Australia/Israel Review

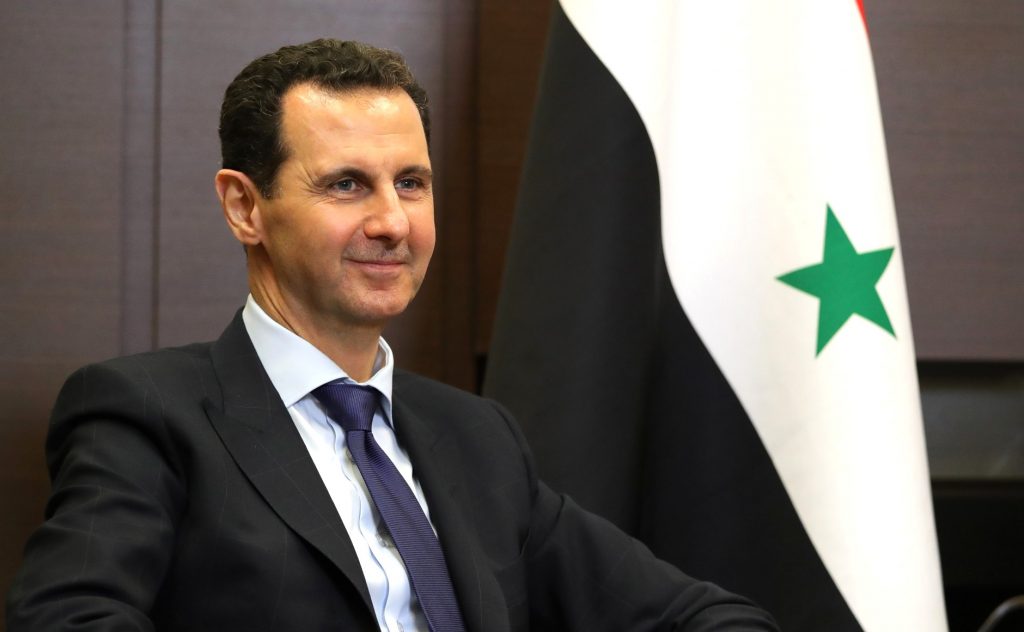

The road back to Damascus

Nov 25, 2021 | Amotz Asa-El

“Stop the killing machine!” demanded Saudi King Abdullah of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, as Riyadh withdrew its ambassador from Damascus.

It was August 2011 and the Syrian civil war was hardly six months old, but with the Assad regime’s attacks on its own citizens well underway, the richest Arab country launched a pan-Arab effort to remove Assad, explaining that his war against what appeared to be most Syrians had “nothing to do with religion, or values, or ethics.”

The campaign’s rationale was clear, both in terms of its aim and in terms of its prospects. The previous months’ upheaval in multiple Arab capitals could easily spread further, and possibly threaten regimes like Saudi Arabia’s. At the same time, with the leaders of Egypt and Tunisia already ousted, and the downfall of their Libyan and Yemeni counterparts imminent, adding a fifth name to that list was not unrealistic.

The Saudi move was soon followed by Bahrain and Kuwait, then by the rest of the Gulf’s monarchies, and then by the Arab League as a whole, which suspended Syria’s membership and imposed sanctions on the Assad regime in November 2011.

Eighteen Arab countries backed that resolution, with only Syria and Lebanon opposing it, and Iraq abstaining. A diplomatic exodus then ensued, as 18 Arab embassies in Damascus were shuttered, scores of Syrian diplomats were returned home, and the Syrian economy, already crippled by the war and by American and European sanctions, was boycotted by most of the Arab world, as well.

It was part of a broad international campaign, led by the US and France and joined by all Western countries as well as Turkey. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan repeatedly called Assad a “butcher,” as did then British PM David Cameron and then French President François Hollande.

Assad survived this pressure, and indeed, in the cases of Cameron, Hollande and US President Barack Obama, has not only outlasted all these leaders, but their successors as well.

Now, a decade after Syria’s suspension from the Arab League, signs are mounting that Arab leaders are increasingly accepting Assad’s survival and re-legitimising his rule – a policy shift that is sending tremors across the region, from Ankara to Teheran.

The first glimmer of retreat from Syria’s excommunication began in December 2018, when then-Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir landed in Damascus.

Though Bashir was himself a pariah in much of the world, having been indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes in his own country’s civil war, his visit clearly happened with Riyadh’s blessing, the Saudis having previously mended fences with him.

Shortly before Bashir’s visit, Bahrain’s Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa publicly shook hands with then-Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem – a gesture that could not have happened without Riyadh’s acquiescence.

The Saudi strategic decision to re-engage with Damascus really became clear several days after Bashir’s visit, when the United Arab Emirates, another close Saudi ally, reopened its embassy in Damascus.

Subsequent events amounted to a thoroughgoing retreat from the Arab world’s diplomatic and commercial boycott of Syria after 2011.

In January 2019, Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita called for “Arab coordination concerning Syria’s return to the Arab League.” In May 2020, Arab media reports claimed the Saudi chief of intelligence Khalid al-Humaidan secretly visited Damascus and met with Assad. This past September, Jordan reopened a border crossing south of Daraa, the Syrian town where the civil war began, and in October, Jordan’s King Hussein took a phone call from Assad. In early November, Emirati Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed visited the Syrian President at his palace, amid Arab media reports that Riyadh has decided to restore full diplomatic ties with Damascus.

What, then, is driving this evolving thaw?

The first factor underpinning the Arab rehabilitation of the Assad regime is political. Last decade’s uprisings in multiple Arab capitals traumatised political elites across the Mideast. No issue is more urgent from their point of view than the threat Islamist fundamentalism poses to their own survival.

Yes, having bombarded and gassed thousands while presiding over a war that took more than half-a-million lives, Bashar Assad is effectively responsible for the killing of more Arabs than anyone else in recent history. And yes, his secret services tortured and executed many others, while his air force levelled neighbourhoods, hospitals, and schools. And yes, the displacement of more than 10 million Syrians that Assad’s forces and allies caused constitutes the century’s worst refugee crisis.

Yet the hard reality is that religiously moderate Syrian opposition groups failed to unite, and certainly failed to win, thus leaving the fundamentalists as the only viable alternative to Assad. And the prospect of Syria falling into Islamist fundamentalist hands is, from the viewpoint of Arab governments, the worst-case scenario.

That is what Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi meant when he said, back in 2016, that Cairo’s policy is to “support national armies,” whether in Libya, Iraq, or Syria, thus listing Arab countries whose armies are challenged by assorted militias.

Beyond this domestic consideration lurk two geopolitical concerns – one regarding outside global powers, the second, regional powers.

The role of the global superpowers in the Middle East has transformed dramatically since the civil war’s outbreak. Back then, Russia was on the region’s margins, where it had been since Egypt’s defection from Moscow’s orbit to Washington’s in the 1970s.

This configuration ended in 2015, when Russia opened the Khmeimim airbase in western Syria and thrust its air force into the thick of the Syrian civil war – and soon determined that war’s outcome.

The Obama Administration’s failure to oppose the Russian move, even verbally, alongside Obama’s failure to follow through on his threat to punish Assad for launching chemical weapons attacks on his own people, led Arab leaders to conclude that Washington’s strategic domination of the Middle East was being seriously challenged, and possibly eclipsed, by Moscow. Russia’s agenda therefore won new respect, and the first item on that agenda was the preservation of the Assad dynasty – which has been loyal to Moscow since its establishment in 1971, and provided Russia with a Mediterranean naval base at Tartus, a precious asset from the Russian point of view.

At the same time, Arab governments are also being pushed back toward Assad’s presidential palace by two regional players, Turkey and Iran.

Turkey initially hoped to see Assad fall and be replaced by a Sunni fundamentalist regime that would be a satellite for Ankara. Like the rest of the world, when Turkey realised that Assad was likely to survive the war, it changed its attitude.

Diplomatically, following the Russian intervention in the Syrian civil war, Turkish President Erdogan reversed course and said that Assad could play a role in forging Syria’s future.

Militarily, Ankara shifted its focus from reshaping Syria to stifling the Kurdish autonomy that the war had produced along the Turkish-Syrian border. Turkey has thus invaded northern Syria in several offensives since 2016, and its troops now occupy more than 8,000 square kilometres on the Syrian side of the 900km Turkish-Syrian border.

To Arab leaders, this Turkish occupation brings to mind memories of the Ottoman Empire’s 400-year rule over the Arab world. Seen through this prism, Assad’s struggle appears to be part of a greater Arab cause.

That cannot be said of the other regional power at play in the Syrian-Arab rapprochement: Iran.

Iran, from Assad’s viewpoint, is not an intruder, but a true ally. Throughout the civil war, the Islamic Republic stood by Syria through thick and thin, supplying it with Shi’ite militia troops from Lebanon, Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan that fought – and got killed – in large numbers for Assad, as well as with sorely needed oil and cash.

For most other Arab governments, led by Saudi Arabia, Iran is the strategic arch-enemy. Analysts therefore believe that hopes of driving a wedge between Damascus and Teheran are a major motivation for the Arab return to Syria.

A recent unconfirmed report by Al Arabiya news agency has claimed that Assad intends to fire the commander of the Iranian forces in Syria, Javad Ghaffari. Whatever this report’s accuracy, Israeli analysts believe Assad is growing impatient with Iran’s extensive military activity and bases in his country and the repeated attacks they draw from the Israel Air Force.

This impatience is believed to be shared by Russia as well, a sentiment that may explain Vladimir Putin’s decision to stretch out his first meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett in Sochi in October from three to more than five hours.

Whatever was discussed there, three days later Israeli jets struck Iranian-backed units in southwestern Syria, opposite Israel’s Golan Heights border, and this has been followed by weeks of increased Israeli attacks on Iranian targets in Syria. It seems Russia had to have been in the know.

The anti-Iranian dynamic became glaring the following month, when Emirati and Bahraini warships joined Israeli and US vessels in a multilateral naval exercise in the Red Sea.

This was an Arab-Israeli show of military harmony that until recently was unthinkable – as unthinkable as a renewed pan-Arab embrace of Bashar Assad and his regime.

Tags: Middle East, Syria