Australia/Israel Review

A Return to the Rabin Doctrine?

Feb 28, 2020 | Dan Diker

Much has already been written about the US Administration’s “Vision for Peace” in the Middle East published on Jan. 28. Most commentary has focused on the unprecedented US recognition of Israel’s legal rights east of the 1967 lines and, simultaneously, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s willingness to operationalise his 2009 Bar Ilan University speech supporting a two-state resolution.

In Washington, Netanyahu acceded to the establishment of a sovereign demilitarised Palestinian state in some 70% of the disputed West Bank, located in the centre of the West Bank, the heart of Israel’s biblical homeland.

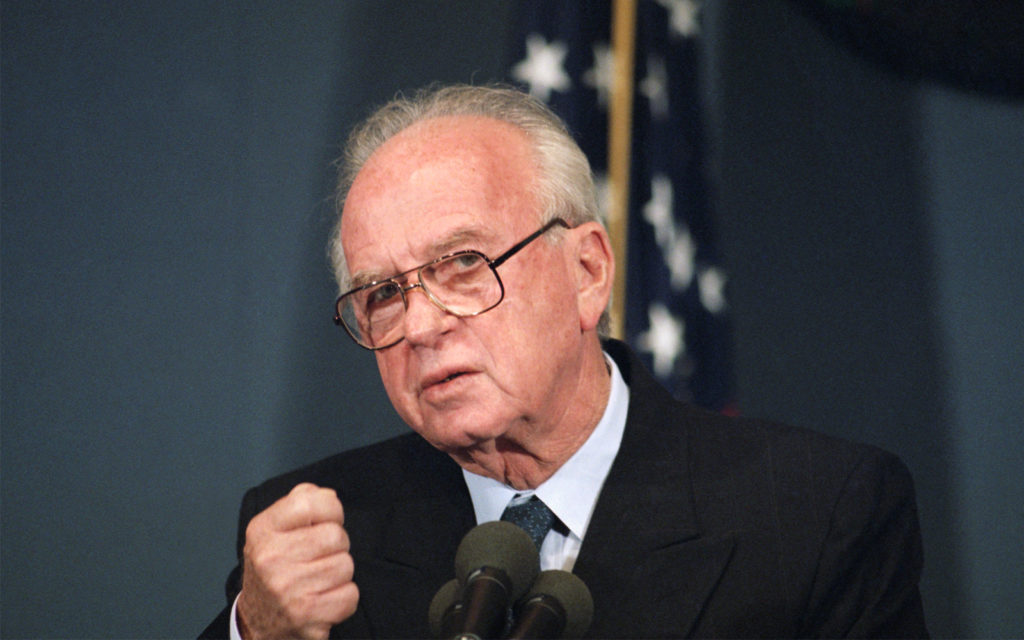

However, few observers have recognised the major paradigm shift that the US Administration’s peace plan signals in the long and largely failed history of Palestinian-Israeli diplomacy: a return to the security-first approach of the late Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and specifically, the concept of defensible borders.

The US plan should be closely compared to Rabin’s defensible borders approach to the Oslo Peace Accords that were first signed at the White House in 1993, and then detailed in the 1995 interim accord between Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, under the stewardship of US President Bill Clinton.

On Jan. 29, 2020, the day after the Trump peace plan was published, Shimon Sheves, former Director-General of Prime Minister Rabin’s office and one of his closest advisors, told Israel’s Army Radio’s evening news program, “The Trump plan is essentially the Rabin plan.” While critical of Prime Minister Netanyahu’s unilateral acceptance of the plan, Sheves still noted that the Trump plan is a “continuation of Rabin’s legacy.”

Similarly, Ben Caspit, one of Israel’s leading journalists, and known for his unrelenting criticism of Netanyahu, penned a generally positive assessment of the Trump plan in the Maariv daily, calling it “a modern incarnation of Rabin’s plan from 25 years ago.”

What were the principles behind Rabin’s defensible borders approach to Oslo that today anchor the US Administration’s approach to a peace deal with the Palestinian leadership?

Rabin had presented his vision of a final status peace deal during the ratification of the Oslo Interim Accords at the Knesset on Oct. 5, 1995, just three weeks before his tragic assassination. Speaking from the Knesset podium, Rabin told the packed plenum, “The borders of the State of Israel during the permanent solution will be beyond the lines that existed before the Six-Day War. We will not return to the June 4, 1967 lines.”

It should be noted that since 2017, when the Trump plan was initiated, US peace interlocutors undertook a two-year “listening tour” in Israel and the Middle East, and had been advised that Rabin, in line with every Israeli prime minister since the fateful days of the 1967 war, had rejected an Israeli return to the unstable and indefensible pre-1967 war lines, providing an important point of reference for the current US vision. Former Foreign Minister Abba Eban had famously referred to the pre-1967 lines as “Auschwitz borders.”

In 1995, Rabin further declared to the Knesset plenum, “The security border of the State of Israel will be located in the Jordan Valley in the broadest sense of that term.” And serving as a precursor to the Trump vision, Rabin also emphasised that Jerusalem would remain Israel’s united capital.

The Doctrine of Defensible Borders

Rabin’s insistence, 25 years ago, on Israeli control of the strategically vital Jordan Rift Valley, was an antecedent to Trump’s proposal of Israeli sovereignty in the Jordan Valley, both of which were rooted in the doctrine of defensible borders.

The Israeli strategic doctrine of defensible borders at Oslo, now readopted in the Trump proposal, constituted a return to a “security first” approach to peace negotiations. This term was referenced by former Defence Minister and IDF Chief of Staff Moshe “Bogie” Yaalon following several failed attempts at reaching diplomatic agreements with the Palestinians.

These Israeli peace proposals, beginning with former Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s offer at the Taba Summit in 2001, had shelved the defensible borders approach in favour of the far riskier plan of “security arrangements,” which Palestinian negotiators also rejected.

The US re-adoption of Rabin’s defensible borders doctrine also helps explain why Yaalon’s fellow leaders of the Blue and White Party, former IDF Chiefs of Staff Benny Gantz and Gabi Ashkenazi, also embraced the Trump plan’s call for Israeli sovereignty over the Jordan Valley and the northern Dead Sea basin in the context of the overall vision. Notably, both Gantz and Ashkenazi have even incorporated Rabin’s nomenclature, calling for the Jordan Valley to be Israel’s “eastern security border.”

Some commentators have mistakenly focused on the issue of settlements intertwined in the Trump plan’s proposal for the Jordan Valley. However, the Jordan Valley is one of the least populated areas in the West Bank and only includes some 5,500 Israeli residents, and approximately three percent of the West Bank Palestinian population. That is why the strategic importance of the Jordan Valley has been emphasised by Israel’s political and military leadership since 1967 – including the leadership of both major political parties.

The defensible borders concept that Rabin embraced was first formally outlined as a national security plan following the 1967 war by Gen. Yigal Allon, Rabin’s commander in the pre-state Palmach strike force, who subsequently served as Rabin’s foreign minister. Allon emphasised the importance of defensible borders to Western audiences in a 1976 issue of Foreign Affairs. He posited that Israel needs to retain a topographical barrier to defend itself from attacks from the east, a move that would constitute an additional defensive measure beyond insisting on the demilitarisation of Palestinian independent areas or, in today’s terms, a proposed sovereign Palestinian state.

Allon and Rabin were particularly concerned at the prospect of hostile forces, and today terror groups or individual terrorists, firing rockets and anti-aircraft weaponry from the hilltops of the steep 975-metre high West Bank mountain ridge. That ridge overlooks Israel’s narrow coastal plain that contains Israel’s major cities, 70% of Israel’s residents, 80% of its industrial capacity, major highways and infrastructure, and particularly, Israel’s major airport.

Allon had insisted on Israel annexing the entire Jordan Valley, including the hilly terrain facing eastwards toward Jordan as well as the valley below, constituting some 33% of the West Bank. This is virtually identical to the 30% of the territories the US plan calls for today to remain under Israeli sovereignty. While Rabin had been less specific about annexing the entire area, the Allon plan, Rabin’s security doctrine at Oslo, and the current US plan are all anchored in the concept of defensible borders. They saw that the Jordan Valley and the adjoining eastern hill ridge formed a natural topographical security wall that would protect Israel’s main airport and Mediterranean coastal cities from rocket, mortar, and anti-aircraft assault by terrorists firing down from West Bank hilltops.

Rabin’s Oslo plan opposed Palestinian sovereignty. Rabin told the Knesset plenum, “We would like this to be an entity that is less than a state, and which will independently run the lives of the Palestinians under its authority.”

The Trump plan’s defensible borders concept for Israel is anchored in proposed Israeli sovereignty in the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area. In contrast, Rabin had envisioned an Israeli “security border” in the Jordan Valley, which did not require full Israeli sovereignty. Israeli defensible borders notwithstanding, the current US plan, departing from Rabin’s vision of Palestinian autonomy, also establishes a blueprint for a sovereign Palestinian state, with a land connection to Gaza and additional swapped sovereign territory in the Western Negev. For his part, Rabin had sought to maintain an Israeli security presence and Jewish communities in parts of Gaza. Rabin also did not entertain land swaps from pre-1967 Israel.

Why Six Negotiating Experiences Failed

While defensible borders anchored both Oslo and the current US plan, the past 25 years have witnessed six failed attempts by three US presidents to reach a peace agreement between the Palestinian Authority and Israel since the signing of the Oslo Exchange of Letters in September 1993. In each instance, the Palestinian leadership turned down US-mediated offers for sovereign independence. The Palestinian rejections of diplomatic compromises included: Clinton’s Camp David Summit in 2000, the Taba talks in 2001, US President George W. Bush’s Road Map in 2003, the US-brokered Israeli Gaza withdrawal in 2005, the Annapolis peace summit in 2008, and the Kerry peace initiative under President Barack Obama in 2014.

The US Administration’s latest approach, therefore, has shifted the paradigm for peace by recognising Jewish historical and legal rights to sovereignty on both sides of the 1949 armistice lines in the context of the overall plan, thereby eliminating the false international assumption that the Palestinians exclusively possess legal rights in the disputed territories.

Second, the Trump peace plan’s re-adoption of Israel’s national consensus doctrine of defensible borders for Israel via the proposed application of Israeli law over the Jordan Valley, as part of the overall plan, will enable Israel to secure its sovereignty while enabling Israel to “defend itself by itself.”

This ironclad national security principle has always been an essential Israeli pre-condition to making any substantial concessions and taking significant additional risks for peace. Today, with the publication of the US plan, Israel is taking unprecedented risks in considering the prospect of living next to a sovereign Palestinian state, particularly in a Middle East region that is plagued by radical regimes, proxy forces, political instability, and failed states. That is why defensible borders are critical in providing the essential protections that are a guarantor of an Israeli-Palestinian peace that will be lasting and durable.

Dan Diker is a foreign policy fellow at the Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs and a research fellow at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism at IDC Herzliya. © Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs (www.jcpa.org), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians, Yitzhak Rabin