Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: The Other Refugees

Sep 5, 2018 | Ben Cohen

Uprooted: How 3000 Years of Jewish Civilization in the Arab World Vanished Overnight

by Lyn Julius

Vallentine Mitchell, 2018, 368 pp., A$74.95

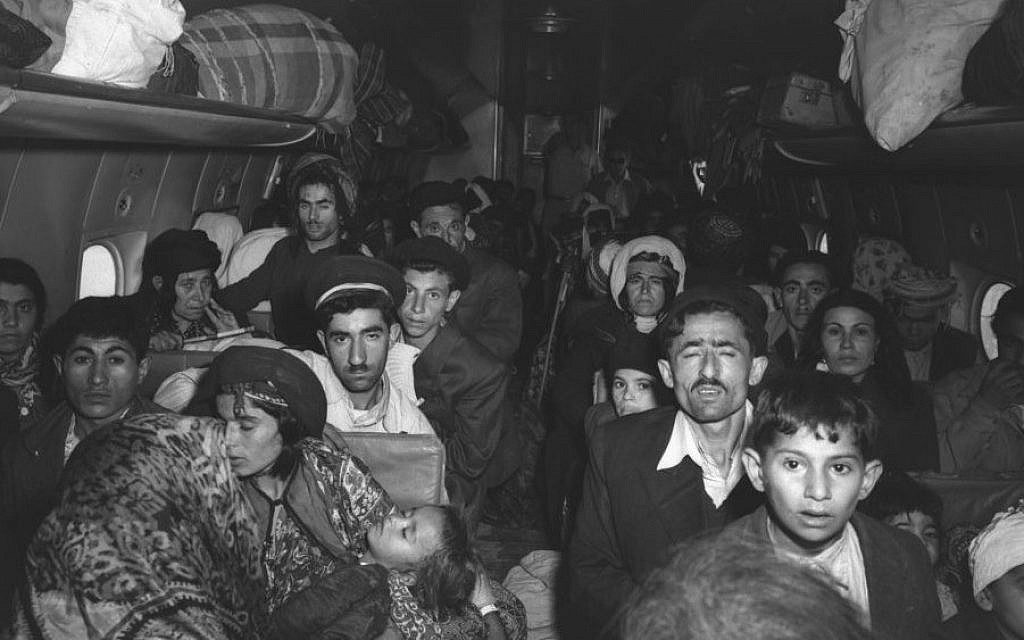

History has been deeply unkind to the Jewish communities of the Middle East and North Africa, and so too has the historical record. As the British author Lyn Julius points out in Uprooted, the persecution and ethnic cleansing of more than 800,000 Jewish denizens of Arab lands from the 1940s onward is a story still confined to the margins of more visible tragedies.

Foremost among these is the Holocaust, commonly regarded as a purely European episode, yet one whose German architects intended ultimately to include the Jews of Arab lands. That ambition was checked when the Allies stopped the Nazi advance in North Africa at the close of 1942.

Then there is the outflow of approximately 750,000 Palestinian Arab refugees during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, still presented in many Western and Arab circles as the origin of the region’s present problems. The Arab refugee issue has become grossly expanded in another way as well: The Palestinians, uniquely among the world’s refugee populations, are compelled by the United Nations to transfer refugee status from parents to children. Thus there are currently five million Palestinian “refugees”.

Because of these events, the Jewish exodus from the Arab world is commonly perceived as simply one more misfortune among the myriad population transfers and ethno-national conflicts that followed World War II. Yet according to the historian Nathan Weinstock, it remains an exodus with no precedent in Jewish history, “even when compared with the flight of the Jews from Tsarist Russia, Germany in the 1930s, or massive emigration from Eastern Europe after the war.”

Julius, herself the product of a Jewish family driven from Iraq, cogently explains how the Jews of the Arab world effectively became denationalised. She argues persuasively that the rapid unravelling of these Jewish communities, whose presence in these areas predated the emergence of Islam, should be understood above all else as an offence against the elementary codes of human rights.

The inherent danger with these kinds of accounts is that the victims end up as a beatified collective, at which point historical writing quickly becomes apologia. Julius avoids this basic trap. She makes it clear that there is no archetypal “oriental Jew,” and no literary sleight of hand can encompass the vastly different experiences of Jews from cowed, closed Yemen and from open, ebullient Morocco. Nor can Cairene Jews, educated in European private schools, be lumped in with those crammed into the Jewish quarters of Fez or Meknes.

Insofar as these communities began exhibiting more and more similarities as the 20th century progressed, it was the result of the draconian, discriminatory legal regimes imposed on them by the Arab governments under which they lived.

By the late 1950s, the vast bulk of these communities, from the western reaches of North Africa to the eastern borders of Saudi Arabia, had been brutally wrenched from their roots. Typical measures along the way included stripping Jews of their citizenship, freezing their property and assets, systematically intimidating them through mass arrests and detentions, proscribing Zionism as a crime, and subjecting them to humiliations both large and petty in the workplace and in schools.

Drawing on the scholarship of historians such as Matthias Kuentzel and Jeffrey Herf, Julius spotlights the ideological overlaps between German National Socialism, the various strains of Arab nationalism, and the overtly antisemitic Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood. “The root cause of the post-1948 exodus of over 850,000 Jews from the Middle East and North Africa,” Julius writes, “was pan-Arab racism, itself influenced by Nazism.”

That truth has become more and more evident as the years have passed, especially in Israel, where historians and politicians are beginning to grasp the significant ties between the Holocaust and the uprooting of the Jews from the Arab world. The clearest example of this trend, which Julius cites approvingly, was the decision by Israel’s Finance Ministry in November 2015 to extend Holocaust-survivor benefits to Israelis who survived Nazi-era persecution in Morocco, Algeria, and Iraq. In the words of Israeli Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon, this was “the righting of a historical wrong.”

If Kahlon’s characterisation appeals to Julius, it is perhaps because she sees her task as correcting a series of historical wrongs that, 70 years after the fact, still confound our appreciation of the Jewish exodus from the Arab world. The critical difference between the Middle East’s uprooted Jews and the Palestinian Arabs is that, excepting a handful of cases from Egypt and Libya, these Jews were never assigned refugee status. This discrepancy, Julius asserts, has “narrowed the [Middle East] conflict to the Israel-Palestinian dispute and excluded the larger Arab context in which the expulsion of the Jewish refugees from the Arab countries is central.”

Israel’s approach to the claims of these Jewish refugees has evolved. The idea of kizzuz – according to which Jewish losses were thought of as being offset by Palestinian losses – has given way to recognition of the judicial importance of individual compensation. Julius credits former US President Bill Clinton for inaugurating this idea in 2000, when he opined that one element of an eventual Palestinian-Israeli agreement would be the creation of a compensation fund for refugees that included “the Israelis who were made refugees by the war, which occurred after the birth of the State of Israel.” Clinton explained: “Israel is full of people, Jewish people, who lived in predominantly Arab countries who came to Israel because they were made refugees in their own lands.”

Julius accepts that the parallel between the Palestinians and the Jews of the Arab world is not a neat one. She believes, in fact, that attempting to draw such a parallel does a disservice to the Jews, who were the targets of government-sanctioned discrimination mainly during peacetime. The Palestinian refugees, by contrast, were displaced as a result of the fierce fighting between the Haganah and the invading Arab League armies. The very act of raising this issue, Julius contends, challenges the “unchallenged sway” that the Palestinian-refugee issue has held thus far. At the moment, “Jewish refugee rights are dismissed as an impediment to peace, denigrated, or ignored, while Arab rights – including the much-vaunted Right of Return – are put on a pedestal.”

As a corrective, Julius puts forward the idea of the Arab world’s Jews as having endured three successive “colonisations.” In the seventh century, there was Islam; in the 19th century, there were European powers; and, finally, in the last century and this one, there has been a “colonisation of facts” by which “the story of the Jews from the Middle East and North Africa has been erased and falsified.”

Uprooted will surely not be the last historical examination of the Arab world’s exiled Jews, but it is among the first to launch a frontal assault on the myths and preconceptions associated with their plight. For that alone, its value will endure.

Ben Cohen, senior editor of The Tower magazine, writes a weekly column for JNS.org on Jewish affairs and Middle Eastern politics. His writings have been published in Commentary, the New York Post, Haaretz, the Wall Street Journal, and many other publications. He is the author of Some of My Best Friends: A Journey Through Twenty-First Century Antisemitism (Edition Critic, 2014). © Commentary (www.commentarymagazine.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: International Jewry, Israel, Middle East