Australia/Israel Review

The Biblio File: A Greek Tragedy in Persia

Aug 1, 2011 | Tzvi Fleischer

Tzvi Fleischer

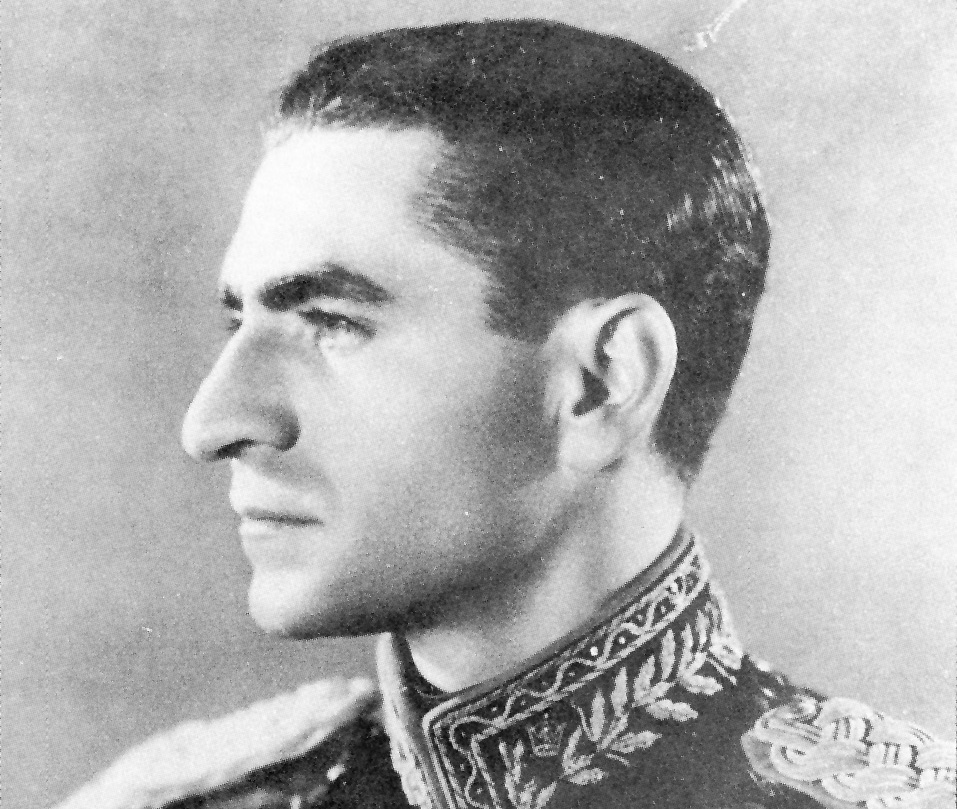

The Shah

by Abbas Milani, Palgrave-MacMillan, 467 pp, $34.95

In 1977, Abbas Milani, then a US-educated lecturer at the National University of Iran was arrested by Iranian security forces loyal to the Shah as a result of his authorship of anti-regime pamphlets. He was given over to the far-from-tender mercies of the Komiteh [“the Committee to Fight Terrorism”], one of Iran’s thuggish security services. In 1996, Milani wrote of his Komiteh interrogator, “In the past eighteen years, rarely has there been a day or night in which the memory of his threats, his punch, and the fierce look in his eyes has not haunted me.” After a peremptory trial, Milani was jailed for one year, including three weeks in solitary confinement, at Teheran’s infamous Evin Prison. (He would likely have received a harsher sentence if his case had not attracted attention in the West). He shared his imprisonment with such later luminaries of the subsequent 1979 Islamic Revolution as future President Ali Hashemi Rafsanjani and Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, who became Khomeini’s designated successor in 1985 before falling out with him in 1989.

Now, Milani – who escaped Iran to go on to become Director of Iranian Studies at Stanford University – has written the best English-language biography of the man in whose name he was imprisoned and tortured – Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran from 1941 to 1979.

Despite the horrors visited on Dr. Milani in his younger years, the Shah whose portrait he paints is, if not a wholly sympathetic figure, at the very least one for whom he has a certain empathy.

Milani’s Shah is a man very ill-suited to the role thrust upon him, a quiet sensitive boy, a weak personality very much in the shadow of over-powering parents. His father, Reza Shah, the founder of the dynasty, was a poorly-educated but highly charismatic, swashbuckling army officer who staged a 1921 coup to first make himself Prime Minister and then went further and deposed the decadent and powerless Qajar dynasty and made himself Shah. Mohammed Reza’s mother, Taj-al-Muluk, domineering and devout, seems to have had a personality at least as powerful and wilful as Reza Shah, and was estranged from his father virtually from the time of Mohammed Reza’s birth. But from his father’s coronation in 1925, he was largely removed from her care and placed under the oversight of his stern and demanding father.

In 1941, the British tired of the ostensibly “neutral” game that Reza Shah was playing during World War II. Determining that his ongoing flirtation with the Germans was strategically intolerable, a swift military intervention was staged, and Reza Shah was forced into exile a broken man, dying soon afterwards. There was serious consideration given by Whitehall to restoring the Qajar dynasty, whose heir, Prince Hamid, was a British citizen serving as an officer in the Royal Navy. The idea was dropped primarily because it emerged that Prince Hamid spoke no Persian. Thus, a nervous and ill-prepared 21-year-old Mohammed Reza Shah was allowed to take his father’s place on the Peacock Throne under strict British tutelage.

The rest of the book reads somewhat like a fascinating, real life version of a Greek tragedy – though Milani is careful not to overdo the tragic theme at the expense of accurate historical detail. The Shah, precisely and paradoxically because he was ill-suited to his role as monarch, came to see himself as indispensable. There were many opportunities to take a different route – to become a constitutional monarch, but Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was determined that he would not allow this under any circumstances – perhaps to prove to his absent, stern and accusing father that he indeed had the stuff of kingship in him.

The Shah was a playboy, addicted to fast cars, fast planes, beautiful women, artificial honours and expressions of admiration for his supposed “genius”, as well as ridiculously extravagant banquets. He was also an extremely hard worker on behalf of the Iranian people, and his achievements in dragging Iran toward a modern society, financed by oil wealth, were actually pretty remarkable. As Milani makes clear, by the 60s and 70s, Iran was, by Middle Eastern standards, a relatively liberal country offering extensive cultural freedom and religious tolerance, a much improved and improving standard of living, including considerable individual liberty – except in the political sphere, where despotism and repression predominated.

The Shah’s fragile ego, his early experiences with political opposition, his inability to relinquish any political power, his intolerance of prime minsters with ambition and initiative, and his increasing tendency to simply dismiss all opposition as something to be steamrolled led to this increasingly authoritarian rule, reliant more and more on the repression of the secret police, especially the notorious SAVAK. His tragedy is that his personal flaws meant that his quest for a modernised Iran was carried out in a way that guaranteed that both the new interests groups created by modernisation – such as the middle class and the intelligensia – as well as the forces of tradition opposed to modernity’s disrupting influence, eventually united against his rule. The latter eventually won the power struggle and created the Islamic Republic, more repressive than the Shah’s regime ever was and a negation of many of his achievements.

One of the important points made clear in the Shah’s story is that the continuing paranoia Iranians tend to exhibit about foreign conspiracy to control their country is actually grounded in genuine experience. The extent to which the British controlled, and engaged in conspiracies to control, all aspects of Iranian government and economic policies from 1930s through the late 1950s, is truly astonishing to anyone not familiar with the details of Iranian history. Meanwhile, the Americans also played the same game extensively in the 50s and 60s. Iranians may be paranoid, but they do have some reason to be.

Another lesson one can draw from this book is that the roots of modern Islamist terrorism are pretty deep in Iran, and have played a significant role in Iranian politics since the 1940s. A key player in the history of Iran under the Shah was a terrorist group called Fedeyeen Islam, associated with the radical cleric, Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Mostafavi Kashani, and later, with Ayatollah Khomeini. Islamist terrorists associated with this organisation repeatedly assassinated key players in Iranian politics, including charismatic Prime Minister General Haj Ali Razmara in 1951, Court Minister Abdol-Hussein Hajir in 1949, Education and Culture Minister Ahmad Zangeneh in 1951 and Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansour in 1965. An attempt by the group to assassinate the Shah in 1949 failed only thanks to the dumbest of luck.

Good as this book is, it does have some flaws. The copy I read certainly needed much better editing. There was scarcely a page without an annoying clanger of one sort or another – a word missing, a mis-spelling, an inconsistent spelling, a sentence which made no sense. There were also at least two places I found where whole sections of text – amounting to several paragraphs – were simply duplicated. (The version I have is an advance review copy with a disclaimer that it is an “uncorrected version of the book”, so hopefully some or all of these flaws have been corrected in the version available for commercial sale.)

More substantively, the book could have been clearer regarding a central episode of the story of the Shah and his tragic descent into authoritarianism. While Milani does not articulate it in so many words, it is clear that one key reason for the Shah’s behaviour during the final years of his rule – the repression, the staunch refusal to even consider moving toward a model of constitutional monarchy – lies in the events of 1950 to 1953, when the charismatic Mohammad Mossadeq and his populist National Front party increasingly contended with the Shah, and attempted to force him into a purely ceremonial role. Of course, the broad outline of this story is widely known – Mossadeq making the nationalisation of Iranian oil the key plank of his popular and populist quest, becoming PM despite the Shah’s reluctance and British opposition, and eventually briefly forcing the Shah into exile in August 1953 before being overthrown by a Western-supported coup. Unfortunately, however, Milani fails to make understanding the detail of the contest between Mossadeq and the Shah an easy task. Many incidents in this struggle are skipped over or described out of chronological order, making it difficult to get a complete sense of how this vital element in the tragic story of the Shah, and his eventual replacement by the Islamic Republic, unfolded.

Nonetheless, this book remains essential background for comprehending the events of 1979. As Dr. Milani notes, “The paradox of the fall of the Shah lies in the strange reality that nearly all advocates of modernity formed an alliance against the Shah and chose as their leader the biggest foe of modernity.” If you want to understand how this bizarre paradox came about, and indeed, the development of the Islamic Republic in the years since 1979, this book should be required reading.

Tags: Iran