed by eight of the committee’s 11 members, as well as its minority proposal, supported by three members, which called for a federal unitary Palestine in which the Jews would enjoy an autonomous status. Apparently, any arrangement that protected the Jews’ national rights was deemed repugnant.

As threatened by Arab UN representatives, the passing of UNSCOP’s partition proposal led to an immediate escalation of Palestinian violence against the Jews. And in May 1948, when the British Mandate ended and the State of Israel was established, the surrounding Arab countries invaded in support of their Palestinian brethren.

THE BOTTOM LINE: Upon suffering diplomatic defeat in the General Assembly, the Arab world chose to overturn the UN’s determination through the force of arms. The ensuing bloodshed and displacement stemmed directly from that decision.

This upcoming May, the Palestinians will not be joining the Israelis in celebrating the 75-year existence of the Jewish state. Instead, they will mourn their Nakba (“catastrophe”). But perhaps they should recall, at a historic inflection point – as the Union Jack was lowered and the colonial power departed – when the opportunity for sovereignty was within reach, which side embraced partition, and which side rejected it.

Ultimately, had the Palestinian position been more pragmatic and moderate, they too could have been celebrating a diamond jubilee Independence Day alongside Israel.

Ambassador Mark Regev, formerly an adviser to the Israeli prime minister, is chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy at Reichman University. © Jerusalem Post (www.jpost.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians