Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Centre Stage

Mar 27, 2019 | Amotz Asa-El

Asked by a reporter during one of his election speeches whether the crowd facing him was right or left, Lt-Gen. (res.) Benny Gantz replied: “It’s Israel; left, right – doesn’t matter.”

True or not about that particular audience, political centrism indeed is the quest of Gantz’s Blue and White party, the new political grouping that has barged into Israel’s political scene in an effort to unseat Benjamin Netanyahu, and bring his era to its end.

It’s nothing new. The centrist ticket has been a feature of Israeli politics since its inception, and indeed was there before Israel’s birth. In fact, Blue and White seems reminiscent of multiple centrist predecessors in terms of its target audience, range of varied candidates, and eclectic ideas.

Left and right political views in Israel are defined first and foremost by attitudes toward the conflict with the Palestinians, and only secondarily by the social and economic issues that define political identities elsewhere.

On the conflict, Blue and White has chosen a centre-right stance, avoiding mention of the two-state solution, saying only it will call for a conference with Arab governments in order to jointly seek “separation” between Israel and the Palestinians.

To further portray a hawkish approach, the party vows in its platform to never retreat unilaterally from Israeli-held land – the way Israel left Gaza in 2005 – and that any “historic decision” concerning Israel’s foreign relations will be brought to a referendum, or to a Knesset vote subject to a special majority.

Finally, Gantz’s party has said it will retain the Jordan River as Israel’s eastern “security border” and also “enhance” the “settlement blocs” – meaning the Israeli communities in the West Bank that are adjacent to greater Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

While all this is engineered to attract traditional Likud voters, the party’s promise to expand public transportation on the Sabbath – which is currently highly limited due to long-standing politics arrangements with Israel’s religious parties – is meant to impress Labor voters in particular, and the broad middle class in general.

On a personal level, Blue and White’s most effective magnet for right-wing voters is Lt-Gen. (res.) Moshe Ya’alon, who thinks Israel should encourage a million new settlers to live in the West Bank, and who, last decade, lost his job as IDF chief of staff because he opposed former PM Ariel Sharon’s 2005 disengagement from Gaza.

The party’s tough on security image is further bolstered by Ya’alon’s subsequent role as Netanyahu’s defence minister, and by the presence on its ticket of Netanyahu’s former director of communications, Yoaz Hendel, and his former cabinet secretary, Zvi Hauser.

Yet Blue and White also includes Yael German, a former health minister whose political career began as a mayor on behalf of Meretz, the party to Labor’s left. She is not alone.

Blue and White’s administrative spine is supplied neither by Gantz nor by Ya’alon, but by their third partner, Yesh Atid (“There is a Future”), the centrist party that has already run in two general elections, and is headed by former TV news anchor Yair Lapid.

Other notable doves in Lapid’s party include Ofer Shelah, a former journalist who lost an eye while fighting in Lebanon as a company commander of the paratroopers.

Gantz risks getting lost amidst these many diverse personalities, having spent not one day in his 59 years as a minister, deputy minister, lawmaker, or even city councillor in a local municipality.

Blue and White also has an inconsistent approach on the economy. Yesh Atid is as conservative and free market-oriented as Netanyahu, which is why he and Lapid generally worked together well when the latter served as finance minister in Netanyahu’s government from 2013 to 2015.

However, by enlisting union leader Avi Nissenkorn, the chairman of the Histadrut labour federation, Gantz has muddied this economic identity. Netanyahu has made Nissenkorn’s recruitment a key political target in the election campaign, claiming the union leader will be Gantz’s finance minister and will steer the Israeli economy away from its capitalist present back to its socialist past.

Whatever this brew yields on April 9, for now Blue and White’s electoral goal of toppling Netanyahu looks likely to prove elusive.

Most polls suggest Gantz will win more votes than Netanyahu, predicting he will get some 25-29% of the vote, compared to 24-25% for the incumbent PM. However, smaller satellite parties of the Likud seem likely to garner enough votes to keep Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition intact and a governing coalition beyond the reach of Blue and White, likely leaving Gantz as opposition leader.

The most realistic scenario for Gantz to become prime minster is if Netanyahu’s legal situation – he is facing corruption indictments in three separate cases – causes his colleagues in Likud to replace him. A new Likud leader could then potentially join a national unity coalition with Gantz. For now, however, this prospect seems distant.

Polls now appear to indicate that Gantz’s arrival on the scene has merely rearranged the opposition vote, with his new party welding the votes formerly backing former Yesh Atid with nearly half the votes Labor won during the 2015 election, when it was called the Zionist Union.

Then again, this is also what some assumed back in 1965, when a similar welding happened between that era’s main centrist force, the Liberal Party, and the main party on the right, Menachem Begin’s Herut (“Freedom”) party. The new party they formed ultimately produced, with other parties, the Likud, which later replaced Labor as Israel’s hegemonic political force.

The Liberal Party, with which Begin allied, combined two previous centrist parties – the General Zionists and the Progressives – which together made up one-tenth of the first Knesset.

The two parties’ electorates were largely made up of the relatively well-off bourgeoisie who rejected both David Ben-Gurion’s economic socialism and Begin’s nationalist militancy. In Israel’s first years, this meant opposing Labor’s economic interventionism and refusal to separate religion and state, but at the same time backing Ben-Gurion’s historic and then-controversial Reparations Agreement with West Germany.

The combination of conservative economics and pragmatic diplomacy represented by these two parties originated in the legacy of Chaim Weizmann, the scientist-turned-statesman who, during World War I, helped craft the Balfour Declaration, and 32 years later became Israel’s first president.

However, unlike his rivals from the left and right, Ben-Gurion and Vladimir Jabotinsky, Weizmann did not personally get down to the business of cultivating his own political party. He preferred instead to fashion himself as the Zionist movement’s apolitical, high priest.

Weizmann was identified with the General Zionists, but the party did not fully benefit from his charisma and clout, the way Labor and the Revisionists benefitted from that of their own leaders.

Still, the electoral potential was there, and by 1951 the two centrist parties held one-fifth of the legislature. The pair’s subsequent disappearance within Likud gave rise to other centrist parties, some of which did remarkably well.

Most pivotally, in 1977, a party named Dash (acronym for Democratic Movement for Change), headed by world-renowned archaeologist and retired general Yigael Yadin, won 15 of the Knesset’s 120 seats. This outcome dealt Labor a blow that resulted in the Likud coming to power for the first time ever.

However, Dash split almost immediately after the election between a faction that joined the government and one that joined the opposition. By the next election the party had vanished.

A variety of centrist formations came and went over the next two decades, usually winning some 5% of the vote each. Last decade, however, two such parties achieved bigger things, in ways that might hint at the aftermath for Blue and White.

The first was Shinui (“Change”), led by journalist Tommy Lapid. The second was Kadima (“Forward”), formed by Ariel Sharon after he came to espouse unilateral territorial withdrawals and left the Likud.

Shinui was a small party when Lapid joined it, but with his charisma and a fiercely anti-clerical agenda, he won 15 seats (12.5% of the votes) in 2003 and became Sharon’s deputy PM and main coalition partner.

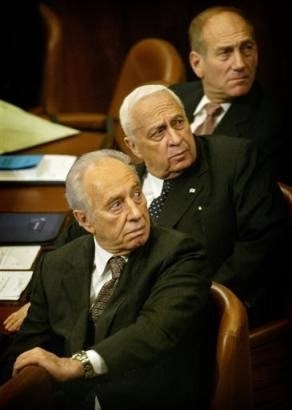

The Kadima leadership in 2005 (L-R): Peres, Sharon and Olmert

Kadima, however, would soon afterwards extinguish Lapid’s centrist comet.

Led by Sharon and his longtime arch-rival Shimon Peres, the new configuration appealed to a broad swathe of centrist voters, who liked the reincarnation of both political veterans as humbled ideologues: Sharon, the former settlement builder who now evacuated Gaza, and Peres, the great land-for-peace advocate who now joined a unilateral retreat that implied peace agreements with the Palestinians were unattainable.

Kadima ended up running without its founder, who fell ill. Even so, the party’s victory in 2006 under Ehud Olmert came fully at the expense of Lapid’s Shinui, whose entire electorate was pocketed by the new party. Seven years later, Kadima also became history.

Even so, the centrist electorate it represented remained available, and soon enough much of it was gathered up by Tommy Lapid’s son, Yair, and the Yesh Atid party that is now the most important component of Blue and White.

Further, Blue and White is not the first centrist “General’s party”. The Centre party which ran in the 1999 election was led by former IDF generals Yitzhak Mordechai and Amnon Lipkin-Shahak. While the party only won seven seats and afterwards quickly vanished from the political scene, it arguably cost Netanyahu that election, which saw Labor leader Ehud Barak become PM.

The bottom line of all this history is that Blue and White’s experiment is by no means novel, and its future, even if it wins a plurality of votes as polls currently predict, is precarious at best.

With the approaching vote being largely about Netanyahu’s legal situation and the attack he is waging on the judiciary, the centrist formation he faces requires today more than ever the kind of towering figure the Israeli centre never had; the kind of party leader Chaim Weizmann could have been, but refused to be. Benny Gantz has yet to prove he can become that figure.