Australia/Israel Review

Could Saudi-Israeli normalisation lead Jakarta to follow suit?

Aug 30, 2023 | Giora Eliraz

Against the backdrop of increasing media reports regarding a potential normalisation agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia, negotiated and underwritten by the US, questions about a possible Indonesian shift in policy towards Israel are again coming to the surface.

Discussion of Saudi-Israel normalisation inevitably recalls the reports from a few years ago when the Trump Administration pursued normalised relations between Israel and various Arab nations, culminating in the Abraham Accords in 2020. There were expectations at that juncture that the US might persuade Indonesia to reconsider its stance and agree to normalise relations with Israel. However, Jakarta soon denied such speculation, asserting it would not normalise relations until a comprehensive peace agreement between the Palestinians and Israel was achieved.

The Palestinian cause resonates powerfully within the Muslim majority in Indonesia – based on emotional chords of pan-Islamic solidarity. The Palestinian struggle is largely perceived as a cause that engages all Muslims. So, when it comes to policy towards Israel, domestic opinion considerations have a heavy influence on national decision-making, lest policy change trigger a major public backlash, especially from Islamic groups.

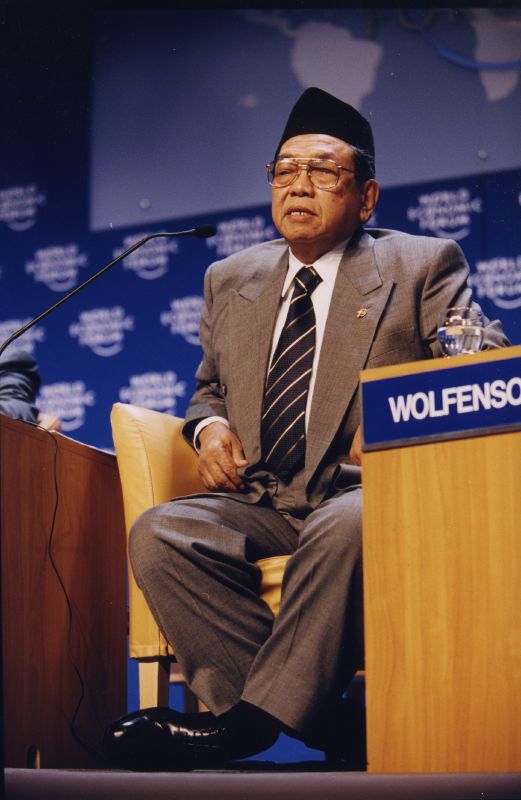

The domestic forces that blocked the plans of former Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid (above) for closer ties with Israel are still powerful in Indonesia (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Such risks act as a constraining factor on available policy choices. This dynamic was clearly evident during the presidency of Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001). His plan to move towards official diplomatic relations with Israel by first establishing direct trade ties met with robust opposition, and his government was ultimately forced to abandon it.

Normalisation of relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia might – or might not – be a game changer.

Saudi Arabia, as custodian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, is seen as the hub of the Sunni Muslim world and the centre of Islamic religious inspiration. Of course, there are many high hurdles that must be cleared before normalisation can occur between Riyadh and Jerusalem. But assuming the Biden Administration manages to negotiate a normalisation deal, this could significantly reduce the weight of domestic constraints on policy change in Jakarta towards Israel.

Would this be enough to make a breakthrough possible? Not necessarily. Indonesia’s strong commitment to the Palestinian cause should actually be seen first, historically speaking, in the context of its long-standing national anti-colonialist stance and ethos, traceable back to both the War of Independence against the Dutch (1945-1949) and Indonesia’s role in the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1950s.

The national commitment to the Palestinian cause and distance towards Israel is often publicly claimed to be an outcome of the first clause of the preamble of Indonesia’s Constitution of 1945: “With independence being the right of every nation, colonialism must be eliminated from the face of the earth as it is contrary to the dictates of human nature and justice.” Such binding national policy guidelines built into the Constitution, and formulated by the forefathers of the Indonesian state, have been absorbed into national public discourse, and sustain anti-Israel antagonism. So, it is these constitutional national arguments about “Colonialism”, rather than Islamic arguments, that appear as the main leitmotif in Indonesian debates about the question of establishing diplomatic relations with Israel.

Hence, even if the risk of strong domestic opposition motivated by pan-Islamic sentiments would significantly decrease in Indonesia following normalisation of relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel, there would still be a national ideological rubicon any Indonesian government would need to cross before Jakarta would or could follow Riyadh’s example.

A policy change might remain anathema as long as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not resolved and an independent Palestinian state has not been established – or at least as long as there is no substantial movement toward such a resolution.

The two striking cases early this year – in which the stubborn opposition of top Indonesian political leaders to the participation of Israel athletes in international sporting events cost the country the rights to host these events – offered a fresh reminder of how high a hill to climb official Indonesian relations with Jerusalem still remains.

FIFA revoked Indonesia’s hosting rights for the Under-20 soccer World Cup, while Indonesia announced its withdrawal from hosting the Association of National Olympic Committees World Beach Games. No specific official explanations were given in either case, but the political context was quite clear. Leading politicians from the ruling party PDI-P led the opposition to Israeli participation in both events, emphasising a firm commitment to the Palestinian cause and rejecting ideological compromise by citing the constitutional clause condemning colonialism. Observers also suggest that these moves opposing Israeli participation in sporting tournaments likely indicated a calculation ahead of the 2024 general elections, that such a stance would lead to wider support for the party among Muslim voters.

However, Indonesian soccer fans directed their frustration towards these politicians for politicising sports and costing the country a unique opportunity. Outgoing President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), despite pursuing his political career through the PDI-P, tried unsuccessfully to avoid losing the rights to host the FIFA tournament and publicly argued that sports and politics should be kept separate.

Nonetheless, Jokowi did not succeed in keeping the Under-20 World Cup hosting rights, and the majority view in Indonesia now seems to be that political leaders went too far in unyieldingly extending ideological maxims relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict into international sporting matters.

Indeed, there is some historical irony to Jakarta’s apparent rigidity in this case – Indonesia actually has an impressive record of supporting conflict resolution and navigating pragmatically and adeptly the turbulent waters of the international arena. However, when it comes to its policy towards Israel, Indonesia’s overall pragmatic approach appears to disappear. Even Qatar, a nation that not only has no diplomatic relations with Israel but openly supports Hamas, dedicated to Israel’s destruction, clearly understood that international sports is not the place to take a stand on anti-Israel principle. In 2019, Doha enabled Israeli participation in the World Beach Games and, in 2022, it permitted Israeli football fans to attend FIFA World Cup games there, even though the Israeli team did not qualify.

Indeed, even Indonesia has shown more pragmatism in the past. As recently as last February, shortly before the football controversy gained momentum, an Israeli athlete, track cyclist Michael Yaakovlev, stood on the podium in Indonesia proudly wearing an Israeli national uniform with his country’s flag flying next to his name, after he secured third place in a heat of the Jakarta Cup of Nations. Indonesians could even learn about this event through reports in their own language.

Israel has courted Indonesia since its earliest days, hoping back in the fifties that Jakarta might follow the example of another significant non-Arab Muslim-majority country, Turkey, which became the first Muslim-majority country to officially recognise Israel in 1949. It soon became clear that Jakarta viewed things very differently to Ankara.

Since then, not much has changed; Indonesia consistently denies engaging in any official interactions with Israel (despite the considerable covert trade that exists, mostly via Singapore).

So could the normalisation of relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia finally lead to a change? It would weaken the pan-Islamic argument and domestic political constraints against diplomatic relations with Israel – but not the argument based on “anti-colonialist” tradition. The outcome of Indonesia’s self-destructive sports boycotts from earlier this year could also have some effect. But it is far from clear this would be enough to get the establishment of full Israel-Indonesia diplomatic ties over the line.

Dr Giora Eliraz is an Associate Fellow at the Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a Research Fellow at both the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at the Reichman University, Herzliya and the Forum for Regional Thinking (FORTH).

Tags: Indonesia, Israel, Saudi Arabia