Australia/Israel Review

International law experts question the ICC’s case

May 30, 2024 | Jeremy Sharon

The announcement on May 21 by International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Karim Khan that he was seeking arrest warrants against Israel’s Prime Minister and Defence Minister was met with significant pushback from Israel, the United States and beyond.

Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, US President Joe Biden and numerous other figures in Israel and abroad have decried the moral equivalency with leaders of Palestinian terror group Hamas, against whom Khan said he was also seeking arrest warrants in the same announcement.

In addition to the essence of Khan’s allegations themselves, the rapid manner in which the Prosecutor has sought arrest warrants against senior Israeli officials has also been roundly condemned by Israeli politicians across the spectrum.

The pre-trial chamber of the ICC reviewing Khan’s request will now have to evaluate the question of whether the Court has jurisdiction and whether or not the case is admissible based on the fact that Israel has an independent judiciary and is capable of investigating the alleged crimes itself, known as the principle of complementarity.

In terms of the substance of the allegations, however, the pre-trial chamber need only find that there are “reasonable grounds” to believe that the suspect has committed a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court in order to approve the arrest warrants.

But should the charges be confirmed and the warrants issued, would Khan have a convincing case against the two Israeli leaders in the unlikely event that Netanyahu and Defence Minister Yoav Gallant are arrested and the case goes to trial?

The charges

Khan said that Netanyahu and Gallant would be charged with “starvation of civilians as a method of warfare as a war crime,” as well as “extermination and/or murder… including in the context of deaths caused by starvation, as a crime against humanity,” in relation to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

The two would also be charged with “persecution”, with “other inhumane acts” as crimes against humanity, as well as with “willful killing” and “intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population,” as war crimes.

Of the two categories of crimes listed by Khan – crimes against humanity and war crimes – the former is the most severe, being the second most serious crime the ICC can prosecute after genocide.

But the more severe the charges being sought, the higher the burden of proof is on the Court, said Prof. Yuval Shany, a prominent expert on international law at Hebrew University’s Faculty of Law.

The most serious of the charges on Khan’s list, in the context of his allegations that Israel has denied the provisions of adequate humanitarian aid to Gaza, is “extermination and/or murder… including in the context of deaths caused by starvation, as a crime against humanity.”

Crimes against humanity?

Roy Schondoff, a former Israeli Deputy Attorney-General for International Affairs, said that the offence of causing starvation would be hard to prove, and that Khan would need to prove to the Court at trial that the Israeli Government was “intentionally starving people in Gaza, notwithstanding all the difficulties caused by Hamas [in distributing aid], and the far from perfect performance of international organisations.”

The issue of intentionality is key here, since the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding document, states that the crime against humanity of “extermination” requires the “intentional infliction” of conditions of life calculated to bring about the destruction of part of a population.

The crimes against humanity of “persecution” and “other inhumane acts” in the Rome Statute also require a finding of intentionality.

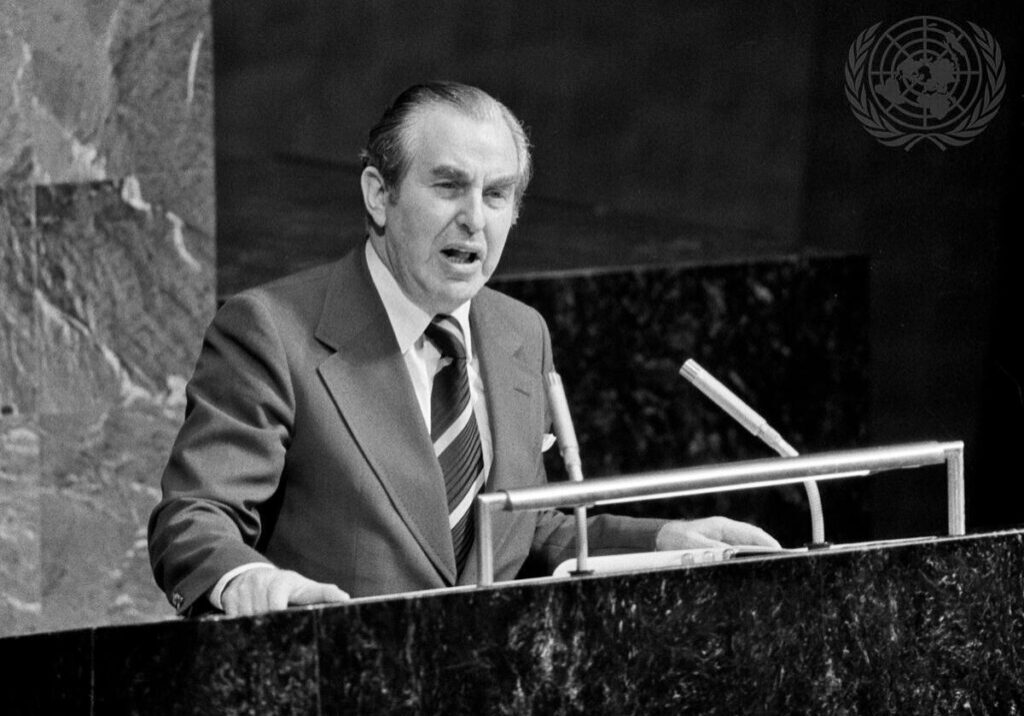

And the charge of starvation of civilians as a method of war also requires a finding of intentionality, said former Canadian justice minister and international law expert Irwin Cotler.

Under the terms of the Rome Statute, intentionality is construed as when the individual “means to cause that consequence or is aware that it will occur in the ordinary course of events.”

“But there is no intention in that regard. It is clear that there has been no policy of starvation; there is no evidence of that,” asserted Cotler.

Shany, of the Hebrew University, also pointed to difficulties with the crimes against humanity charges.

He noted that there have been fluctuations in the degree of control Israel has held over Gaza, the level of humanitarian aid being provided to the territory, and the ability to get that aid to the civilian population.

“The Court would have to show that at the time Israel controlled the area, Netanyahu and Gallant were failing to fulfill their legal obligations, and to show that the policies in place resulted in restrictions to aid at a time when they should have known that this would lead to starvation,” said the professor.

Although he does not believe the pending charges to be “preposterous”, Shany said they do “push the envelope”, adding that he is unaware of any other case where charges of starvation as a weapon of war have been brought by the ICC.

“The factual and legal basis of the case will prove rather difficult,” he said.

In Khan’s announcement on May 21, he referenced controversial comments made by Gallant right at the beginning of the war – on October 9 – that a “complete siege” of Gaza was being imposed and that “no electricity, no food, no fuel” would be allowed into the coastal enclave.

This policy only lasted around two weeks, however, with the first humanitarian aid trucks being allowed into Gaza on October 21, while the piping of potable water from Israel resumed to a limited degree on October 25 but has increased significantly since then.

Shany opined that without such comments by Gallant and others, it would have been much harder to hit Israeli leaders with the charges that Khan is seeking, saying that “when you make outrageous statements, there can be outrageous consequences.”

But he added that these statements were far worse than the eventual policies pursued.

Of note are Israeli claims over several months that there was no limitation on how much aid could be transferred into Gaza.

Despite these claims, after US President Joe Biden warned Netanyahu at the beginning of April that his Administration would pull its support for the war if humanitarian aid was not increased, the Defence Ministry’s Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) unit began announcing dramatically higher numbers of trucks entering Gaza. New crossings were subsequently opened into the territory by Israeli authorities, and the port of Ashdod was opened for the passage of aid as well.

Shany said that the increase in the number of trucks that COGAT said were passing into Gaza was likely due to the easing of restrictions on the hours and days the goods crossings were open, hitherto overly strict inspection policies, and other bureaucratic constraints.

A panel of experts that advised Khan and his team was likely alluding to these restrictions when it referred in a report it submitted to him to “arbitrary restrictions on entry and distribution of essential supplies; cutting off supplies of electricity and water, and severely restricting food, medicine and fuel supplies.”

“Even if you want to be critical of those policies, to say that it is criminal will be a hard threshold to clear for the prosecution,” Shany maintained.

The problems with war crimes

There would also likely be significant difficulties with securing convictions against Netanyahu and Gallant on the war crimes charges of “willful killing” and “intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population,” several experts contended.

Schondoff noted that in order to achieve a conviction on such charges, the prosecutor would need to have knowledge of the information held by the commander responsible for a given attack at the time the attack was carried out.

“It’s not enough that civilians are killed, because that’s the unfortunate reality of armed conflict, unless the scope of civilian casualties is excessive compared to the military necessity,” he said.

“As a prosecutor, that’s hard to determine.”

Schondoff added that the prosecutor would also need to demonstrate that the target hit was not a military objective, meaning there were no Hamas or other terror group combatants or installations at the site. In that context, he noted the wholesale use by Hamas of civilian infrastructure in Gaza for military purposes, something which under international law turns civilian facilities into lawful targets.

“I’ve seen IDF operations for many years and they were never about attacking civilians,” said the former Deputy Attorney-General.

He also noted that there have been very few cases brought by the ICC over the manner in which hostilities have been conducted during a conflict, due to the complexity of proving such allegations.

Crucially, Khan has, on several occasions during the ongoing war, mentioned favourably the rigorous levels of legal scrutiny and accountability within the IDF itself.

“Israel has a professional and well-trained military. They have, I know, military advocate generals and a system that is intended to ensure their compliance with international humanitarian law,” Khan said in October.

But he also insisted that the burden of proving that the protective status of a civilian site had been lost “rests with those who fire the gun, the missile, or the rocket in question,” as laid out in Additional Protocol 1 of the Geneva Convention.

Israel’s legal representatives who addressed the International Court of Justice last week stated explicitly that the Military Advocate General’s office had 55 investigations currently open into incidents of possible criminal misconduct by the IDF during the current conflict, while an independent investigative mechanism was investigating dozens more incidents.

Given that Khan also stated in December that Israel has a “robust system intended to ensure compliance with international humanitarian law,” his decision to request arrest warrants on allegations of war crimes before those investigations have been completed would seem premature and potentially at odds with the principle of complementarity.

“There has been no war in history in which there haven’t been violations of the laws of war,” said Prof. Amichai Cohen, a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, of the allegations against Israel during the campaign against Hamas.

“Are these violations more serious than what has happened in the past? I believe not. We are not worse, and are even better, than others who have waged war.”

Jeremy Sharon is the Times of Israel’s legal affairs and settlements reporter. © Times of Israel (timesofisrael.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Gaza, Hamas, International Criminal Court, Israel