Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Bridging the Gulf

Sep 1, 2019 | Sarah Jacobs

Altered strategic realities offer new opportunities in the GCC

In February 2019, diplomatic history was made as leaders from the Arab Gulf States joined Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu in attending the US-led talks in Warsaw to discuss shared concern over Iran.

Then, in June, they assembled again, this time at the “Peace to Prosperity” conference in Bahrain where the US unveiled its economic plan for the Palestinian people.

These collaborative meetings are indicative of the great transformations occurring in the strategic political landscape of the Gulf. They call attention to the changing reality that nations are putting aside their differences to work in tandem with past enemies towards greater security of the region in the face of a new threat.

States that once were viewed as existential enemies are now potential partners for peace. As one of the most critical economic and geopolitical locations in the world, the Gulf States have stepped up to play a pivotal role in combatting Iranian hostility.

Furthermore, the escalating threat from Iran has created opportunities for Western nations like Australia to nurture existing relationships in the region. These partnerships can in turn help to safeguard economic, diplomatic, and physical security in the Middle East and around the world.

Oil Gateway to the World Under Threat

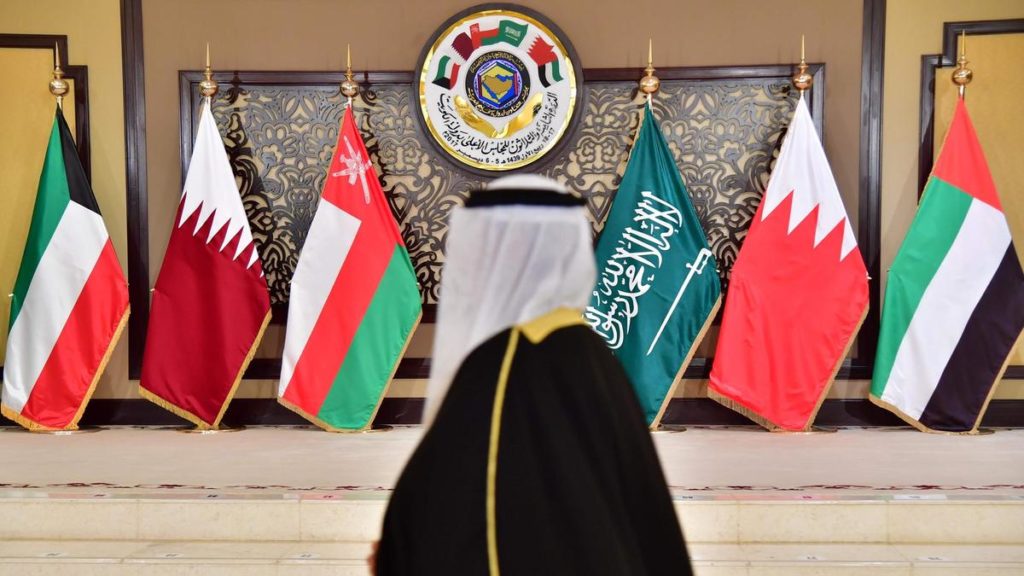

The six states belonging to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are situated in the not-so-friendly neighbourhood of the Arabian Peninsula. GCC member states Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are all Arab monarchies with economies rooted in oil and natural gas exports.

The six GCC member states produce one-sixth of the world’s crude oil supply and one-third of the world’s liquified natural gas. They export some 21 million barrels of oil per day through the Strait of Hormuz, the “world’s most important oil chokepoint,” according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

According to The Economist, shipping companies have already seen a 10% increase in insurance costs for tankers that pass through the Strait, thanks to Iran’s antagonistic activity in international waters over the past few months. This is a huge concern for the Gulf states that rely on the maritime passage for almost all of their import and export needs.

Australia has accepted US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s request to join US-led efforts to defend maritime security in the vital Strait of Hormuz.

This follows three precarious months during which six tankers were sabotaged with explosives, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps members boarded and seized three tankers, including one large British one, and an American drone was shot down in the Gulf. Iran has been blamed for all of these attacks, most in international waters.

The UK has already allocated two warships from the Royal Navy to escort their shipping vessels through the Strait of Hormuz.

Additionally, South Korea and Poland have heeded the US call for a coalition for maritime security as a preventative measure against further Iranian aggression.

On July 22, then-UK foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt declared Iran’s obstruction against the UK vessel an “act of state piracy” and a violation of international water rights. Hunt warned, “If Iran continues on this dangerous path, they must accept a larger western military presence in the waters along their coastline.”

While the GCC member states are continuing business as usual (for now), it is clear from the swift responses of major world powers that belligerence affecting the Strait is taken extremely seriously. Security in the Strait of Hormuz is particularly crucial for Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar, which have no other path out to the Arabian sea, other than through this narrow passage.

In the words of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Gulf-expert Anthony H. Cordesman, a crisis that endangers or blocks the petroleum and gas exports through the Strait of Hormuz “would almost certainly require a near-total maritime crisis or escalation… that goes far beyond attacks on tankers and shipping.”

Internal Alignments in the GCC

Cooperation amongst GCC members is not a given, with different states pursuing their own particular interests. Rifts have developed mainly along sectarian lines, with some nations backing Shi’ite Iran and others backing Sunni Saudi Arabia.

The most significant rift within the GCC has been the excommunication of Qatar by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt (which is not a GCC member, but is a major player in Middle Eastern politics). In June of 2017, these states officially severed ties with Qatar due to its alleged continued support of terrorist militias that feed sectarian conflict in the region.

The Saudi-led boycott of Qatar has continued to the present day, and it is expected that pressure will persist until Qatar stops funding adversaries of Saudi Arabia and the US, allegedly including extremist groups Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood, Hezbollah, and al-Qaeda. Of course, many of these terrorist groups receive ample funding and support from Iran as well, which continues to call for the destruction of Israel and “death to America” regularly.

By choosing to isolate one of their own to punish it for allegedly playing on Iran’s team, it is clear that the vast majority of the GCC has strongly aligned itself against Iran. The Gulf states are well aware of Iran’s expansionist ambitions and aspirations to dominate the oil market, achieve military nuclear capabilities, and back subversive Shi’ite groups that threaten to infiltrate majority Sunni nations.

The impact of Iranian-supported terrorism and destabilisation has been felt in all of the Gulf States, perhaps with the exception of Qatar, and all GCC members have enacted anti-terrorism legislation, joined international coalitions to defeat groups like ISIS, and have appeared to be taking actions to prevent extremism in their respective countries.

In April, Bahraini authorities arrested and imprisoned 139 members of a Shi’ite militant group allegedly attempting to build a “Bahraini Hezbollah.” Bahrain condemned these members for training with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and smuggling Iranian weapons into Bahrain.

In July, Kuwait deported members of a Muslim Brotherhood terror cell that had fled to the Gulf from Egypt. In recent years, Kuwait has also arrested members of Hezbollah that formed a terrorist cell supported by Iran and Lebanon. Kuwait’s crackdown on terrorist groups has kept the country safe from attacks since 2015, when an ISIS suicide bomber took 27 lives at a mosque.

Oman has also impressively avoided terrorist attacks, in part by remaining dedicated to stability domestically and impartiality in foreign policy, especially by choosing neutrality in the Iran-Saudi proxy conflict in Yemen on its southern border.

For the Saudis, counterterrorism efforts focus heavily on opposing extremist groups funded by their long-standing adversary Iran. Meanwhile, the Saudis have been fighting what amounts to a proxy-war against Iran in Yemen, which has created one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world today – 3.3 million Yemenis are displaced while 16 million struggle with hunger and malnutrition, according to the United Nations.

Iran funds and provides weapons and support for the Houthi rebels, the Shiite Yemeni militia that threatens Saudi Arabia’s southern border. Earlier this year, the Houthis claimed responsibility for striking a Saudi oil pipeline and have killed at least one person with rocket fire aimed at an airport in the southern city of Abha. In total, an estimated 225 ballistic missiles have been fired towards Saudi Arabia by the Houthi militia.

The UAE, in an effort to distance itself from the four-year-long war in Yemen, recently pulled most of their troops out of the Saudi-led coalition. Houthi missiles have also targeted the UAE, so they may be interested in lowering tensions to avoid the possibility of future attacks.

Of course, Saudi Arabia previously had a long record of promoting and exporting extremist Islam and Islamism internationally. Even today there are serious concerns about respect for human rights by these countries in the counter-terror efforts, encompassing both Saudi and Bahraini treatment of their Shi’ite populations, and the behaviour of Saudi and UAE armed forces in fighting pro-Iranian jihadist groups in Yemen.

Changing Relationships with Israel

In addition to uniting against Iran and fighting terrorism, the second substantial transformation of the Gulf states is their improving relationships with the State of Israel.

Slowly but significantly, Gulf states that had never recognised Israel are taking steps towards normalisation with the Jewish state.

Concern over Iran has been the primary catalyst for the realignment of relations between Israel and the Gulf States. Both Israel and most GCC members stand opposed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement with Iran and condemn Iran’s breaking of the deal in order to advance its nuclear program. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has called Iran’s Supreme Leader “the Hitler of the Middle East,” due to his agenda of “trying to conquer the world.” Both Israel and the GCC members (excluding Qatar) agree that nuclear weapons attached to Iran’s ideology would be an existential threat, especially to the Middle Eastern states in Iran’s backyard.

A once-unthinkable sight: Israeli Culture Minister Miri Regev enjoying friendly hospitality in Abu Dhabi

The pressing issue of Iran and its sponsorship of terrorism in the region is also one of prime concern for Israel and its neighbours in the Gulf, allowing for the Arab states to see Israel as a source of stability, counterterrorism techniques, and intelligence services in the region.

Although none of the six GCC nations have established diplomatic relations with Israel, there have been many high-profile meetings between GCC members and Israeli politicians, businessmen, and journalists for the first time in recent years.

Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu visited Oman’s capital last year, and Mossad head Yossi Cohen claimed in July that Muscat would establish formal relations with Jerusalem (though Oman’s foreign ministry quickly denied their readiness to go this far).

Israeli Culture Minister Miri Regev visited Abu Dhabi last year as Israeli Judo athletes competed and won gold at a tournament in the UAE. The Israeli national anthem Hatikvah was publicly played – something which has rarely been the case at sporting competitions in the Arab world.

Israeli Foreign Minister Yisrael Katz attended a UN conference in the UAE in July where he talked openly with the Gulf nations about technology, transportation, and environmental issues. Katz emphasised the Israeli Government’s work “to promote the normalisation policy” with the Arab Gulf states.

In February, a group of Kuwaiti businessmen toured various historical and religious sites in Israel, and journalists from Saudi Arabia toured Israel in July. The Israelis and Saudis revealed they have held secret talks about Iran beginning as early as 2014, and some Israeli and Saudi companies now have business partnerships, especially in the technology and cybersecurity fields. An Israeli company reportedly sold sophisticated spy systems to Saudi Arabia, making it perhaps the first Arab country to use Israeli security-technology. The Kingdom has also sought access to Israel’s Iron Dome missile defence system for protection against Houthi attacks.

In an interview with The Atlantic, Saudi Crown Prince Salman acknowledged the right of the Jewish people to live in “their own land,” and recognised the economic benefits of partnering with Israel. In his words, “if there is peace, there would be a lot of interest between Israel and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries.”

After the “Peace to Prosperity” workshop, Bahraini Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed Al-Khalifa told The Times of Israel, “We do believe that Israel is a country to stay, and we want better relations with it, and we want peace with it.” The interview essentially amounted to the Bahraini minister acknowledging Israel’s right to exist, a first for any Arab state besides Egypt and Jordan.

On the Palestinians

The US-sponsored “Peace to Prosperity” conference in Bahrain focused on the future of Palestinian economic development, with the US offering a US$50 billion investment plan designed to transform Palestinian infrastructure and promote unprecedented economic growth. But Palestinian leaders decided to boycott the event, apparently choosing continued hardship over better lives for their people simply to avoid any collaboration or normalisation with their “enemies,” the US and Israel.

Thirteen Palestinian businessmen from Hebron, known as the Palestinian Business Network, attended the conference despite the Palestinian Authority (PA) opposition, threats, a naming and shaming social media campaign, and being labelled as traitors.

The Bahrain conference allowed the world to see how the Palestinian leadership continues to isolate itself. Even after the PA and Hamas implored their fellow Arab states to join their boycott of the conference, the Gulf nations seemed to have no problem hosting and attending an economic conference with Israeli business representatives.

While some Palestinians (and Arabs in the Gulf States) feel ready to accept normalised business relations with Israel, others feel betrayed by the Gulf’s growing ties with the Jewish state. In Baghdad, protestors gathered at the Bahraini embassy to express their distaste for the Gulf state hosting and participating in talks with Israel. The demonstrators replaced the Bahraini flag with a Palestinian one.

In addition to the economic plan outlined in Bahrain, the PA also rejects humanitarian projects for Gaza, such as the recently-announced plans for the building of a new hospital sponsored by Qatar, because Hamas, whom they regard as enemies, did not consult with them before partnering with Israel and Qatar on the project.

Following the conference, Oman announced it would open an embassy in the Palestinian West Bank, a first for any Gulf state. Analysts believe this move was designed to appease the Palestinians after welcoming Netanyahu and beginning talks to normalise relations with Israel. Yet Palestinian leadership rejected Oman’s attempt at balance, with PLO Executive Committee member Hanan Ashrawi declaring, “If opening the embassy is even remotely related to recognising Israel, we will totally refuse it.”

As the Palestinian Authority stages protests, promotes social media intimidation campaigns, and threatens the safety of businessmen who dare to represent their interests at a conference designed for them, it becomes clear that these self-isolating tactics do not correspond with the Gulf states’ interests in a diplomatic solution, and declining willingness to make the Palestinian cause a centrepiece of their foreign policy, given other more urgent priorities.

Australia’s Position

Finally, Australian policymakers need to be aware of the strategic changes in the Gulf region, and how Australia’s national interest can be advanced by supporting our allies in the Middle East, and recognising that the new alignments in the region create new opportunities.

Canberra policymakers have sometimes viewed Middle East relationships as a choice between Israel and the Arab states. But legislators need to update their view: Australia can today unquestionably have it both ways.

While Australia enjoys a strong relationship with Israel, trade and military involvement in the region has led to significant strategic ties with the Gulf States as well. For the past 29 years, Australia has also maintained a long-term commitment to Middle East maritime safety through the Royal Australian Navy’s Operation Manitou.

Australian forces helped free Kuwait from seven months of occupation by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime in 1990. Kuwait has not forgotten Australia’s participatory role in their freedom, and this trust has paved the way for substantial investment, trade, and academic connections.

Just this past June, the Kuwait Foreign Petroleum Exploration Company, or Kufpec, announced it would raise its output of oil and natural gas with three new exploration sites off the coast of Western Australia. As OPEC’s third largest producer of oil, Kufpec’s significant investments in Australia contributes to Kuwait’s $8.7 billion investment in Australia (2017).

The UAE is Australia’s largest trading partner in the Middle East. Last year, Australia exported close to A$4 billion in merchandise to the Emirates.

The convenience of travel agreements with airlines Emirates and Etihad allows the 23,000 Australians living or working in the UAE a selection of over 150 direct flights per week. Australia also operates a strategically important defence hub out of the UAE called Al-Minhad.

All of the GCC countries are keenly aware of the eventuality of dwindling oil reserves, and Australia has the opportunity to play a key role in their attempts to diversify their economies. The Gulf states are actively pursuing foreign investments, as well as educational and employment opportunities for their extremely youthful populations. Australia should continue to build upon its already substantial trade agreements and people-to-people connections for mutually beneficial prosperity with the Gulf.

As far as physical security of energy transportation, Australia need only observe the actions of her allies for examples of immediate preventative steps.

Following the standard set by the US, UK and South Korea, Australia will now be supporting a rules-based liberal order and freedom of navigation in the strategic Strait of Hormuz by participating in the US-led maritime coalition. Australia’s national interests clearly include protecting global oil supply from Iranian aggression in the Persian Gulf that would seriously impact the price of oil shipments.

Australia could also join her allies in pressuring Iran to come back to the negotiating table on an improved nuclear deal. In December 2018, Prime Minister Scott Morrison indicated that his Government would consider additional autonomous sanctions on Iran. While Foreign Minister Marise Payne has encouraged Iran to cease breaching the condition of the JCPOA, Morrison has not yet increased sanctions. Economic sanctions would add to the pressure on Iran to end its rogue behaviour, and thus safeguard not only Australia’s role in the global oil economy, but also the Gulf states’ reliance on safe trade.

The door is open to a bright future between GCC members and Australia. The Gulf States feel acutely the danger of growing Iranian hegemony if left unchecked, and their geographical and economic vulnerability, as 20% of the world’s oil supply passes through the Strait of Hormuz. Meanwhile, Australian trade with Iran is insignificant.

GCC states seem much more likely to build partnerships for economic development with states who have demonstrated a willingness to help contribute to these security needs.

In its own national interests, Australia should continue to focus on increasing its positive collaboration with the GCC on counterterrorism, regional security and economic growth, just as the Gulf States have begun to explore increasing collaboration with Israel. Australia has taken a necessary first step by participating in maritime efforts to contain the threat that preoccupies GCC members and has brought them closer to Israel – the rogue behaviour and expansion plans emanating from the Iranian regime.

Tags: Gulf states, Iran, Israel, Middle East