Australia/Israel Review

Israel’s election – a backgrounder

Feb 3, 2019 | BICOM

On December 24, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu announced that new elections would take place on April 9. This briefing examines how Israeli elections work, the reasons for the early elections; and analyses recent polling data.

HOW DO ISRAELI ELECTIONS WORK?

Israel has a directly proportional, party list voting system, in which each voter chooses one party, and the country elects 120 members to the Knesset, Israel’s unicameral parliament. The threshold for a party entering the Knesset is 3.25% of votes cast (raised prior to the 2015 election, and equivalent to around four seats or 150,000 votes in the last election), and if a party fails to pass the threshold its votes are discounted. Parties have until Feb. 21 to submit their lists of candidates, with Likud and Labor among those selecting through competitive primaries. Though voter turnout has seen a downward trend in the last two decades, in 2015 it increased to 72%.

A week after the April election, following consultations with party leaders, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin will ask the party leader in the best position to form a coalition to try and do so. This is usually the leader of the largest party but not necessarily so (for example if a group of smaller parties, together representing a Knesset majority of 61 or more, refuse to serve in a Netanyahu-led government, then the leader of a smaller party could form a government). No party has ever achieved an overall majority, and coalitions typically consist of at least four parties.

WHY WERE ELECTIONS CALLED?

The current Government has been in power since May 2015 and consists of Netanyahu’s Likud (30 Knesset seats), the Religious-Nationalist Jewish Home party (eight seats), the ultra-Orthodox Shas (7 seats) and United Torah Judaism parties (UTJ) (six seats), the socio-economic focused centrist Kulanu party (ten seats), and until a few weeks ago, the hawkish Yisrael Beiteinu party (six seats). The Knesset opposition had been led by the Zionist Union, comprising Labor and Hatnua parties (24 seats), the centrist Yesh Atid (11 seats), the left-liberal Meretz party (five seats), and the Joint Arab List (13 seats).

The catalyst for early elections was the difficulty in getting ultra-Orthodox parties to agree on a new law for conscription of ultra-Orthodox Jews, but this is widely interpreted as a pretext.

The timing was driven by Prime Minister Netanyahu’s priority to hold elections before Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit decides whether or not the Prime Minister should be indicted over allegations of bribery, fraud and breach of trust. The police have recommended an indictment in three cases against Netanyahu and it is widely reported that Mandelblit hopes to make his announcement in February or early March.

Early elections in April came as no surprise. By law, elections were due no later than November 2019 and coalition partners usually fall out long before the Government’s term is due to end. At three years and 11 months, the 20th Knesset (parliament) of Israel has lasted longer than most.

HOW IS THE ELECTION SHAPING UP?

Israeli polls usually fail to accurately predict the election outcome, because of the complexity of the party system, and large numbers of undecided voters who make up their mind at the last minute.

Israel’s directly proportionate, party list electoral system enables the party system to reinvent itself for every election, and the announcement of elections has triggered a fast-moving process of parties forming, merging, splitting, and recruiting new high-profile candidates.

The election campaign has only just begun but our aggregate analysis of seven polls published between Jan. 2 and 8 suggest some early insights:

• Likud maintains an overwhelming lead. Polls suggest it will win almost 30 seats, as it has for much of the last 10 years, despite the expectation that the Attorney General will recommend that Netanyahu be indicted. Likud’s strength reflects a loyal support base, bolstered by less ideological voters who see Netanyahu as a safe pair of hands. The large gap between Likud and all other parties, is the basis of a wide consensus among Israeli commentators that Netanyahu will likely lead the next government.

• The right-wing bloc – Likud, Jewish Home, the New Right (Hayemin Hachadash, a new party that split from the Jewish Home), and Yisrael Beiteinu – are expected, according to latest polls, to win a similar number of seats to the 2015 election. The parties in the current Government coalition (the right-wing parties plus Shas, UTJ and Kulanu), who Netanyahu has said would form his future government, are expected to win a majority of 61 seats, suggesting Netanyahu would be able to form the next coalition. This could change if the Attorney-General recommends Netanyahu be indicted for bribery before the elections and one or more of these parties refuse to serve with him in government as a result.

• The split within the Jewish Home party has increased the chance that a right-wing party fails to win 3.25% of the vote, depriving a future Netanyahu coalition of crucial seats. In late December, the Jewish Home’s most popular ministers, Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked, announced they were forming a new party, the New Right. This reflects their long-held ambition to win over more secular, middle-class Jewish-Israeli voters – a mission hampered by Jewish Home’s affiliation with the national-religious sector and the influence of settler rabbis. Bennett and Shaked are now able to form their own list of secular and religious candidates. But the move has weakened Jewish Home and other smaller right-wing parties, with some polls placing Jewish Home, Yisrael Beiteinu and ultra-Orthodox party Shas below the electoral threshold of 3.25%.

• The centre and left are highly fractured with several parties built around individual personalities rather than specific policies and are currently unable to mount a challenge to Netanyahu. Three rivals – the newly announced Hosen Leyisrael (“Resilience for Israel”) party of former IDF Chief of Staff Benny Gantz, Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid, and Labor led by Avi Gabbay – are each expected to win between 9 and 15 seats, with Gantz looking strongest, followed by Lapid. Each party leader considers himself a prime ministerial candidate, and at this stage is unwilling to give up their top spot in any potential merger.

• New entrant Gantz is significant because of the strength of his polling numbers. Despite having announced no policy platform or candidate list and having said almost nothing to the media, Gantz is currently expected to win 14 seats. But more impressive, in a head-to-head poll asking who is preferred as prime minister, Netanyahu wins with 41% but Gantz is preferred by 38%. This reflects a strong anti-Netanyahu vote looking for a credible alternative to unite around. Gantz is assumed to be broadly centrist, and most of his support appears to come at the expense of Labor and Yesh Atid. Gantz’s security credentials could make him a more credible prime ministerial candidate than other Netanyahu rivals, and draw away some of Likud’s more centrist voters.

• Labor Party leader Avi Gabbay is struggling. In a surprise move, Gabbay dissolved the Zionist Union with Tzipi Livni’s Hatnua (“The Movement”). The Zionist Union formed ahead of the 2015 election under the leadership of Livni and former Labor leader Isaac Herzog. It became the largest opposition party with 24 seats. The list has been losing support for some time and Livni was promoting a merger with other centre and left-wing parties to create a more credible challenge to Netanyahu. For Gabbay, the split will form part of a relaunch strategy that may also include recruiting new candidates, but his actions have divided the Labor Party and its supporters. Livni leads her own Hatnua party, but may seek a partnership with other like-minded candidates.

• The Joint (Arab) List was expected to win 12 seats, which would make it the third (or even second) largest party. Its biggest challenge was expected to be papering over the significant ideological differences within its ranks and encouraging a high turnout among Arab voters. However, on Jan. 8, Ahmed Tibi of the Ta’al party, one of four making up the Joint List, announced he would run independently from the Joint List, throwing these predictions into question.

A number of new parties and candidates have already entered the race, including:

• Orly Levy-Abekasis, a popular Knesset Member (and daughter of 1990s Likud Foreign Minister David Levy) who has split from Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party and established her own social welfare orientated party called Gesher (“Bridge”).

• Moshe ‘Bogie’ Yaalon, a hawkish former IDF Chief of Staff who was sacked as Likud defence minister by Netanyahu in 2016, has formed a new party, Telem (an acronym for “National Statesmanlike Movement”).

• Adina Bar Shalom, an educator (and daughter of late Sephardi Chief Rabbi and Shas founder Ovadia Yosef) is leading a new Ahi Yisraeli, (“Israeli Brotherhood”) party with a social policy and solidarity agenda, though the party is yet to make a tangible impact in the polls. She is joined by Maj. Gen. (res.) Gideon Sheffer.

• Eldad Yaniv, a prominent anti-corruption campaigner and veteran political strategist has formed an anti-corruption party, “Protest Movement”, building on months of protests he has organised against Prime Minister Netanyahu.

© British-Israel Communication and Research Centre (BICOM), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

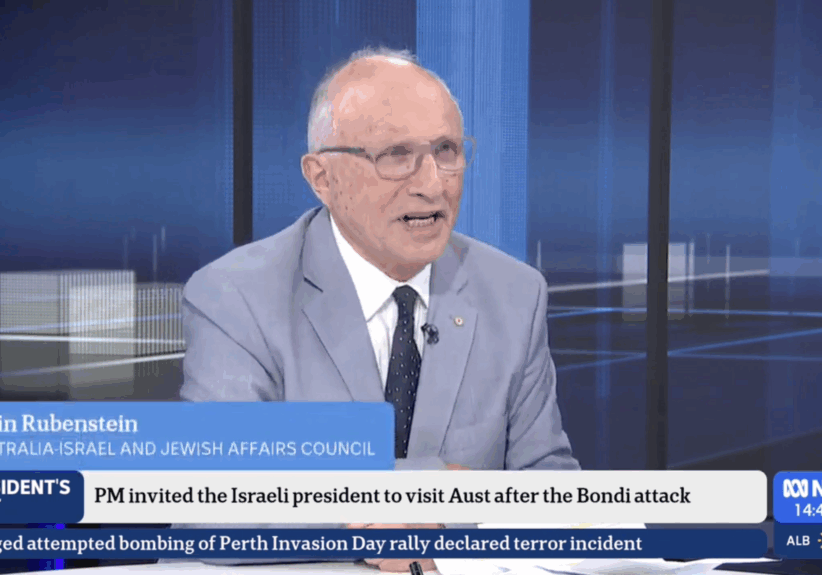

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio