Australia/Israel Review

Saudi Arabia’s problematic nuclear “asks”

Aug 29, 2023 | David Schenker, Simon Henderson

According to accounts of recent off-the-record comments by Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (aka MbS), the kingdom wants three main things in return for a potential normalisation agreement with Israel: US security guarantees, access to top-shelf American military equipment and technology, and support for a domestic civil nuclear program. The third “ask” may be the most challenging for Washington, since it includes access to uranium enrichment technology that can be used to produce a nuclear explosive.

Saudi weaponisation assurances?

The most recent iteration of such a deal would create a “Nuclear Aramco”, mimicking the historical involvement of US oil companies in the 1930s that eventually led to the Saudis wholly owning the world’s largest oil company. Riyadh reportedly suggested this idea to US officials in part to reduce their concerns about potential weaponisation.

Yet Washington also surely recalls the Crown Prince’s nuclear remarks in a 2018 interview with the US version of “60 Minutes”: “Saudi Arabia does not want to acquire any nuclear bomb, but without a doubt if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible.” Some might dismiss this as an impromptu comment rather than a statement of policy, but the interview was pre-recorded and came amid an important trip to Washington – his first after being named heir to the throne. Moreover, his uncle, the late King Abdullah, gave the same message to US special envoy Dennis Ross in 2009. And as recently as last December, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan told a conference in Dubai, “If Iran gets an operational nuclear weapon, all bets are off.”

What exactly does Riyadh want?

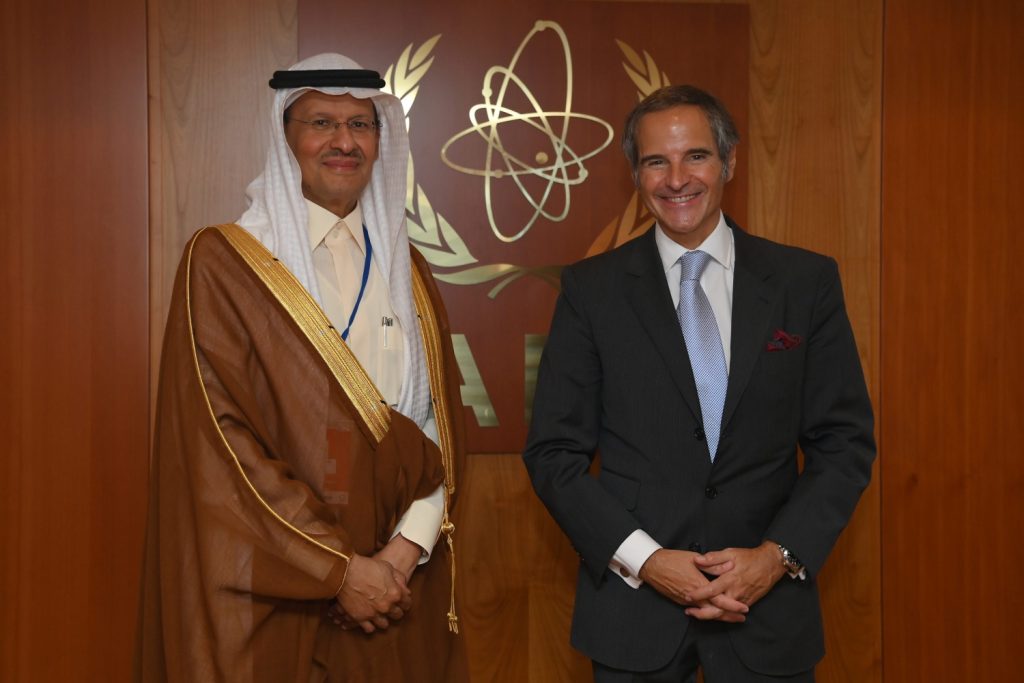

Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, the Crown Prince’s half-brother, gave an indication of the kingdom’s specific thinking this January, telling a local mining conference that Riyadh wants “the entire nuclear fuel cycle, which involves the production of yellowcake, low-enriched uranium, and the manufacturing of nuclear fuel both for our national use and of course for export.” The potentially troublesome phrase “entire nuclear fuel cycle” implies that the kingdom wants to reprocess spent fuel, which can generate explosive plutonium as a side product.

In the end, MbS is highly unlikely to accept any agreement that gives the kingdom less than what Washington conceded to Iran in the 2015 nuclear accord. Indeed, US-Saudi discussions on the matter have centred on Iran’s regional policies and its huge enrichment program, which is supposedly intended to fuel civil reactors but has also been clearly identified as a military program. Most observers believe Teheran is now on the cusp of being a nuclear-armed state – if it so chose, it could quickly enrich its large stockpile of fissile material to produce as many as five nuclear bombs, though it may need months or even years to perfect the requisite implosion mechanism, missile warhead, or other delivery system.

Saudi Arabia’s current nuclear plans include the proposed construction of two civil power reactors, pruned back from the 16 reactors proposed in 2013. According to Riyadh’s logic, using its recently discovered indigenous uranium deposits to fuel new reactors and generate electricity would enable it to export most of its oil, which remains the cheapest in the world to produce and is still necessary to fund the kingdom’s transition to a greener, more diversified economy in the coming decades. Yet the size and quality of its uranium reserves are questionable. In April, Bloomberg reported that Saudi “exploration yielded only ‘severely uneconomic’ deposits so far.”

Moreover, US officials have already expressed concerns about the kingdom’s previously reported steps toward nuclearisation. On August 4, 2020, the Wall Street Journal cited unnamed officials who asserted that China had built a facility in the Saudi desert to convert uranium ore into yellowcake, an intermediate stage before enrichment. The next day, the New York Times also cited unnamed sources in reporting that two buildings near Riyadh could be undeclared “nuclear facilities”.

If the kingdom has already built enrichment facilities, where did it acquire the necessary technology? Well-placed Western officials concede that Saudi Arabia was the fourth, unpublicised customer of A.Q. Khan, the late Pakistani nuclear scientist and proliferator who sold centrifuge equipment to Iran, Libya, and North Korea. Khan retired in 2001, suggesting that his activities with the kingdom happened more than 20 years ago.

US options

Given that the situation with Iran provides the overall context for US-Saudi nuclear deliberations, any technical advance by Teheran could change everything overnight. If the status quo persists, however, the current ambiguity surrounding the scope of Iran’s capabilities and potential US deal-making could provide opportunities for diplomacy with Riyadh.

Grandfathering in existing Saudi facilities may be one way forward. Prince Abdulaziz stated in January that “the kingdom intends to utilise its national uranium resources, including in joint ventures with willing partners in accordance with international commitments and transparency standards.” Although this seems to run against the idea of the US directly monitoring Saudi activities as part of a “Nuclear Aramco”, it does imply an unspecified role for the Vienna-based IAEA, the world’s top nuclear watchdog. Currently, the kingdom has a low-level agreement with the IAEA but has not signed the “Additional Protocol”, which allows for intrusive inspections. One way to boost US confidence in a “Nuclear Aramco” scenario would be for Riyadh to submit to more rigorous and continuous IAEA inspections, as more than 140 countries have done.

Another consideration is Israel, whose Government has not yet articulated an authoritative, unified view on a potential Saudi nuclear power program. In June, Energy Minister Israel Katz voiced opposition to such a program at the United Nations. During an interview a few months later, however, National Security Advisor Tzachi Hanegbi downplayed the potential risks. Notably, Israel opposed Jordan’s proposal to build a nuclear energy plant in 2009 due to safety concerns. A reactor on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coast – distant from Iran but in range of missile fire from Teheran’s Houthi partners in Yemen – would no doubt generate similar fears.

Saudi enrichment demands place the Biden Administration in a difficult position as well. Washington has long proscribed enrichment when negotiating civil nuclear cooperation with regional states. For instance, it convinced the United Arab Emirates to abjure the practice and opposed Jordanian ambitions to pursue commercial enrichment. Indeed, the US legal framework for civil nuclear cooperation – Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, under which Washington has signed agreements with 23 countries – explicitly prohibits enrichment and reprocessing.

Yet there have been exceptions, most notably India. And earlier this year, the US included enrichment in the civil nuclear agreement it signed with Britain, Canada, France, and Japan, in a deal intended to insulate allies from sanctions against Russia, the world’s leading provider of civil nuclear fuel. The game-changing regional possibilities of Israeli-Saudi peace – coupled with concerns that Riyadh might look elsewhere for its nuclear program if Washington does not help, which would mean fewer safeguards – could push the Biden Administration toward a more flexible outlook on enrichment.

Even as it encourages normalisation between Riyadh and Jerusalem, Washington is probably trying to balance policies that constrain Iran, preserve US diplomatic options, and address Middle East proliferation concerns – namely, the likelihood that further Iranian nuclear advances will prompt other regional countries to actively pursue their own military nuclear alternatives. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the UAE are widely believed to have the technological base for such efforts or access to it, while Russia, China, and perhaps even France may oblige with additional help (e.g., Paris signed a nuclear cooperation agreement with Riyadh in July).

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. David Schenker is the Institute’s Taube Senior Fellow and director of its Rubin Program on Arab Politics. © Washington Institute (washingtoninstitute.org), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel, Saudi Arabia, United States, nuclear

RELATED ARTICLES

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio