Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: An 804-day nightmare

May 5, 2022 | Naomi Levin

The Uncaged Sky: My 804 days in an Iranian Prison

Kylie Moore-Gilbert, Ultimo Press, 2022, 416 pp., A$35

An oft-overlooked aspect of Australian academic Dr Kylie Moore-Gilbert’s false imprisonment by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is the actual charges she was convicted of.

Dr Moore-Gilbert was sentenced to ten years in jail for “cooperation in espionage for the tyrannical Zionist regime,” or in plain language, spying on behalf of Israel.

This is a truly unbelievable charge to level against a University of Melbourne lecturer who travelled to Iran in September 2018, after being invited – and receiving clearance from the University of Melbourne – to attend an academic conference in the holy city of Qom.

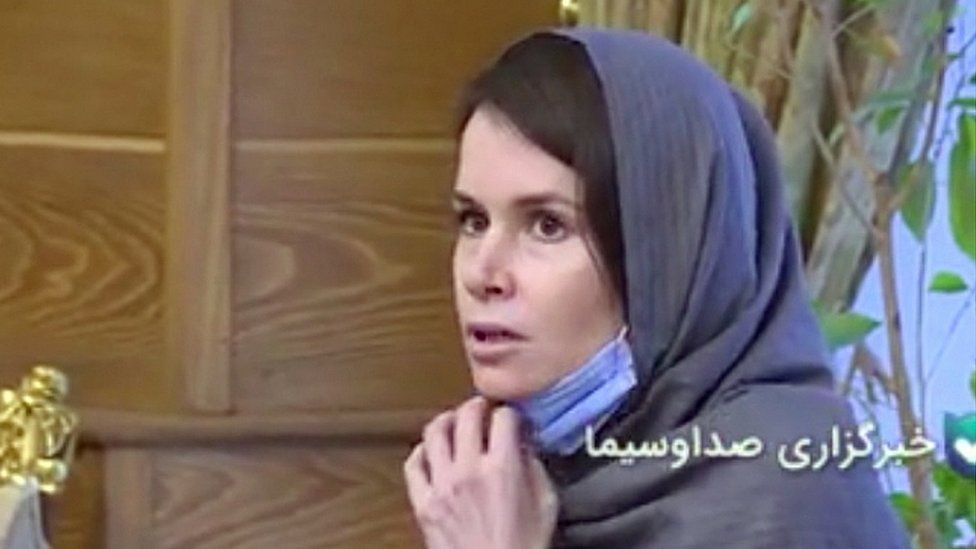

Dr Moore-Gilbert was arrested at Teheran’s airport and spent 804 days in an Iranian prison, including unimaginable months in solitary confinement. After much political game-playing, a complex diplomatic arrangement was negotiated involving the swap of Dr Moore-Gilbert for three IRGC operatives convicted of plotting a terrorist attack against Israeli diplomats in Thailand.

A memoir of her imprisonment, The Uncaged Sky: My 804 Days in an Iranian Prison, was published in late March by Ultimo Press.

This important book adds to the growing library of first-hand evidence of the cruelty of one of the Iranian regime’s favourite diplomatic tools – hostage diplomacy. From Barry Rosen, who in 1979 was one of 52 Americans detained in the US Embassy in Iran for 444 days, to Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian, who was detained on false charges in 2015 for 544 days, numerous victims have bravely put their experiences into words to draw attention to Iran’s brutal and blunt instruments of diplomacy.

Moore-Gilbert also uses her new book to raise awareness of the plight of her former fellow inmates, some of whom became genuine friends. These include Niloufar Bayani and Sepideh Kashani, Iranian conservationists who remain in prison after being falsely convicted of espionage; Fariba Adelkhah, a French-Iranian anthropologist who remains imprisoned more than 1,000 days after her arrest; Soheila Hijab, who has been jailed for 18 years for campaigning for women’s rights; and Nasrin Sotoudeh, an Iranian human rights lawyer sentenced to 38 years in prison and 148 lashes.

The Uncaged Sky: My 804 Days in an Iranian Prison is fearlessly and warmly written. As readers are confronted with the details of the author’s ordeal, they cannot help but wonder whether, if placed in the same situation, they would act with the courage and strength shown throughout by Dr Moore-Gilbert.

While initially shocked at her arrest, Dr Moore-Gilbert soon realised she was in real trouble. She writes: “The IRGC considered a person to be guilty from the moment the decision was made (by them) to admit him or her into prison for interrogation. The court, the trial, the judge – they were all mere rubber stamps. There was no presumption of innocence.”

The book goes on to provide unprecedented insight into the inner workings of the secretive IRGC, as well as some remarkable revelations into how Iranians view Israel and the Jewish people.

Early in the saga, her IRGC interrogators – who Moore-Gilbert labels a “morally corrupt Islamist mafia” – discovered she was married to a Russian-Israeli man, speaks Hebrew and had spent time studying in Israel. This information was like a red rag to a bull. Iran’s leaders have openly stated they would like to see Israel destroyed and the country targets Israel militarily via proxies including Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza.

The IRGC spent months trying to cut deals with Dr Moore-Gilbert. Initially, they asked her to lure her husband to Iran. She resisted, knowing this was a trap. The IRGC then changed tack, trying to convince her to use her “cover” as an Australian Hebrew- and Arabic-speaking academic to spy on Iran’s behalf. Again, she steadfastly refused.

Most of her incarceration was spent in the notorious 2A wing of Evin Prison – an area controlled not by Iran’s criminal justice system, but by the IRGC, specifically for political prisoners. For a short time towards the end of her ordeal, she was moved to Qarchak Prison where she mixed with other inmates. One she met was a woman called Marzieh who had been jailed for the “crime” of calling a person in Israel on Skype and posting pro-Israel comments on social media.

In Evin Prison, a senior IRGC interrogator – a man who calls himself Qazi Zadeh, but who Dr Moore-Gilbert discovered is actually named Lashgarian – tried to strike up a friendship with her. From him, we discover a great deal about Iranian views regarding Israel and Jews.

‘If there’s somewhere you don’t want us to bomb in Israel tell me. We can make an exception.’ Qazi Zadeh was sitting close to me, his eyes locked on mine. This was flirty banter, Rev Guards style. ‘Our Supreme Leader says in fifteen years’ time we’ll be praying at Al Aqsa Mosque [on the Temple Mount]. If you have an address for your husband’s family, give it to me and I’ll make sure it’s not targeted.’

The interrogator then asked Moore-Gilbert “Whether the ‘evil Zionist lobby’ in the US, funded by the ‘uber-rich Jewish puppets of the settler movement’, controlled all of US policy or just Middle Eastern policy?”

During one of these lengthy interrogations, Qazi Zadeh/Lashgarian finished his questioning by asking his offsider, Mohandas, to show their prisoner some CCTV footage. Moore-Gilbert was astonished to see him bring up real-time security footage from a Tel Aviv art museum. She asked why the IRGC had hacked into the art museum’s security cameras. Mohandas replied “for fun” and Qazi Zadeh/Lashgarian added, “in fifteen years we will be there.”

Another time, Qazi Zadeh/Lashgarian opened an Israeli newspaper on his phone and asked Dr Moore-Gilbert to translate. On that day, Yaakov Litzman, then Israel’s Minister for Health, had contracted COVID-19. The response from the IRGC interrogator – who Dr Moore-Gilbert had already explained to readers believed COVID-19 to be a Western conspiracy – was, “Maybe the Jews will wipe themselves out in the end, and we won’t have to do it for them!”

The conversation continued:

‘I’ve heard that the Jews actually killed Jesus and that in Europe they used to drink the blood of Christians during some of their festivals,’ Qazi Zadeh said.

I looked at him in disbelief. There was no malice in his voice or expression. He didn’t seem to be trying to provoke me.

‘That’s absolutely not true,’ I said firmly. ‘Those are antisemitic conspiracy theories.’

‘Well it’s true that the Jewish lobby in the United States controls the world through international finance, and that no American can be elected president without Israel’s support,’ he retorted.

As the interrogation ended, Qazi Zadeh/Lashgarian told Moore-Gilbert these are the official stances of his organisation, the organisation that is directly responsible for protecting the Islamic revolution in Iran.

A marathon diplomatic effort, spearheaded by Australia’s Ambassador to Iran Lyndall Sachs and Nick Warner, the former director-general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and Office of National Intelligence, saw Moore-Gilbert flown back to Australia on November 25, 2020.

In the book’s epilogue, Dr Moore-Gilbert writes that her captors were “complex human beings”, not just two-dimensional manifestations of the brutal Islamic Republic. While a few of her captors showed compassion, others, like the IRGC judge who sentenced her, are “truly evil people”. She finishes with commentary on Iran’s brutal human rights violations, including its obsession with “hostage diplomacy”:

[Hostages] are cynically used as pawns by a regime which has few other cards to play to secure its interest on the international stage. However, we are only the tip of the iceberg. The regime has long persecuted civil, political and women’s rights activists, as well as member of religious minorities such as the Baha’i.

Moore-Gilbert concludes with the following message: “We who live in freedom must speak out for those who are still struggling for the everyday liberties we too often take for granted.”

Tags: Australia, Iran, IRGC, Kylie Moore-Gilbert