Australia/Israel Review

Iran’s Iraq plans revealed

Nov 29, 2019 | Seth J. Frantzman

US policy has been a mix of guns and butter in Iraq since the invasion of 2003: offering military training and arms and trying to butter up some officials that Washington thought would be its champions in Baghdad. But at every turn an Iranian octopus was lurking, outplaying the ham-fisted American attempts to exert influence in Baghdad, even manoeuvring Iranian-backed candidates into office with US backing, tricking Washington to make the US think it had “won.”

A trove of documents obtained by The Intercept and shared with the New York Times reveals how Iran outmanoeuvred the US.

Although much of this was known, the 700 pages of documents, translated from Farsi, show new details and, the report notes, shows how Iran got a firm grip on Iraq and is using it as a “gateway for Iranian power” that now stretches through Syria to Lebanon and increasingly threatens Israel. Iraq is the “near abroad” for Iran now, and Iran is building its own IRGC in Iraq, called the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU).

The archive of documents comes from 2014-2015 and is from “officers of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security.” 2014-2015 was a pivotal year because it is when ISIS swallowed up a third of Iraq and threatened Baghdad. In response, Iran sent advisors, and Iraq’s Ayatollah Ali Sistani called for mass mobilisation of Shi’ite men to fight. That became the PMU, which became part of the Iraqi Security Forces; now their party is the second largest in Iraq.

2015 was also the year of the Iran deal when Washington and Teheran appeared on the same page in Iraq. The US under the Obama Administration supported the Iranian-backed Shi’ite sectarian Nouri al-Maliki to be prime minister and then supported his replacement Haider al-Abadi. In both cases, Washington wanted a “strong man” in Baghdad. And they got one. But so did Iran.

Iran didn’t have an uphill battle in Iraq, the documents show. Many leading Shi’ite Iraqis had aided Iran in the 1980s against the brutal Saddam Hussein regime. While Donald Rumsfeld was shaking hands with Saddam, men like Hadi al-Amiri were with the IRGC.

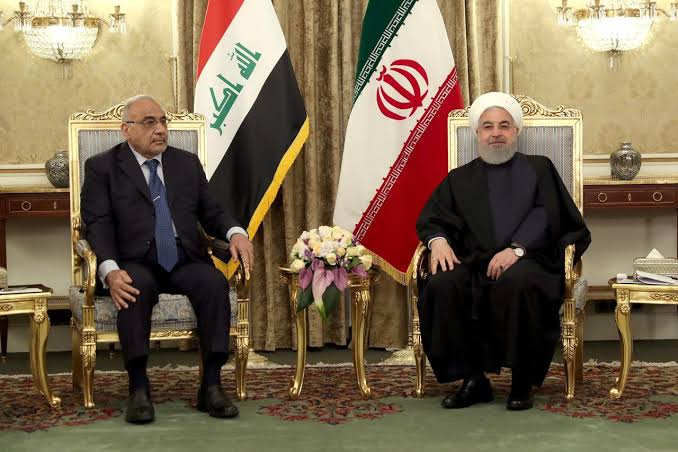

Even current Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi had a “special relationship” with Iran, the documents note. In each case that means Teheran had an open door to most ministries, including key areas like the Interior Ministry and oil sector.

What were Iran’s goals? It wanted Iraq not to sink into chaos, as eventually happened in 2014. It wanted to stop an “independent Kurdistan,” which it did in 2017. It wanted to protect Shi’ites. It wanted to crush Sunni takfiri (apostates), and jihadists, like ISIS. It has done that.

Win, win, win, and another win for Iran.

Unsurprisingly, Teheran benefited not because it is some genius actor in Iraq but because it had a massive pool of recruits and sympathisers, and people that needed its largesse. When ISIS came knocking in 2014, it’s no surprise that Qasem Soleimani, head of the IRGC’s Quds Force, was looked on as a saviour by some in the Shi’ite sectarian militias.

Iran also benefited from how the US tends to treat its friends in the Middle East. Because the US, through men like James Jeffrey at the State Department, view relationships with people in Iraq and Syria as “temporary, transactional and tactical,” the US doesn’t cultivate long-term friends. It uses locals and then discards them, thinking that this short-term planning will work. Iran played the long game, the one where you start in 1981 and you work your way to get to 2019. “The CIA had tossed many of its longtime secret agents out on the street, leaving them jobless,” The Intercept notes.

To track American efforts, the Iranians not only infiltrated Sunni Arab parties and offices in Baghdad, they also followed US movements. They were concerned that Washington would work with Sunnis as it had in the past.

The real coup for Iran was penetration of government institutions at all levels. In one discussion, in late 2014 or early 2015, the Iranians went down a list of Iraqi officials. At the Minister of Municipalities they didn’t need to worry: These were members of the Badr Organisation, linked to the PMU and also to Amiri, allies of Iran. The Minister of Transport was close to Iran. PM Abdul-Mahdi was close to Iran. The Foreign Minister was close to Iran. The Minister of Health is from Maliki’s Dawa Party. He’s “loyal,” the note said. They were concerned about men close to Sadr, who now runs the largest party in Iraq. They preferred others.

Iran had larger strategic considerations as well. It needed Iraqi airspace to supply the Syrian regime and also to get weapons to Hezbollah. Soleimani was sent to deal with the problem through the Ministry of Transport. It wasn’t even a discussion; the Minister put a hand over his eyes to indicate that he would pretend not to see the flights. Soleimani kissed the man’s forehead.

But Iran may have overstretched and been too arrogant. In 2015, an agent described the Sunnis in Iraq as “vagrants” and mocked their cities for having been destroyed by ISIS. They had little future.

The Iranians would also outplay the Kurds in 2017 and use the Americans to help punish the Kurdish region. By 2018 they were supremely confident, but protests against Iran and its allied militias were beginning. Now those protests have grown. Soleimani went to Baghdad in October to help suppress them. Around 350 Iraqis have been gunned down by snipers, many allegedly backed by Iran. But it could backfire.

Indeed, agents reported back to Iran that Soleimani’s star was fading. He was posting too much on social media. Iraqis, angry at Shi’ite militia abuses were saying they would turn to America and “even Israel” to enter Iraq and save it from Iran. There, the seeds were sown in 2015 for the mass protests that have come in 2019.

Iraq’s future is still unclear. But what is clear is that Iran sought total domination of Iraq. It grew arrogant through the open channels of support it had, often due to the legacy of the 1980s war. But a new generation was rising and they only knew Iran as the power in charge: not the liberator, not the underdog.

Iran now has to control Iraq. And Iraq is not easy to control.

Seth J. Frantzman is opinion editor and Middle East affairs analyst at The Jerusalem Post. © Jerusalem Post (www.jpost.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iran, Iraq, United States