Australia/Israel Review

Iran’s Korean Nuclear Backdoor

Mar 31, 2017 | Refael Ofek & Dany Shoham

Refael Ofek & Dany Shoham

This analysis argues that Iran is steadily making progress towards a nuclear weapon and is doing so via North Korea.

While the Vienna Nuclear Deal (VND) reached in 2015 is focused on preventing (or at least postponing) the development of nuclear weapons in Iran, its restrictions are looser with regard to related delivery systems (particularly nuclear-capable ballistic missiles) and to the transfer of nuclear technology by Iran to other countries. Moreover, almost no limits have been placed on the enhancement of Teheran’s military nuclear program outside Iran. North Korea arguably constitutes the ideal such location for Iran.

The nuclear and ballistic interfaces between the two countries are long-lasting, unique and intriguing. The principal difference between the countries is that while North Korea probably already possesses nuclear weapons, Iran aspires to acquire them but is subject to the VND. Iran has the ability, however, to contribute significantly to North Korea’s nuclear program, in terms of both technology (i.e. by upgrading gas centrifuges for uranium enrichment) and finance (and there is an irony in this, as it is thanks to its VND-spurred economic recovery that Iran is able to afford it).

This kind of strategic, military-technological collaboration is more than merely plausible. It is entirely possible, indeed likely, that such a collaboration is already underway.

This presumption assumes that Iran is unwilling to lose years to the freeze on its military nuclear program. It further assumes that North Korea is ready and able to furnish a route by which Iran can clandestinely circumvent the VND, thus allowing it to make concrete progress on its nuclear weapons program. And finally, it assumes that the ongoing, rather vague interface between the two countries reflects Iranian advances towards nuclear weapons.

A History of Collaboration

From the 1990s onward, dozens – perhaps hundreds – of North Korean scientists and technicians apparently worked in Iran in nuclear and ballistic facilities. Ballistic missile field tests were held in Iran, for instance near Qom, where the North Korean missiles Hwasong-6 (originally the Soviet Scud-C, which is designated in Iran as Shehab-2) and Nodong-1 (designated in Iran as Shehab-3) were tested. Moreover, in the mid-2000s, the Shehab-3 was tentatively adjusted by Kamran Daneshjoo, a top Iranian scientist, to carry a nuclear warhead.

Furthermore, calculations were made that were aimed at miniaturising a nuclear implosion device in order to fit its dimensions and weight to the specifications of the Shehab-3 re-entry vehicle. These, together with benchmark tests, were conducted in the highly classified facility of Parchin. Even more significantly, Iranian experts were present at Punggye-ri, the North Korean nuclear test site, when such tests were carried out in the 2000s.

Syria served concurrently as another important platform for Iran – until the destruction by Israel in 2007 of the plutonium-based nuclear reactor that had been constructed in Syria by Pyongyang. According to some reports, not only were the Iranians fully aware of that project in real time, but the project was heavily financed by Teheran. Considering Iranian interests, it was probably intended as a backup for the heavy-water plutonium production reactor of Iran’s military nuclear program, and possibly as an alternative to the Iranian uranium enrichment plant in Natanz in the event that it was dismantled.

While the Iranian heavy water plutonium production reactor differed from the North Korean gas-graphite reactor, the uranium enrichment routes of both countries are based on the gas centrifuge technique. In that respect, Iran seems to be ahead of North Korea, particularly in developing and manufacturing advanced centrifuges with carbon fibre rotors.

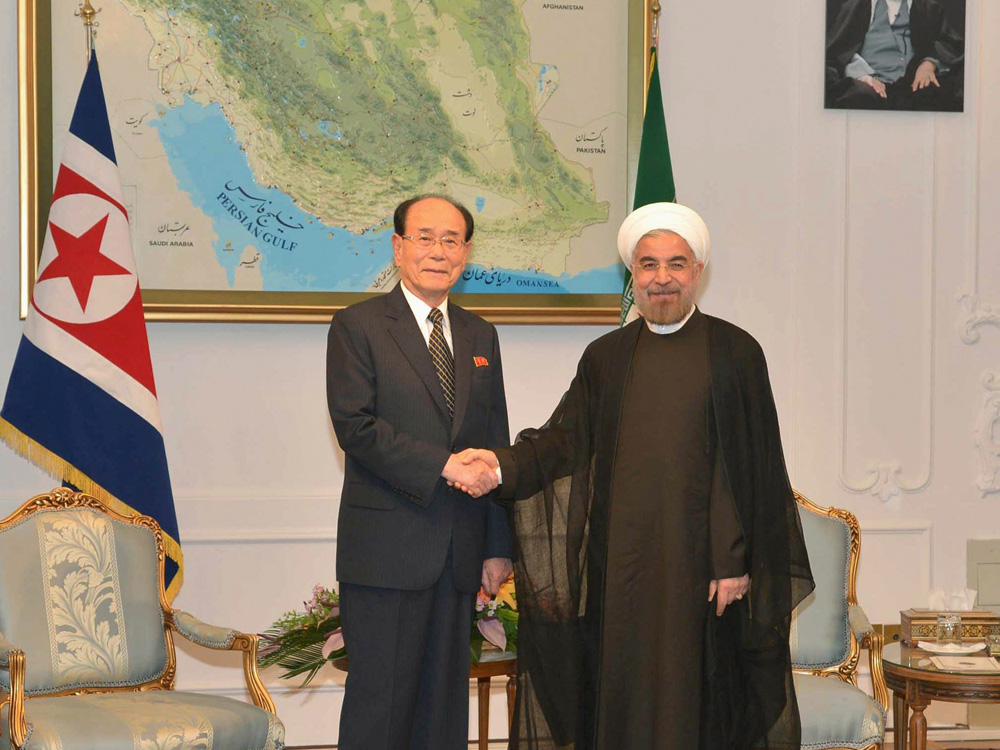

A Significant Agreement in 2012

A meaningful event took place in September 2012, when Daneshjoo, then the Iranian Minister of Science and Technology, signed an agreement with North Korea establishing formal cooperation. The agreement formally addressed such civil applications as “information technology, energy, environment, agriculture and food”. However, the memorandum of the agreement was ratified by Ali Akbar Salehi, head of the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran. Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei has since clarified that the agreement is an “outcome of the fact that Iran and North Korea have common enemies, because the arrogant powers do not accept independent states.” It is reasonable to infer that the agreement went far beyond its alleged civilian sphere.

The September 2012 agreement was probably intended to mask an evolving Iranian-North Korean cryptic interface, intended by Iran to compensate technologically for the following development: About two months earlier, President Obama had sent this secret message to Iran’s leaders: “We are prepared to open a direct channel to resolve the nuclear agreement if you are prepared to do the same thing and authorise it at the highest levels and engage in a serious discussion on these issues.” This message paved the way towards talks that started in Kazakhstan in February 2013, continued through the November 2013 Geneva and March 2015 Lausanne interim “framework” agreements, and culminated in the VND. The final agreement involved freezing substantial portions of Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for decreased economic sanctions on Iran.

In tandem with the 2012-13 events, a permanent offshoot of Iranian missile experts was established in North Korea that supported the successful field test of a long-range ballistic missile in December 2012. Iran and North Korea upgraded the Shehab-3/Nodong-1 liquid-fuelled missiles in a quite similar (though not identical) fashion, with Iran producing the Ghadr (range 1,600 km) and Emad (range 1,700 km) derivatives. In addition, components of the liquid-fuelled missile Musudan (also called the BM-25), which has a range of 2,500-4,000 km and was successfully field-tested in North Korea in 2016, have been supplied to Iran in the past by Pyongyang. The more advanced solid-fuel technology, which included the North Korean KN-11 submarine-launched ballistic missile and the Iranian Sajjil missile (range 2,000 km), was apparently developed collaboratively by the two countries. Also, a new North Korean ballistic missile test site was revealed in 2016 in Guemchang-ri – and it closely resembles the Iranian ballistic missile test site near Tabriz.

A delegation of Iranian nuclear experts headed by Mohsen Fakhrizadeh-Mahabadi, Director of the Iranian nuclear weapons project, was covertly present at the third North Korean nuclear test in February 2013. This test was apparently based – unlike the previous plutonium-core-based field tests – on an HEU (highly enriched uranium) core nuclear device (as, presumably, were the fourth and fifth nuclear tests, which took place in 2016). In 2015, information exchanges and reciprocal delegation visits reportedly took place, aimed at the planning of nuclear warheads. These include four North Korean delegations that visited Iran up until June 2015, one month before the VND was completed. It may be noted that in August 2015, a new gas centrifuge hall apparently became operational in North Korea’s main uranium enrichment facility.

Finally, in April 2016, a remarkable clash arose between US Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA) during a US House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing. They locked horns over planes that fly between Iran and North Korea, which should land and be rigorously inspected in China so as to prevent proliferation of North Korean nuclear and missile technology, let alone actual nuclear weapons, to Iran. Sherman charged that this had not been handled with sufficient care by the Obama Administration.

Beyond Coincidence

All in all, a major consequence of the VND is that the Obama Administration shot the US in the foot. It is expected that the terms of the VND and the abundance of money transacted as a result with Iran – about US$150 billion – will substantially facilitate the advancement of the nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs of both Iran and North Korea.

The chronology, contents and features of the overt interface between Iran and North Korea mark an ongoing evolutionary process in terms of weapons technologies at the highest strategic level. The two countries have followed fairly similar nuclear and ballistic courses, with considerable, largely intended, reciprocal technological complementarities. The numerous technological common denominators that underlie the nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs of Iran and North Korea cannot be regarded as coincidental. Rather, they likely indicate – in conjunction with geopolitical and economic drives – a much broader degree of undisclosed interaction between Teheran and Pyongyang.

The current Iranian-North Korean interface, which appears to be fully active, presumably serves as a productive substitute for the Iranian activities prohibited by the VND. It enables Iran, in other words, to continue its pursuit of nuclear weapons.

If not strictly monitored by the Western intelligence communities, this cooperation might take the shape of conveyance from North Korea to Iran of weapons-grade fissile material, weaponry components, or, in a worst-case scenario, completed nuclear weapons. To an appreciable degree, Iran is simultaneously assisting in the upgrading of North Korean strategic capacities as well.

The Trump Administration would be well advised to meticulously and rigidly ascertain that such developments do not take place.

Lt. Col. (ret.) Dr. Refael Ofek, an expert in the field of nuclear physics and technology, served as a senior analyst in the Israeli intelligence community. Lt. Col. (ret.) Dr. Dany Shoham, an expert in the field of weapons of mass destruction, served as a senior intelligence analyst in the Israel Defence Forces. Reprinted from Perspective Papers published by the Begin-Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies (BESA) at Bar-Ilan University. © BESA Centre, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Asia, Iran, North Korea