Australia/Israel Review

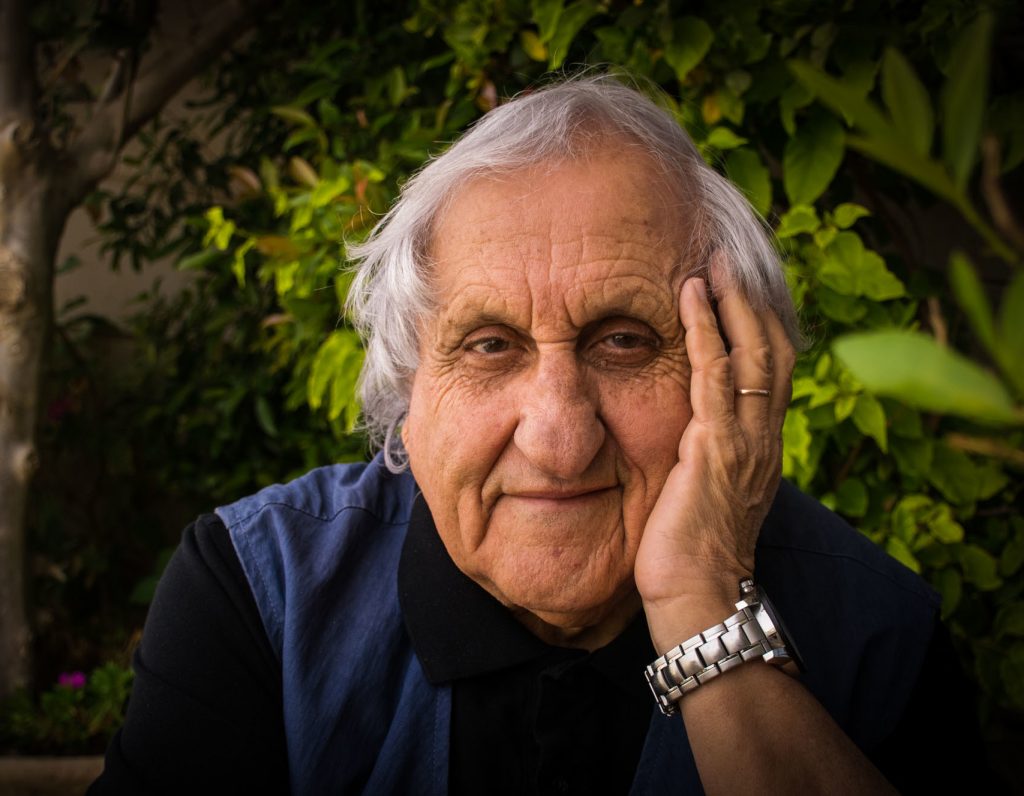

Bilio File: Israel’s last literary lion

Jun 30, 2022 | Amotz Asa-El

The passing of A.B. Yehoshua

The sun was approaching the Mediterranean horizon when hundreds gathered at the foot of Mount Carmel on June 15 to pay their last respects to the legendary Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua.

One of Israel’s most prolific, provocative and best-known writers, Yehoshua died on June 14 at 85 after a two-year battle with cancer. Even during this period, Yehoshua still published two books, the last works in a 30-volume corpus of novels, novellas, plays, essay collections and two children’s books.

As would befit a final leave-taking for a writer who had been a pillar of the public arena since the 1970s, the crowd included scores of novelists, poets, scholars and literary critics, and was led by former Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, Yehoshua’s close friend and political adversary of some 70 years.

Translated into 28 languages, and the winner of numerous awards, Yehoshua’s writing always tackled universally intelligible themes, like a teenager’s discovery of her mother’s infidelity (The Lover, 1977); a young doctor’s attraction to his boss’ wife (Open Heart, 1997); tensions between Christian and Muslim civilisations (A Journey to the End of the Millennium, 1999); incest (Mr. Mani, 1993); and ageing, loss and dementia (The Tunnel, 2020).

At the same time, his stories’ settings, heroes, language and undertones were quintessentially Israeli, as was their frequently didactic subtext.

Thus, for instance, in A Journey to the End of the Millennium, Yehoshua indirectly tackled relations between Israeli Jews from European and Middle Eastern backgrounds by travelling to an era when Christendom was underdeveloped and the Muslim world was advanced. It was Yehoshua’s way of telling Israel’s European elite that its currently dominant position is circumstantial and temporary.

Similarly, in A Late Divorce (1982), Yehoshua tackled the prickly issue of Yerida, Israeli emigration from Israel, through the character of Yehuda Kaminka. Kaminka abandons his wife, kids and country for an American lover. A slimy individual, Kaminka attempts to steal back a letter in which he forfeited his house from his hospitalised ex-wife, thus personifying the generic anti-patriot who actively chooses a rootless life in foreign realms.

Some of Yehoshua’s Israeli themes were more atmospheric than ideological, but still captured the Israeli zeitgeist.

In Open Heart, for instance, he followed surgeon Benjamin Rubin’s arrival in India to bring home his hospital director’s gravely ill daughter. While there, Rubin is transfixed by India’s magic, as has happened to thousands of Israeli backpackers for whom post-military-service adventure trips have become a rite of passage.

Even so, the ideological subtext in Yehoshua’s writing is pervasive and thinly veiled.

Most notably, in Yehoshua’s first novel The Lover (1977), an Arab teenager who works in a garage becomes secretly involved with the daughter of the Jewish owner. Besides this plot’s literary novelty, it also sought to humanise the Arab “other”, in line with the land-for-peace ideas that Yehoshua was preaching at the time.

Such literary choices reflected the opinionated novelist who had strong views about current affairs, both in Israel and abroad, and for whom political activism was a natural corollary to literature.

Public issues that burned in Yehoshua’s heart were the Arab-Israeli conflict, Israel’s social tensions and the Jewish people’s relationship with its land. His most acclaimed novel, Mr. Mani, ranged across 1982 Israel, Nazi Greece and British Palestine to Hapsburg Poland and Ottoman Greece, and viewed all Yehoshua’s favourite political themes through the lens of a dynasty that, like his own forebears, had centuries of history in Jewish Greece.

Yehoshua’s quest for Israeli-Palestinian peace led him to endorse a succession of Israeli political parties of the left, including Labor, Meretz and, back in the 1970s, Sheli, one of the first parties to demand the establishment of a Palestinian state. This stance sometimes made him controversial in Israel, though it does not seem to have affected his book sales.

Even more contentiously, Yehoshua provoked many diaspora Jews with his claim that a fully Jewish life was possible only in Israel, a charge he levelled repeatedly in public lectures, and also backed with a theory of psycho-history presented in a famous essay titled “Exile as a Neurotic Solution.”

Yehoshua’s tough version of Zionism, rejecting the validity of diaspora life, was fashionable in Israel’s early decades, but has since become uncommon, reflecting the growing demographic confidence of Israelis and their realisation that Jewish life in today’s Diaspora is quite different from what it was in the past.

However, with Yehoshua’s passing, Israel lost not only a particularly provocative and brilliant author, but the very phenomenon of the politically active literary lion.

Israeli novelists and poets have often been politically focussed, vocal and influential since the state’s establishment.

Poet and playwright Natan Alterman (1910-1970) had a weekly column in Labor’s (long defunct) daily Davar, which the entire political class, along with the rest of the Israeli elite and much of the middle class, read every Friday. Alterman was identified with the Labor establishment and was a personal friend of David Ben-Gurion.

His contemporary, novelist Yizhar Smilanski (1916-2006) actually served as a lawmaker in David Ben-Gurion’s faction while penning his magnum opus, Days of Ziklag (1958), a depiction of 1948’s warriors in the Negev Desert, widely considered a foundational work about the first Israelis.

Across the aisle in the Knesset’s first years sat poet Uri Zvi Greenberg, who represented Menachem Begin’s Herut party and was one of the greatest poets of the Zionist revival.

Later, following the 1967 Six Day War, Israel’s poets and novelists largely sparked and dominated the debate over the war’s territorial outcome.

Three months after that war, in which Israel gained control over the Sinai Desert, West Bank, Gaza and Golan Heights, a group of writers led by Nobel Laureate S.Y. Agnon, Alterman and Greenberg – joined by eight other prominent writers – dominated a petition that called on the government to retain the newly conquered lands.

The opposite view was much less popular in those heady days, but it was also voiced by writers, first and foremost by Amos Oz (1940-2018), who penned a famous article calling on Israel to announce that, in return for peace, it would return the territories to Arab rule. Oz, 27 at the time but already a best-selling writer widely recognised as having great literary promise, was soon joined by his close friend Yehoshua, then 31.

The political balance among the literary class changed in subsequent years, as those who espoused annexing the territories passed away and some, most notably poet Haim Guri (1923-2018) moved from the right to the left (yet the right still had its fair share of literati, most notably novelist Moshe Shamir, songstress Naomi Shemer, who penned the iconic “Jerusalem of Gold”, and satirist Ephraim Kishon).

Whatever their belief system, the literati mattered, took sides and provoked debate and controversy. In 1988, during the First Intifada, Oz, Yehoshua, poet Pinchas Sadeh and historian Amos Eilon published a letter in the New York Times in which they called on American Jewry to publicly intervene in Israel’s internal debate concerning the Palestinian problem, arguing that by keeping silent they were effectively taking sides.

That was then.

Today, Israel’s writers mostly shun the political fray. Yes, there still is David Grossman, who now succeeds Yehoshua as the doyen of Israeli novelists, and like him has been an outspoken land-for-peace advocate since penning “The Yellow Wind”, a 1987 essay that, a few months before the outbreak of the First Intifada, warned of an approaching Palestinian explosion.

However, the rest of Israel’s best-known writers maintain a low political profile. Popular writers like Eshkol Nevo, Etgar Keret, Zeruya Shalev and Nir Baram make no political statements, join no political parties and don’t endorse political candidates. Even Meir Shalev, who voices left-wing views in his weekend column in Yediot Aharonot, shuns political activism and his novels avoid Israel’s political dilemmas.

The reasons for the literati’s retreat from politics are unclear. It may reflect the declining interest of many Israelis in politics. It may be about literature’s global crisis in an era where the printed word struggles to compete with online temptations. Or it may be a product of disillusionment with failed political gospels like land for peace.

Yehoshua himself, incidentally, eventually lost faith in the “land for peace” formula. At age 82, after half a century of preaching that idea, he wrote that the two-state solution had become impractical, due to both nations’ sweeping claims to the land they dispute and demographic developments that made an Israeli retreat all but impossible.

Yehoshua’s new proposal was that Israel and the Palestinians jointly form a bicameral federation.

There was a time when such an ideological rethinking by a major literary figure would be a big story, but that was last century. Though the new plan didn’t pass unnoticed, it was largely ignored. Times, evidently, really have changed.

And as for the plan’s details and prospects, as Yehoshua himself would say, that’s a story for another day.

Tags: Israel