Australia/Israel Review

A jihadist goes to the White House

Dec 19, 2025 | Eyal Zisser

Syria’s Ahmed al-Shara’a and Israel

This month marks one year since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the rise of Ahmed al-Shara’a to power in Syria. On November 27, 2024, the ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon came into effect. That same day, the Front for the Liberation of al-Sham, the leading rebel organisation in Syria, led by Ahmed al-Shara’a, then still known as Abu Muhammad al-Julani, launched a surprise attack on Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Within 12 days, the group managed to topple the regime and conquer most of Syria. On Dec. 8, Bashar fled to Moscow, where he was granted political asylum by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

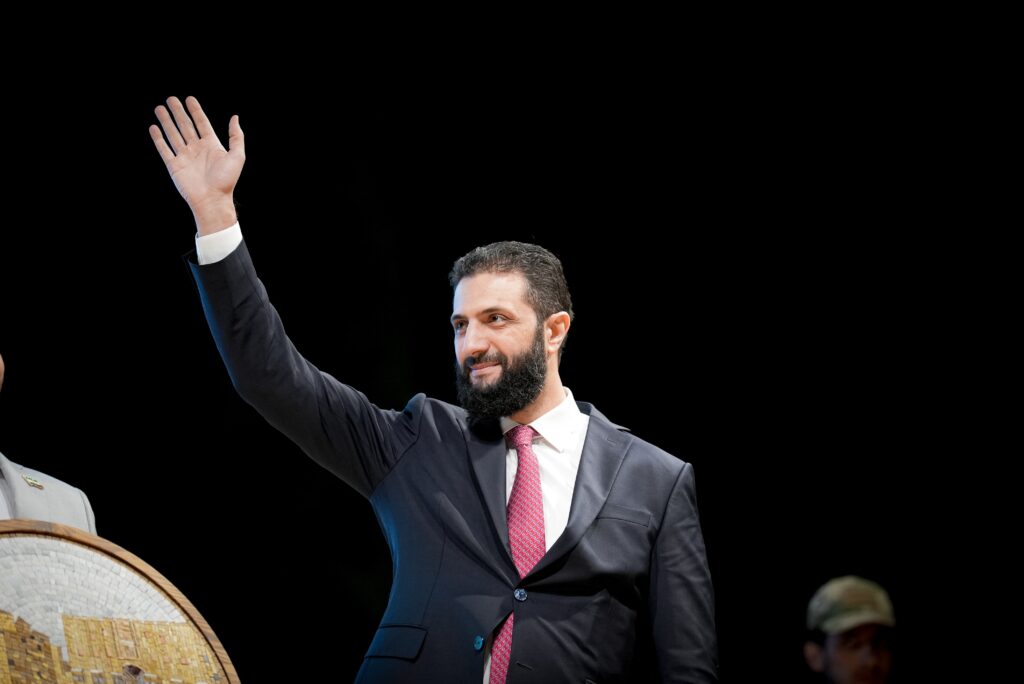

Less than a year later, on Nov. 10, 2025, Shara’a was received with honour at the White House by President Donald Trump. The visit to the White House, which led to the lifting of all economic sanctions imposed by the United States on Syria during the days of Bashar al-Assad, as well as the cancellation of the US$10 million bounty on Shara’a’s head for his past involvement in terrorism, was the culmination of a process of gaining global legitimacy for the new Syrian regime.

Shara’a’s rise to power in Syria last December raised concerns in Israel because the man was a jihadist. According to his own testimony, the outbreak of the Second Intifada in the early 2000s led him to adopt a radical Islamist worldview, to move from Syria to Iraq in early 2003 and join the ranks of al-Qaeda to fight the American forces that occupied that country. When he returned to Syria in 2012 after the outbreak of the civil war, he founded the al-Nusra Front as the Syrian branch of what would shortly become the Islamic State, although in the following years he began to moderate his tone.

He broke away from ISIS and al-Qaeda, and his men, who at one point controlled the Syrian Golan Heights, were careful to keep the border with Israel quiet. At the same time, his rise to power in Damascus was a severe blow to Iran and Hezbollah, who lost an important stronghold and a vital link that connected Teheran to Beirut. For Shara’a, both Iran and Hezbollah were enemies due to the assistance they provided to Bashar al-Assad in his war against the rebels and their involvement in the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Syrians by the Assad regime.

From the moment he came to power, Shara’a sent messages of reassurance to Israel and repeatedly made it clear that Syria, a ruined country without an army, wants to maintain peaceful relations with its neighbours.

For its part, Israel treated him with suspicion, and even before he entered Damascus and took office, it rushed to take control of the border strip between the two countries in order to prevent the possibility of a terrorist attack on its territory. The IDF also attacked and destroyed the former regime’s military equipment, tanks and airplanes to prevent the new regime from gaining control over them.

Israel also attacked Syrian airports that were reported to have been handed over to the Turks, due to Israel’s fear of a Turkish military presence on Syrian soil that would replace the Iranian presence and limit Israel’s freedom of military action there. After all, relations between Israel and Turkey are currently in a severe crisis – although they have not been completely cut off. There is still a dialogue between the two countries mediated by the United States and Azerbaijan, which maintains friendly relations with both Turkey and Israel.

Not long after Shara’a seized power in Damascus, talks began between Israel and Syria, mediated by the United States and the UAE, to try to reach a security agreement that would ensure peace along the border and perhaps constitute a first step towards Syria joining the Abraham Accords. However, every time these talks made progress, events occurred that led to a halt or setback.

For example, in the Spring of 2025, clashes broke out between Shara’a’s forces and the Druze population in the south of the country. The Druze are not Muslims, and as with the Alawites, many Muslims, and certainly the jihadist circles to which Shara’a belonged in the past, consider them infidels. During these clashes, massacres were committed against the Druze civilian population, and Israel, under pressure from Israel’s Druze community, rushed to mobilise on behalf of the Druze in Syria, attacking al-Shara’a’s forces. The American Administration was quick to intervene again.

Needless to say, the current American Administration sees Shara’a as a partner and as the right person to rule Syria. Trump even described him after their first meeting in Saudi Arabia in May 2025 as a “good guy”.

Trump famously had declared during his first term that Syria does not really interest him; that it is only “sand and death”, and its residents are immersed in tribal conflicts with no hope or end in sight; and that he therefore has no intention of interfering in what is happening in that country. But Trump has apparently become convinced that Shara’a is the right person to rule Syria precisely because of his jihadist background. After all, Shara’a is marketing himself to Trump as someone who will bring an end to the bloody war in Syria, fight ISIS terrorism, faithfully serve American interests and even sign an agreement with Israel (although not a peace deal, at least not now). It seems that Trump also listened to Turkish President Erdogan and the Emir of Qatar, whom he described as his good friends, and who, as is well known, have extended their patronage to Shara’a and are seeking to gain influence in Syria through him.

Trump says he sees former jihadist Ahmed al-Shara’a as a “good guy”. (Image: Whitehouse.gov/ Truth Social)

Despite the understandable concern in Israel after the events of October 7, Shara’a does not currently appear to pose a threat, and certainly not an immediate and direct one, since he heads a ruined country lacking any substantive army and continues to see Hezbollah and Iran as hated enemies and the main threat facing his regime. But after October 7, Israel is not willing to take risks. Moreover, domestic political considerations often interfere with Israel’s decision-making, including, in this case, the pressure from the Druze community in Israel on the Government to increase its involvement in what is happening in Syria and even try to establish a safe passage and a corridor to provide aid from Israel to the Druze Mountains region in southern Syria.

Different approaches to what is happening in Syria can be seen within the Israeli security and political system, some of which stem from a fundamental lack of trust in Ahmed al-Shara’a, given the man’s jihadist past. Other approaches stem from a belief that Syria is a lost cause and will never recover, and Israel can exploit Syrian weakness to serve its own interests. For example, there are some Israeli analysts who promote the idea of breaking up the Syrian state into sectarian statelets – Druze, Kurdish, Sunni and Alawite – with the hope that some of these will maintain friendly relations with Israel.

Is it possible to trust Shara’a? The answer is not at all clear. Israel will have to carefully monitor his deeds and actions, not just his statements, and prevent a terrorist entity becoming established in Syria.

In the meantime, the status quo continues along the Israeli-Syrian border, and although the Trump Administration embraces the new regime in Damascus, this will not necessarily lead to a breakthrough in the negotiations between Syria and Israel. It is to be assumed and hoped that through mediation and American pressure, a security arrangement will be reached that will maintain quiet along the border.

However, it seems likely that progress in Israeli-Syrian relations towards actual peace will have to wait until a breakthrough is achieved in Israel’s relations with the wider Arab world. Saudi Arabia will set the tone, when it feels that the Gaza issue is behind us and there is no fear of the renewal of hostilities on Gaza’s border with Israel. After Saudi Arabia, Syria and even Lebanon may join the peace process and the Abraham Accords.

Of course, in the past, the Golan Heights issue was a major obstacle to achieving any Israeli-Syrian peace agreement. Israel captured the Heights from the Syrians during the Six-Day War in June 1967, officially annexing them in December 1981, and in March 2019, US President Trump recognised Israeli sovereignty over the territory. Now, reports are coming out of Damascus that al-Shara’a might be willing to soften Damascus’ traditional stance on this issue. However, as mentioned, any progress will almost certainly have to wait until: 1. a security agreement that will keep the Israeli-Syrian border quiet is signed; and 2. a breakthrough in wider Israeli-Arab relations is achieved in which Syria can also take part.

Prof. Eyal Zisser is the Vice Rector of Tel Aviv University and the holder of the Yona and Dina Ettinger Chair in Contemporary History of the Middle East.

Tags: Israel, Middle East, Syria, United States