Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: Hiding in plain sight

Dec 19, 2025 | Julie Szego

The monsters we let dwell amongst us

Nazis in Australia: The Special Investigations Unit, 1987-1994

Nazis in Australia: The Special Investigations Unit, 1987-1994

Edited by Mark Aarons & Graham Blewitt

Schwartz Books Pty Ltd, 2025, 367 pp. $33.99 [purchase here]

Though I’ve lived all my life in Melbourne, I didn’t know about the monsters hiding in plain sight at Fawkner Cemetery in the city’s north. There lie almost 300 members of the notorious Latvian and Estonian SS Legions – volunteers in the Nazi-controlled death squads of 1943 to 1944.

One of the deceased, Karlis Ozols, directed the mass murder of 30,000 Jews and others. To take just one episode in his short but blood-stained career: in a forest outside of Minsk, truckloads of women were ordered to strip naked. Herded to the edge of a pit where two dozen men stood smoking and swigging from their vodka bottles, each was shot with a single bullet to the back of the head.

So unnerving was Ozols’ brutality, even the German SS described him and his men as, “a wild, almost bestial horde.”

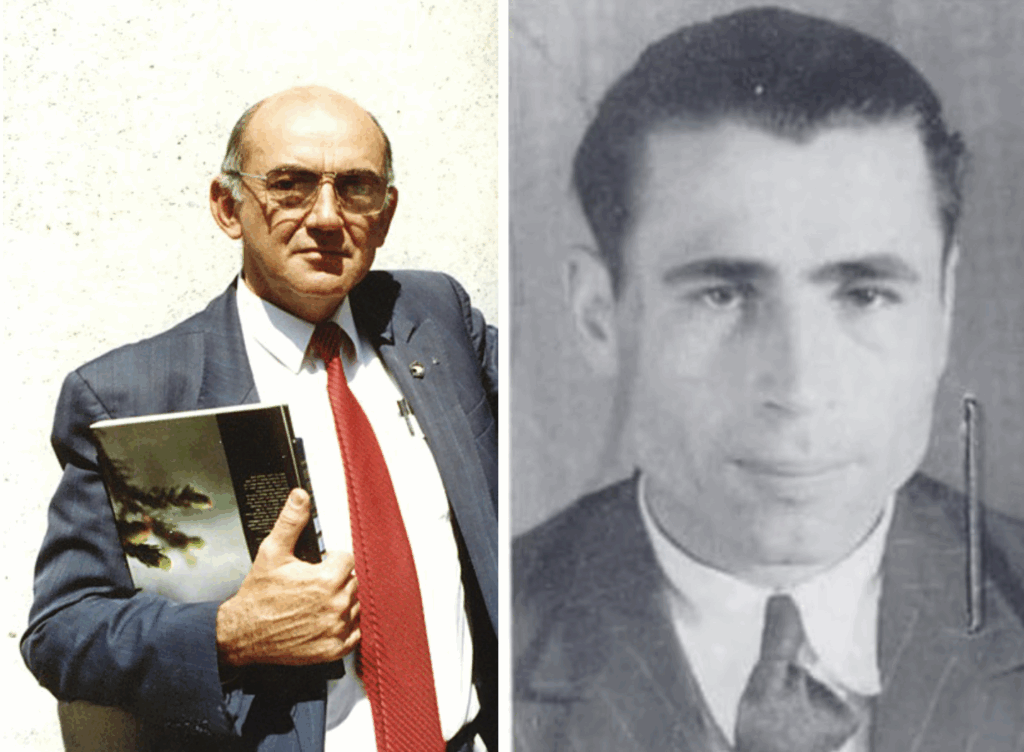

Both Ozols and Fawkner Cemetery feature in a photographic inset midway through Nazis in Australia, a compilation of essays that tell the story of Australia’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU), set up by the Hawke Government. Between 1987 and 1994 the SIU’s tenacious professionals hunted the war criminals who had settled here after World War II.

Ultimately, they failed. All the Nazi war criminals in Australia died as free men. Thereafter, the Keating Government, citing high costs and paltry results, shut the unit down.

So, was all the effort for nothing? This is the question that animates the book.

The SIU was set up on the recommendations of an inquiry sparked by ABC investigative reporter Mark Aarons’ landmark series, “Nazis in Australia”.

In his foreword, Aarons recalls a conversation with Bob Greenwood QC, the head of the newly-established unit. Attorney-General Lionel Bowen had given Greenwood a choice between conducting an inquiry with the powers of a royal commission or pursuing criminal convictions.

“With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight,” Aarons reflects, “it might have been more effective if Bob had taken up the first option [an inquiry]. While the pursuit of justice might not have been served, the laying down of the facts was vital.”

Among the facts that have long exercised Aarons is how Nazi war criminals came to migrate to Australia in the first place. Immigration officials had turned a blind eye to dubious pasts at a time when the national ethos was one of “populate or perish”. Worse, some war criminals were recruited as anti-Soviet informants for ASIO.

Greenwood carried in his wallet a photograph showing the remnants of corpses in a mass grave excavated by the SIU. Asked why he took on the task of leading the unit, he’d would point to the photograph and say, “That’s why!” He died in 2001, and the book is dedicated to him.

The SIU examined 841 cases. Three suspects were identified as meeting the evidentiary threshold for charges. In the end, only one stood trial: Ivan Polyukhovich, a former forest warden in the Ukrainian village of Serniki.

As a consequence of adverse pre-trial rulings against the prosecution, an initial 13 charges against him were whittled down to two counts: the murder of a Jewish woman known as “the miller’s daughter” and her two children in either August or September 1942; and being “knowingly concerned” in the murder of between 553 and 850 of Serniki’s Jews.

Michael Wolf, a former deputy director of the American counterpart to the SIU and consultant to it, asks in his contribution to the book, “How do you put together a brief against a forest warden who participated in murder in a tiny village buried deep in the marshes of Ukraine?”

Well, you head to the marshes. Gather witnesses. Dig up bodies. These were among the SIU’s singular achievements. In an arresting prologue, Richard Wright, the archaeologist who oversaw the exhumation at Serniki – assisted by his wife and fellow archaeologist, Sonia – recalls how “at two metres down, they found human remains. They called me over and I went down into the hole. What they found was a female skeleton with beautifully braided plaits of hair down to her waist.”

That the excavations took place at all was evidence of the SIU’s deft management of the ever-suspicious Soviet authorities, personified in the enigmatic and formidable figure of the Moscow-based procurator (prosecutor), Madam Natalia Kolesnikov – aka “Madam Kalashnikov”.

Greenwood and his team convinced her to provide formal assistance to the SIU – a level of Soviet co-operation that elided the Nazi-hunting units of other Western countries.

The background of the Cold War meant that the Soviets propagandised about Western perfidy in harbouring the worst Nazi collaborators, while Soviet émigrés abroad in turn accused the SIU and its global counterparts of being communist dupes.

Nonetheless, in another diplomatic coup, the SIU secured permission for Ukrainian witnesses to travel to Australia to give evidence. But that’s where the victories ended. In a standout chapter, Professor Ludmila Stern, an interpreter, explains how the clash of culture and linguistic misunderstandings fatally undermined the witnesses’ courtroom testimonies. Cross-examination made them feel like they were suspects. Where the lawyers sought information about dates or times of day, the witnesses referenced the state of crops or village festivals. Regional dialects sowed more confusion.

“No matter how egregious Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’,” reflects Grant Niemann, who spearheaded the Polyukhovich prosecution, “it might be difficult for an Adelaide jury to relate to something that happened in German-occupied Ukraine nearly 50 years earlier, during the course of a war only remotely connected to them, and in a theatre of war in which Australia played no role.”

By contrast, in the accused the jurors likely saw a fellow Adelaide resident; a “sick old man” who had survived an apparent suicide attempt. Prosecutor Greg James KC suffered blowback from his legal colleagues for even accepting the brief. And the media was hostile.

The jury did not take long to return a verdict of not guilty on both counts.

Co-editor Graham Blewitt, the SIU’s Director for roughly a year before its forced closure in 1992, is an indignant voice throughout. He practically accuses the trial judge of deliberately confusing the evidence of two witnesses during his summing up “to affirm in the jury’s mind how easy it was to make mistakes when it came to identification evidence.”

Karlis Ozols: “Bestial” Latvian SS officer who lived quietly in northern Melbourne (Image: Ashley Gilbertson)

Blewitt takes particular aim at the Keating Government for closing the SIU just as it was rounding on its biggest prey, the “bestial” Latvian SS officer, Ozols – against whom, advised Peter Faris QC, the SIU had a prima facie case of genocide.

Here, Blewitt blames Director of Public Prosecutions Michael Rozenes for not “forcefully” insisting the Attorney-General provide resources to finalise the Ozols investigation. In the “post-Hawke world”, Blewitt writes, Jewish communal leaders such as Isi Leibler found they had “little leverage” in persuading the Government to reverse its decision to prematurely close the SIU. However, the Government did not want to appear the “villain” in the face of the Jews’ fierce campaign.

“What better cover,” Blewitt suggests, “than to make a highly respected Jewish barrister” – Rozenes – “the villain of the piece?”

Authorities using a high-ranking Jew to cloak their indifference to Jewish concerns – now, why does that feel almost paradigmatic?

For all the criticism that the prosecutions failed for coming decades too late, historian Jurgen Matthaus intriguingly argues the contrary: that they came too early. Too early to benefit from the opening of public archives in the post-Soviet Baltic states that helped shift the academic focus of Holocaust historians from the conduct of Nazi chiefs to that of low-level perpetrators who operated the machinery of death. This paved the way for successful prosecutions such as the 2011 conviction of Sobibor camp guard Ivan Demjanjuk in Germany.

And yet, Matthaus writes, “At the turn of the millennium, the Holocaust had not only become a rich field of scholarly endeavour but a contested ground for history wars.”

While Gaza is thankfully not mentioned, it was on my mind throughout. Ground zero for the “history wars” is surely the Holocaust scholars who weaponise the memory of the Shoah against Jews by branding Israel a modern-day Nazi state. Perhaps this is why Nazis in Australia left me with an elegiac sense of loss for the moral clarity of the Hawke era.

Wolf, the sentimental American, asks: “How could Australia say to its Jewish citizens that the murderers of their relatives in World War II by a person now resident in Australia did not matter because the prosecutions would be arduous or because the events had settled into history?”

With the exception of the SIU’s seven edifying years, the answer is: very easily.

JULIE SZEGO is a freelance journalist and author. She writes a Substack newsletter: Szego Unplugged. Her non-fiction book, The Tainted Trial of Farah Jama, was shortlisted for the Victorian and NSW Premier’s Literary Awards for 2015.

Tags: Australia, Holocaust/ War Crimes