Australia/Israel Review

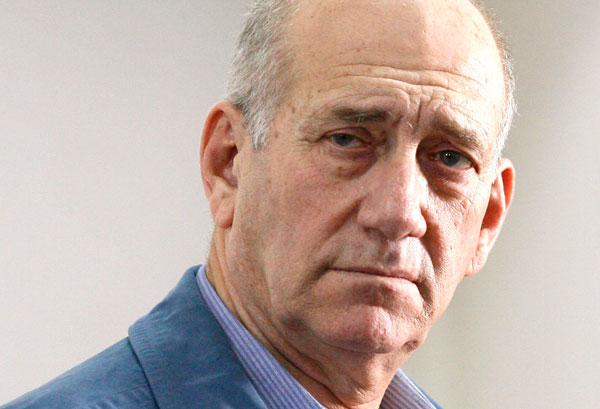

Olmert’s Folly

Apr 14, 2014 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

During 47 years in the public eye, Ehud Olmert has spent more time in and around the court system than any other Israeli politician.

Israel’s twelfth Prime Minister had been repeatedly suspected, investigated and indicted for assorted corruption charges, only to end up cleared, though sometimes with a qualifying asterisk. On March 31, at age 68, his luck ran out, as a Magistrate’s Court in Jerusalem convicted Olmert of taking NIS 500,000 (~A$156,000) as a bribe back when he was Mayor of Jerusalem.

The sentence, which will be announced in late April, will likely include prison time. Olmert is expected to appeal the verdict, but pundits agree that his illustrious political career has now come to its inglorious end.

Olmert first broke into the public conscience in 1966 as a 21-year-old delegate who took to the podium at the Herut (Freedom) Party’s convention and demanded the resignation of its legendary founder Menachem Begin. Seven years on, after having earned degrees in law, psychology, and philosophy, Olmert entered the Knesset, elected to represent a small nationalist faction that subsequently joined the federation that became the Likud.

At 28, Olmert was Israel’s youngest lawmaker. Ironically, he first made headlines as an anti-corruption crusader who exposed the names of reputed underworld kingpins and also waged war on a retired general he accused of collaborating with them.

However, his maverick image, while appreciated by the media and the public, was seen as a problem in his own party. It took him 15 years to get a cabinet position, a politically lost decade and a half for him in which he cultivated a hawkish profile while running a law practice that reportedly specialised in smoothing access to, and getting things done within, government agencies. (Running a private business while simultaneously serving as lawmaker was not illegal at that time.)

By the time he became a minister in 1988 Olmert had already survived his first corruption scandal, and planted the seeds of the next one.

The first brush with the law came when a police investigation into a small bank’s collapse revealed a US$50,000 loan without interest extended to Olmert by the fallen bank’s chairman. The Attorney-General decided not to indict Olmert, but his image as a corruption fighter had been badly dented. Even so, Olmert continued to skate on thin ice.

Olmert first found himself indicted in 1996 over alleged campaign-financing violations as Likud’s treasurer during the 1988 general election, which Likud narrowly won. Olmert was acquitted, but the judge said his conduct was inappropriate. At the time, then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir was grateful for Olmert’s financial services (it is unclear how aware Shamir was that some of Olmert’s methods were legally dubious), promoting him to cabinet rank.

The young minister was therefore tempted to continue exploring the grey area between clever political and financial manoeuvring and crime. His conduct as he continued climbing the political ladder, from Mayor of Jerusalem to Minister of Industry and Trade, and then to Finance Minister – produced a slew of investigations and indictments on assorted allegations, ranging from regular receipt of cash envelopes from a donor and regular double-billings for reimbursements on airplane tickets to unlawfully tailoring the tender of a bank’s sale and to favouritism in the approval of capital-aid requests. Olmert proceeded improbably from the Treasury to the premiership when Sharon fell ill, but three years on, the weight of the multiple allegations he faced were such that he was forced to resign.

Still, Olmert emerged from some of those cases unindicted, from others reprimanded, and from one with a relatively minor conviction for breach of trust – for which he was fined NIS 75,000 (~A$24,000) and received a suspended one-year prison term. At that point his legal situation still seemed compatible with a political comeback, and reports said he was actually contemplating one. But then came the indictment that, if upheld, would finish anyone’s public career – even Olmert’s.

The scandal that came to be known in Israel as the “Holyland Affair” is about a housing project in Jerusalem that is centred on a 32-storey apartment tower that dominates five smaller buildings bordered by several rows of duplexes. All of this was planted atop one of Jerusalem’s highest peaks, in total disregard of the surrounding landscape and Jerusalem’s unique architectural character.

Protruding visibly from miles away, Jerusalemites suspected all along the project was born in sin. Now the court has made the suspicion a fact, convicting among others Olmert and the Jerusalem Mayor who succeeded him for twisting the project’s licensing and approval procedures in return for bribes from Holyland developers.

The conviction is based on one entrepreneur’s state testimony, which was given shortly before he died last year. According to the conviction, the state witness transferred NIS 500,000 (~A$157,000) to Olmert’s brother, and made additional payments to Olmert’s secretary and to the City Engineer, the official in charge of building licenses.

In addition, Olmert was also convicted of receiving, as Minister of Trade and Industry, a NIS 60,000 (~A$19,000) bribe from a senior banker in return for extending leasing rights for coastal farmland and re-zoning the land to allow much more lucrative commercial and residential use.

Olmert’s downfall is seen in Israel as a tragedy that is primarily reflective of a flawed personality, but also as part of a Zeitgeist – a late side effect of Israel’s great transition in the 1980s from a mainly socialist to a mainly capitalist economy.

As Israel parted with its ascetic founders’ appreciation for simplicity and modesty, their ethos was replaced by a new legitimacy for luxury and status-symbols which for some now became an obsession. Olmert may be viewed as a symbol of this cultural transition.

At the same time, Olmert will also be remembered as a born-again centrist and a clever pragmatist, one who was, in 2008, ready to deliver a peace agreement with the Palestinians, which his Palestinian interlocutor, Mahmoud Abbas, proved unable to accept.

Back when he succeeded Sharon, Olmert said he planned to make Israel leave the West Bank as unilaterally as it had just left the Gaza Strip. The following year’s Second Lebanon War made him quietly shelve that plan, tacitly conceding that unilateral retreats tend to be followed by rocket attacks on Israeli towns.

The fighting in Lebanon, too, was emblematic of Olmert’s mixture of resolve and improvisation. On the one hand, the fighting did not go as smoothly as he had apparently thought it would, and at the war’s conclusion, he was widely viewed as having acted without sufficiently clear goals or adequate strategic planning. On the other hand, the conflict nonetheless sent the message to Lebanon and Hezbollah that Israel will respond to provocations harshly. The resultant quiet along the Lebanese border is now more than seven years old.

Olmert also happened to have been at Israel’s helm when the 2008 meltdown rattled the global economy. He passed that test with flying colours, keeping the budget tight while also managing to keep the shekel strong and unemployment minimal. He was able to quickly restore GDP growth after a mere two negative quarters. It was an economic performance no government in Europe or America at the time was able to match.

Lastly, a father of four who, together with his wife of 44 years Aliza, adopted a fifth child, Olmert is an outgoing, affable man who quickly makes friends, has an astonishing memory for names and faces, and sincerely wants to help people when he learns of their problems. Had it not been for his run-ins with the law, his leadership might well have been long-lasting and significant for Israel.

Sadly, while as a leader he certainly deployed his affability to court power, he was brought down because he lost his fear of the power of the court.

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio