Australia/Israel Review

The Last Word: Enemies of The People

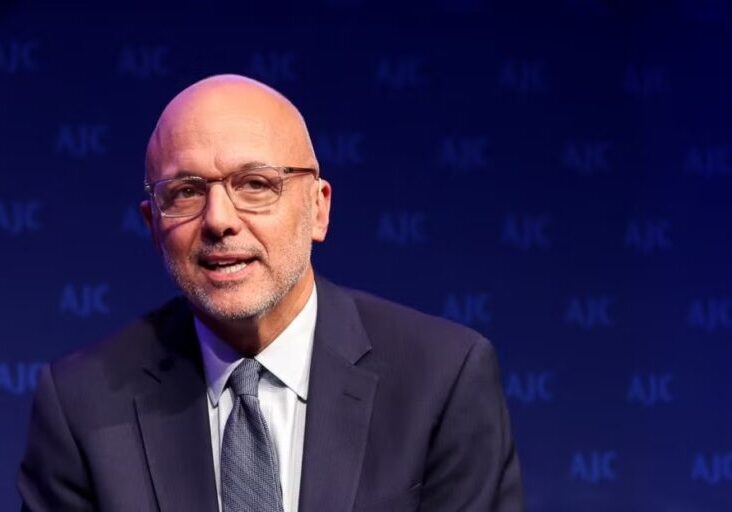

Jun 28, 2019 | Jeremy Jones

What does it mean to be an “Enemy of the People”?

This question arose numerous times during my recent visit to Italy, the Balkans and the USA.

In Rome, members of the Jewish-Catholic International Liaison Committee (ILC), including myself, met with refugees who had no real option other than leaving their countries of birth and residence, having been subjected to vilification, dehumanisation and physical attacks.

Discussing the issue of attacks on both religious freedom and religious minorities, the ILC noted that the same forces could be seen to be at work – people defining opponents not simply as wrong but as not worthy of being treated with any respect nor accorded basic rights.

In discussions on antisemitism, the concept of Jews not simply as an “other” to be despised, but as an existential “enemy of the people”, was examined as an idea having currency in a number of countries across five continents.

Meeting with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, I had the opportunity to discuss the concerns over the growth of exclusivist nationalisms and also to note the benefits to Australia of multiculturalism as a model to enhance the opportunities of all to contribute to the maximum of their ability.

In Albania, I attended a significant international conference at the National History Museum, which bore the title “Enemy of the People”.

Under communist totalitarianism, this label led to deprivation of liberty and livelihood, with the dictatorship also using the phantom presence of such people as justification and rationalisation for censorship and restrictions on movement, speech and association.

It was in Tirana that I met with Rexhep Hoxha, who starred in the movie Besa, which told the story of his own extended family and other Muslim Albanians who acted with such courage and nobility to save Jewish lives during the Second World War.

For the Nazis, not just Jews but anyone with basic compassion was an “enemy of the people”.

Under communism, those who practised religion were also “enemies” of the secular “people” – and it was instructive to discuss the rebirth of a multi-religious society with Muslim, Christian and Jewish scholars in both Albania and North Macedonia.

The capital of North Macedonia, Skopje, receives countless tourists as it is the birthplace of Saint Teresa (Mother Teresa) of Calcutta, but religious identity in that country goes well beyond efforts to attract foreign visitors.

The Albanian Muslim minority has an impressive scholarly centre and a motivated leadership.

Alert to the opportunity of building bridges and setting an international example, the Muslim leadership invited me to speak at their Iftar [dinner to end the daily Ramadan fast], to which prominent Jews of North Macedonia had also been invited.

In the centre of Skopje, there is an impressive Museum of Jewish history and the Holocaust, which tells the story of the way an essential element of society in the area, the historic Jewish community, had been isolated and dehumanised prior to their genocide.

When I met Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, I was able to talk about the value of cultural diversity and pluralism to his country as it is to mine, as well as outlining the opportunities accorded to me to meet Jewish, Muslim and Christian leaders for dialogue and bridge-building.

Before returning to Australia, I participated in the Global Forum of the American Jewish Committee, in Washington DC.

At this conference also, the issue of exclusionist politics, vitriol masquerading as public discourse and the destructive effects of the latest manifestations of identity politics emerged as serious domestic and global concerns.

From militant sections of the left and the right, “enemies” are being identified with an almost religious fervour, while we are still witnessing literal religious fervour aimed at those identified as not merely “enemies of the people” but enemies of God.

In Australia, as elsewhere, the language, and more importantly the mindset, of those who vilify and dehumanise those with whom they disagree is a very real, very serious challenge to the fabric of our society.