Australia/Israel Review

Iran’s game of nuclear chicken with Biden

Mar 2, 2021 | Lazar Berman

With each step Iran takes to advance its nuclear program, a path out of the dangerous quagmire becomes even more murky.

On Feb. 23, Teheran officially suspended its implementation of the Non-Proliferation Treaty Additional Protocol, which gave nuclear inspectors increased access to Iran’s nuclear program, including the ability to carry out snap inspections at undeclared sites.

“As of midnight tonight, we will not have… commitments beyond safeguards. Necessary orders have been issued to the nuclear facilities,” said Kazem Gharibabadi, Iran’s envoy to international organisations in Vienna.

A day earlier, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said that Teheran could enrich uranium to 60% purity if it so desired. US State Department spokesman Ned Price said the comment “sounds like a threat” and referred to it as “posturing.”

Analysts believe both the move to limit inspections and the enrichment threat are aimed at bolstering Iran’s negotiating position as it and US President Joe Biden’s Administration manoeuvre ahead of expected talks aimed at bringing Washington back into the 2015 nuclear deal. But even if intended as bargaining chips, they carry the risk of moving Iran significantly closer to nuclear weapons capabilities.

“Biden is playing a game of chicken over who will reverse course first,” said Joab Rosenberg, former deputy head analyst in the Israel Defence Force’s Military Intelligence Directorate. “There is an extremely unstable situation here, and a vector of deterioration and Iranian progress toward a bomb.”

The 2015 nuclear deal limits the Islamic Republic to 3.67% enrichment, a threshold it long ago passed as part of a series of escalating violations of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action between Iran and six world powers, better known as the Iran nuclear deal.

Uranium enriched to 60% is short of what Iran needs to make a nuclear weapon, but it would show that Teheran is going beyond the 20% to which it began enriching in January.

Levels above 20% are considered highly enriched uranium, or HEU, with few non-military uses. The jump from 20% to 90% enrichment, the level needed for most weapons-grade applications, is fairly simple, and any move to begin enriching above 20% is liable to raise major alarm bells.

In 2013, Iran’s parliament pushed for a bill to enrich to 60%, which it said was allowed for nuclear-powered submarines. At the time it claimed it was developing such naval vessels, but today is not known to have any in its fleet, raising suspicions that the plans had been a feint.

While Iran’s nuclear program progresses, the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) ability to keep an eye on Teheran’s nuclear program is moving in the other direction. On Feb. 21, IAEA chief Rafael Grossi told reporters after an emergency trip to Teheran that Iran’s Government would begin offering “less access” to UN weapons inspectors – involving unspecified changes to the type of activity the watchdog can carry out.

“It is totally clear that from Tuesday [Feb. 23], the oversight of Iran will be damaged,” said Rosenberg.

The move to restrict inspectors was in line with a law passed by Iran’s parliament in December requiring the Government to cease implementation of the Additional Protocol.

“This law exists, this law is going to be applied, which means that the Additional Protocol, much to my regret, is going to be suspended,” Grossi said, referring to a confidential inspections agreement between Teheran and the IAEA reached as part of the nuclear deal.

Teheran has been gradually suspending its compliance with most of the limits set by the agreement in response to Washington’s abandonment of the nuclear deal, which provided sanctions relief in exchange for enrichment restrictions, and the failure of other parties to the deal to make up for the reimposed US penalties.

In July 2019, Iran announced it had exceeded the 300 kilogram limit of its 3.67% low-enriched uranium stockpile. A week later it began enriching uranium to 4.5% at the Natanz plant.

In September of that year, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced that “all of the commitments for research and development under the JCPOA will be completely removed by Friday.” The IAEA verified in November that Iran’s heavy water stockpile had exceeded the JCPOA’s 130 metric ton limit.

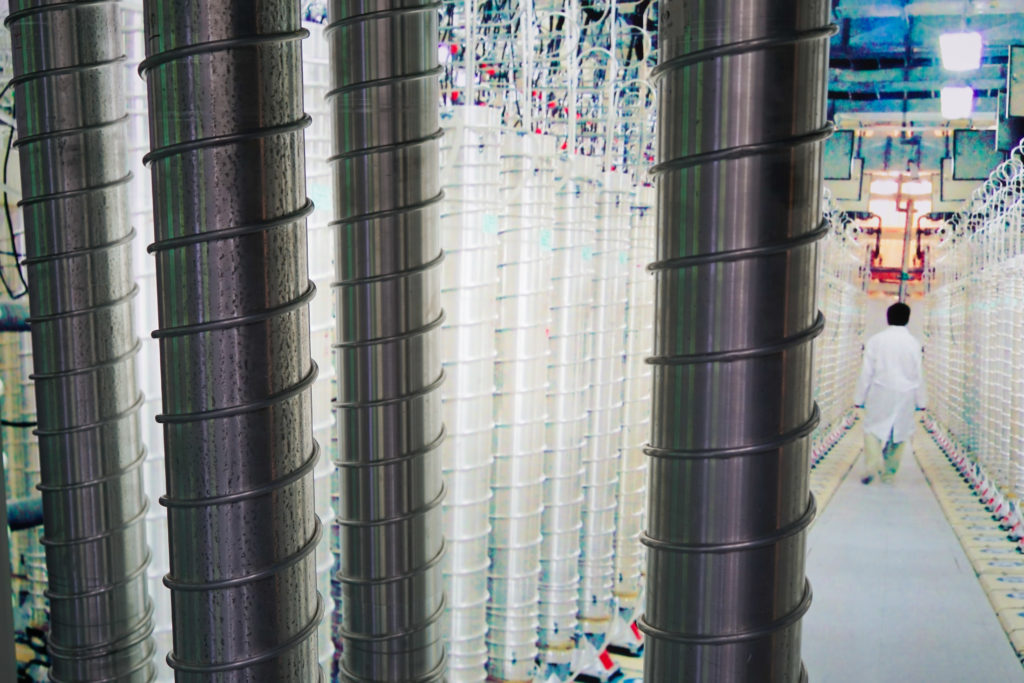

On Jan. 5, 2020, Iran announced its fifth planned violation, forgoing any limits on the number of centrifuges it operates.

In January 2021, Teheran revealed that it was taking steps to produce uranium metal, days after it resumed enriching uranium to 20% purity at the underground Fordo facility.

According to a report on Feb. 19, IAEA inspectors last summer found uranium particles at two Iranian nuclear sites to which Iran tried to block access.

Iranian authorities had stonewalled the inspectors from reaching the sites for seven months before the inspection, and Iranian officials have failed to explain the presence of the uranium, the Reuters news agency reported, citing diplomats familiar with the UN agency’s work.

The inspections took place in August and September of 2020, the report said. The IAEA keeps its findings secret and only shared the details of the find with a few countries.

The Wall Street Journal reported the suspicious findings earlier this month, without identifying the material.

IAEA chief Grossi tried to put the Feb. 21 agreement on inspections in a positive light, stressing that monitoring would continue in a “satisfactory” manner, pointing to a three-month “technical understanding” reached to ensure some type of inspections would continue.

“My hope, the hope of the IAEA, has been to stabilise a situation that was very unstable. And I think this technical understanding does it, so that other political consultations at other levels can take place,” Grossi told reporters.

But the IAEA has refused to detail what the deal allows, and critics fear that it will still give Iran more leeway to make progress in its nuclear program while dictating what kind of access international inspectors will have.

“Based on Grossi’s evasiveness, it doesn’t seem like he achieved much in this agreement,” said Rosenberg.

He noted the possibility that Iran actually made more significant concessions but that Grossi agreed not to go into detail so as not to arouse criticism of the Government from Iran’s parliament, which nonetheless termed the agreement “illegal”.

Richard Goldberg, a senior adviser at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, assailed the lack of demands for clarity from the White House.

“The US should not accept that the terms of this agreement are secret,” he said.

While the Administration of former US President Donald Trump had pursued a “maximum pressure” policy against Iran, Biden has signalled a more conciliatory approach, albeit while leaving the reimposed sanctions in place. On Friday, Biden said the US was “prepared to reengage in negotiations with the P5+1 on Iran’s nuclear program.”

Goldberg said the Iranians had been testing their boundaries by violating the nuclear deal, and were now seeing how far they could push the Biden Administration. He noted an attack by Iranian-backed militias on Erbil in northern Iraq, in which a foreign contractor was killed and an American service member was injured, which carried “no consequences for Iran.”

“Next they will test existing sanctions and whether they will be enforced,” Goldberg predicted. “Unenforced sanctions are the same as lifting sanctions.”