Australia/Israel Review

The Appeal of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia

Sep 24, 2014 | Giora Eliraz

Giora Eliraz

A pivotal doctrinal slogan proclaimed by the militants of the Islamic State (IS) – formerly known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) – is re-establishment of a Caliphate (Khilafah) that binds together lands inhabited by Muslims under unified political rule, based on Sharia Islamic law. For this purpose, the ISIS declared itself in June 2014 as Islamic Caliphate; its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as Caliph, and changed its name.

ISIS’ concept of a Caliphate actually goes hand in hand with a strong sense of disgust towards the Franco-British Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916. Understanding that the end of the Ottoman Empire was very near, Britain and France agreed via this treaty to divide between themselves areas of control and influence in Arab provinces of the declining Muslim empire of the Ottomans. When ISIS militants erase the border between Iraq and Syria in areas under their control, they are in fact attempting, from their perspective, to smash the Western-imposed concept of nation-states and borders in Muslim lands.

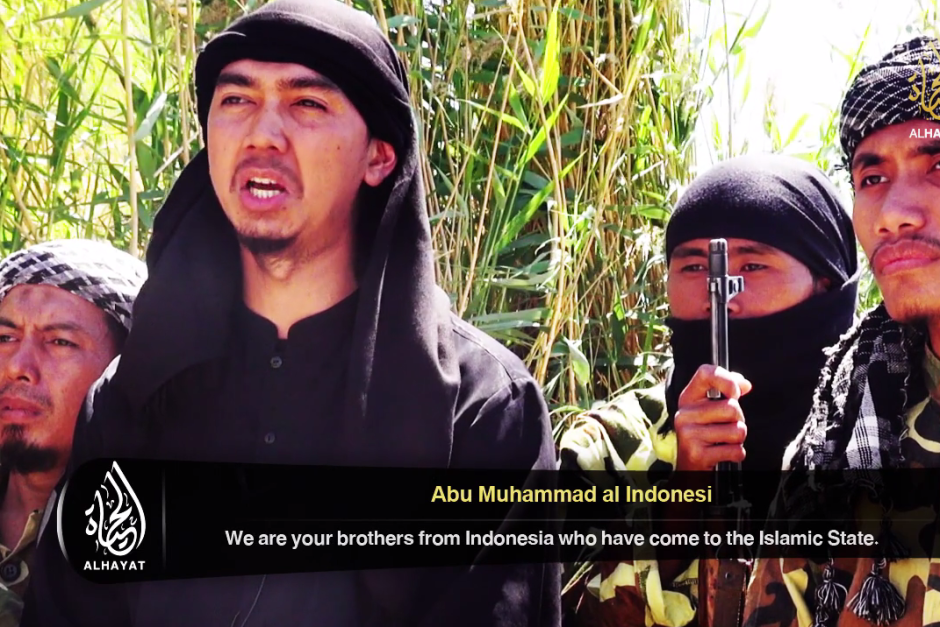

Thousands of foreign fighters have already joined the battlefields of Syria and Iraq, especially the ranks of IS. Southeast Asia, or more precisely the Malay-Indonesian world plus Australia, have not been left untouched. Young people from these areas also fight with Islamist extremist groups in Syria and Iraq, including for the IS, which is said to enjoy increasing support and popularity among hard-line Islamists in Southeast Asia.

The vision of establishing a Caliphate is not strange to radical Islamists in Southeast Asia. Moreover, this vision has been re-actualised since the early 2000s by the infamous terrorist network Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), which aimed to create an Islamic state, or Caliphate, in the Southeast Asia region. But in that case the concept of establishing a Caliphate was anchored in the regional context, namely Southeast Asia, where no real caliphate has existed historically as a political entity. As such, it differs somewhat from the much more common vision of re-establishing the Caliphate in the Middle Eastern context, which expresses a yearning to return to the golden age of Islam which once flourished there.

Obviously, militant Muslims in the Malay-Indonesian world are inspired now by the establishment of Islamic State in the hub of the Muslim world. Abu Bakar Bashir himself, alleged to be the former spiritual leader of the JI and to have formed the terrorist group Jamaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT) in 2008, was himself reported to have voiced support for ISIS in July and then even to have pledged allegiance a month later to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Reportedly, this latter move by Bashir, who is currently serving a prison sentence in Indonesia on terrorism charges, was rejected by leaders and members within the JAT for ideological reasons and caused them to form a new group, Jamaah Ansharusy Syariah (JAS).

It should be noted that a vision of re-establishing a Caliphate with clear Middle Eastern roots is not restricted to militant Muslims in Southeast Asia and Australia; such a vision has been prominent for years in the Islamist discourse including amongst non-violent Islamist groups and circles. Salient among them, in Indonesia and Australia in particular, is the transnational radical Sunni Islamist movement originally known as Hizb al-Tahrir al-Islami (Islamic Liberation Party) – now known widely as Hizb ut-Tahrir.

This movement has had deep roots in the Middle East since the1950s. It has branches in many countries, including an open presence in most significant Western countries. The idea of unifying Muslim lands under Caliphate, ruled strictly by the Sharia, is central to the doctrine of this movement. Its propagation largely aims at young people; it preaches by making use of the freedom of expression offered by democracies even though the movement strongly opposes the concept of democracy, viewing it as a product of rejected Western-oriented secular and liberal thought and values. It also rejects religious pluralism insofar as it entails religious equality, and also opposes gender equality.

Hizb ut-Tahrir forbids the use of violence and armed struggle for achieving its goals. It has also criticised ISIS, mainly on religious and political grounds, for declaring itself as an Islamic Caliphate and its leader as Caliph. Yet, on the other hand, one cannot exclude the possibility that young people who have been widely exposed to a vision of a restored Caliphate propagated by radical Islamist groups that oppose violence, like Hizb ut-Tahrir, could be receptive to recruitment efforts by militants who demonstrate zealous commitment to turn the vision of a re-established Caliphate into a reality in the Middle East.

In addition, like ISIS, the Hizb ut-Tahrir movement rejects the Sykes-Picot agreement and the current nation-states that this agreement ultimately led to – portraying it, among other things, as a “crime”, “infamous”, a “colonial project”, and an act of the “unbelievers” that aimed at dividing the Umma, the entire community of Muslim believers.

There is an intrinsic tension in almost every ideological movement between abstract ideas on the one hand and tactics for concrete realisation on the other. Young people tend to prefer actions over words, especially those who have only shallow understanding of a given ideology, canon or religion and are unversed in its sophisticated doctrinal arguments.

When young people worldwide, including from Southeast Asia and Australia, join the battle on behalf of Islamist groups, they doubtless do it for a variety of reasons. The international propagation of that old vision of restoring the Caliphate – often inter-woven with anti-Western colonial sentiments – almost certainly plays a significant role, especially at this time.

Dr. Giora Eliraz is a Research Associate at the Harry S. Truman Institute at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Affiliated Fellow at KITLV/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies in Leiden, and Research Fellow at the Institute for Counter-Terrorism at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya. He specialises in the study of extremism in Southeast Asia.