Australia/Israel Review

A Forgotten Conflict

Oct 27, 2009 | Bren Carlill

Bren Carlill

It’s a country where the slogan of one of the major players is “Death to Israel!” but it’s not Iran. Where oil is running out, and the regime’s survival is questioned, but it’s not Syria. Where Saudi Arabia and Iran are backing opposing sides in a Sunni-Shi’ite showdown, but it’s not Lebanon. Al-Qaeda is resurgent there, but it’s not Afghanistan.

It’s Yemen. And its increasing fragility casts a long shadow over the Middle East. Al-Qaeda’s presence there, and its access to vital oil infrastructure and shipping lanes potentially threatens key Western interests. Yet the situation is almost completely unreported in the West.

A short history illustrates how Yemen’s problems came about, why they are so deeply engrained, and why a failure to resolve them has the potential to cause further regional instability.

The Ottoman Empire extended formal control over the whole area of Yemen until 1839, when the British established a colony in the southern section. In 1967, this became South Yemen which, two years later, was overrun by Marxists.

In 1918 the Ottoman Empire relinquished its suzerainty over Yemen’s north. Zaydis, a Shi’ite sect, had ruled the area for a thousand years, and these became the rulers of the new state of North Yemen.

A 1962 revolution overthrew Zaydi rule. Since then, Zaydis have claimed the government has not invested in much needed infrastructure in their areas, centred on the northern city of Sa’ada, just south of the Saudi border.

Theological differences between the country’s Sunnis and Shi’ites have been better handled. State educational efforts have attempted to smooth over many aspects of the doctrinal divide, allowing peaceful Sunni-Shi’ite co-existence.

Despite some tension, North and South Yemen maintained relatively friendly relations. In 1972, the two countries agreed to unite and, after a few aborted attempts, this happened in 1990. North Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, became the capital of the united country. Four years later, a secessionist movement in the south – the remnants of the Marxist leadership – sparked a short-lived civil war, which the north quickly won.

Most of Yemen’s oil facilities lie in the south. Many southerners suspect that this was the only reason northerners pursued unification. Tension has been steadily increasing. An opposition rally, held in April this year to mark the 15th anniversary of the civil war, became violent, leading to the death of eight people and the central government temporarily closing down seven newspapers.

Despite the increasing government repression of dissent, Yemen remains much more democratic than its neighbours. Although President Ali Abdallah Salih came to power undemocratically in 1978, he won free and fair elections in 1999 and 2006.

The tension in the south notwithstanding, Aish Awas of the Sheba Centre for Strategic Studies, a Yemeni think tank, does not believe the current violence will lead to another civil war. In 1994, Arab states supported separatists. Today, all support Yemen’s unity. There are two main reasons for this difference.

When Iraq occupied Kuwait in August 1990, President Salih was one of the few Arab leaders to back Saddam Hussein. This earned the enmity of adjacent Arab countries, who expelled Yemeni foreign workers from their countries, and backed the separatists four years later.

But today, the threat that al-Qaeda poses – and its talent for manifesting itself in under-governed Muslim-majority areas – leads regional governments to believe it imperative that all countries in the region remain stable and able to effectively govern territory nominally under their control.

This is why Saudi Arabia is trying to shore up Yemen’s viability. Last year it granted work visas for 130,000 Yemenis, and has signed contracts to build numerous hospitals in the country. Other Gulf states have also committed themselves to improving Yemeni infrastructure.

However, this might be too late. Yemen faces a number of serious shortages. Oil is the source of almost three-quarters of Yemen’s public revenue. Unfortunately, lower production in recent years has been coupled with a fall in oil prices. In the first seven months of this year, Yemen earned US$803 million, down from US$3.12 billion during the same period last year. Moreover, experts predict the country’s oil reserves will run out in ten years’ time.

An even more serious concern is water. Yemen receives little rainfall, sourcing most of its water from artesian aquifers. Water is also expected to run dry in ten years. Worse, most of Yemen’s arable land – and a third of its annual water use – is dedicated to growing Khat, a mild amphetamine-like stimulant widely used in Yemen.

The two-thirds of Yemen that are ungoverned, the porous Saudi border, the relatively unhindered access to Saudi oil facilities and access to shipping lanes in both the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea have foreign analysts worried about the prospect of a powerful al-Qaeda presence in the country.

The Times reported in October that al-Qaeda is recruiting poverty-stricken Yemenis, who make up about 35% of the population. The same article reported that hundreds of al-Qaeda fighters from Afghanistan and Pakistan have entered Yemen in recent months. Numerous foreigners have been kidnapped, and some killed. Approximately 100 Yemeni citizens remain interned at Guantanamo Bay, with America unwilling to release them, fearing Yemen will be unable to deal with them. Confirming American fears, in February, a former Yemeni Guantanamo Bay prisoner announced the merger of the Saudi and Yemeni branches of al-Qaeda to become ‘al-Qaeda of the Arabian Peninsula.’

That led US Director of National Intelligence Dennis Blair to suggest Yemen is “re-emerging as a jihadist battleground and potential regional base of operations for al-Qaeda to plan attacks, train terrorists and facilitate the movement of operatives.”

However, Princeton University’s Gregory Johnsen told TIME in October, “The Yemeni government is much more concerned with fighting the [Zaydi] Houtis in Sa’ada and with the secessionists in the south. Al-Qaeda ranks a distant third. The government doesn’t see it as a Yemeni problem [but rather] a foreign problem.”

The attempts by the North Yemen government after the 1962 revolution to smooth out Sunni-Shi’ite differences – by pushing a secular agenda for the whole country – were initially successful. However, a backlash developed last decade, with revivalist Zaydis demanding their cultural and religious identity be preserved.

The Zaydi nationalist movement is led by the Houti clan. The movement claims the government is deliberately attempting to wipe out Zaydi identity. Moreover, Zaydi rebels – who have since come to be known collectively as Houtis – claim the government is actually beholden to Sunni Wahhabi influence.

In recent years, Sunni Yemenis have also become more religious, despite the government’s efforts. Many point to Saudi Arabia’s influence. Key Wahhabi figures have come from Yemen’s northern neighbour along with Saudi largesse.

For its part, Yemen claims the Houtis are attempting to establish a Shi’ite state in the country’s north, and that Iran is behind both the radicalisation of the Zaydi population and the subsequent uprising.

Both Iran and the Houtis deny Iranian involvement, and there is little concrete evidence to support the claim. However, Yemeni officials have claimed the army has captured from Houtis money and weapons donated by Iran.

Regardless of the lack of evidence, a Houti uprising is in Iran’s interest. To have a Shi’ite rebellion on the Saudi border is a plus. And if they were successful, Houti – and thus Iranian – access to the Red Sea would be a major benefit.

As a report from the Intelligence and Terrorism Information Centre (ITIC), an Israeli NGO, pointed out, Iran frequently interferes in other countries’ affairs (for instance, its recently exposed efforts in Egypt), though typically denies doing so.

Indeed, the ITIC notes that a Hezbollah website provides the Houtis with a discussion forum to list the achievements of the rebels against the Yemeni army and advertise their radical Islamist ideology. That Hezbollah, itself an Iranian sponsored organisation, hosts a Houti propaganda site, is “additional proof” of Iranian support for Houti rebels, according to the ITIC.

More evidence is the Houti slogan – ‘God is great! Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse upon the Jews! Victory to Islam!’ – considered by many to be typically Iranian.

This anti-American, anti-Israel slogan has allowed the Yemeni government to effectively portray itself as on the West’s side in the war on terrorism, giving it a free hand to deal with the Houti challenge as it sees fit. The alleged Iranian influence is another reason why Arab countries have strongly backed Yemen.

Houtis and Iran have accused Saudi Arabia of using its air force to bomb Zaydi areas. Both sides accuse the other of indiscriminately targeting civilians and using child soldiers.

The result of five years of on-again-off-again warfare is 150,000 internally displaced people, of whom only about 75,000 are in camps administered by foreign aid organisations.

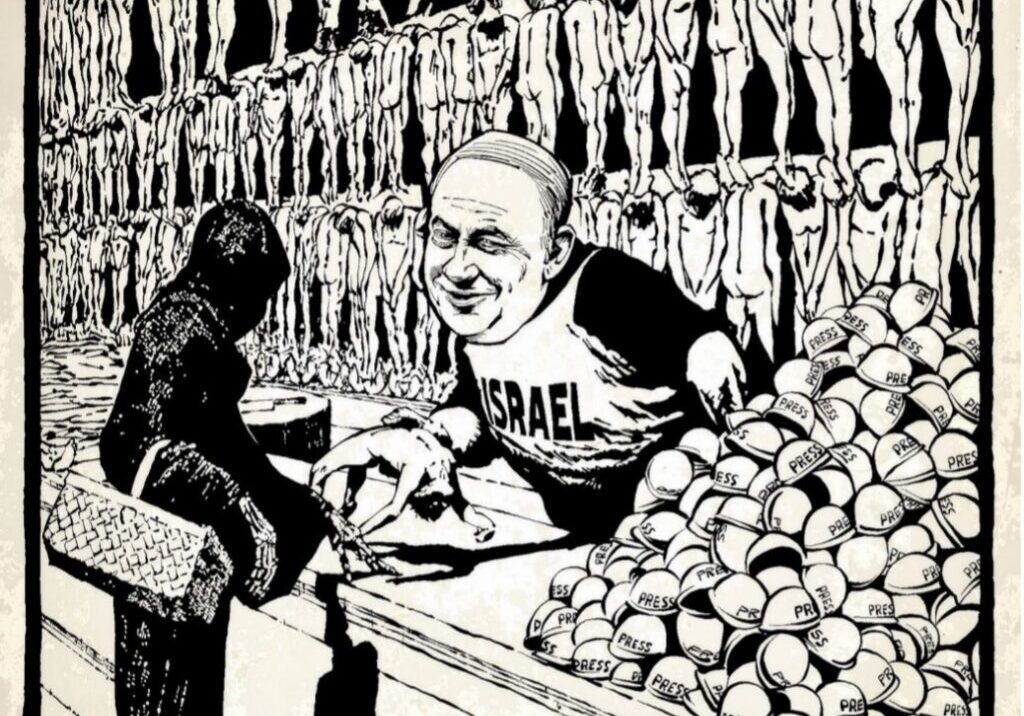

The government has blocked access to the battle area to aid organisations and journalists, and has also blocked mobile phone signals. Sa’ada, the main Zaydi town, has been besieged since the fighting restarted in earnest in August this year.

To complicate matters, the government pays local tribes to take part in its campaign. This has resulted in those tribes’ traditional rivals taking up arms to support the Houtis, thereby further widening the conflict.

Though Yemen lacks resources, its proximity to important shipping lanes and Persian Gulf countries renders it vital that it not fall to al-Qaeda. Unfortunately, the uncertainty in the north and south, the entrenched poverty and the openness to outside influence makes it appear the country is slipping out of central control, and could be destined to become another Afghanistan in the Arab heartland.

Adam Reynolds, a photojournalist based in Yemen, contributed to the research for this story.

Tags: Islamic Extremism