Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Words that Matter

Sep 18, 2015 | Ben Cohen

Iran, Israel and the “domestic consumption” myth

Ben Cohen

At the height of negotiations with the Iranian regime over its nuclear program, Western advocates of a deal found themselves rationalising the Islamic Republic’s uncompromising belligerence towards Israel. They did so as part of their bid to persuade a sceptical public that the mullahs would honour their agreements. Thus was born the “domestic consumption” theory of Iran’s internal politics, advanced by, among others, US Secretary of State John Kerry.

In a conversation with The Atlantic, Kerry acknowledged Iran’s “fundamental ideological confrontation” with Israel, but wondered aloud whether the regime was materially committed to the goal of eliminating the Jewish state. One month after the signing of the Iran nuclear deal, UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond made a similar observation on a visit to Teheran for the reopening of the British Embassy. “We’ve got to distinguish between revolutionary sloganising and what Iran actually does in the conduct of its foreign policy,” Hammond told the BBC. “We’ve got to, as we do with quite a number of countries, distinguish the internal political consumption rhetoric from the reality of the way they conduct their foreign policy.”

Actually, nothing in the present conduct of Iranian foreign policy – which, in its immediate neighbourhood, involves a destabilisation strategy based upon support for proxy terrorist groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon – suggests that the Islamist regime is becoming less revolutionary or, in Hammond’s phrase, “more nuanced”.

Just as puzzling is the idea that while there is now an expectancy in Western societies that politicians will be held to account for everything they say as well as do, the bellicose threats of Iranian leaders should, by contrast, be ignored. The implication is that Teheran’s leaders, in threatening Israel’s very existence, are catering to a domestic desire to hear such rhetoric. This assumes that erasing Israel from the map is a bigger priority for ordinary Iranians than rescuing their economy or bolstering the miserably poor levels of political freedom they currently enjoy.

Most importantly, the domestic consumption theory elides the revolutionary Islamist identity that has defined the Iranian state since the overthrow of the Shah in 1979. Yet it is precisely this identity that should stop us from treating Iran as just another country. What distinguishes revolutionary states is the belief that history is leading us to a pre-ordained outcome. In Iran’s case, this is a transcendent Islamic state grounded in sharia law. In an Islamic state, there is no place for such liberal indulgences as women’s rights or a free press. And above all, there is no place for a Jewish state, which is regarded as the primary source of oppression and injustice in the world.

One of the constants of the Iranian revolution has been its eliminationist rhetoric toward Israel, which has continued unabated in the wake of the nuclear deal. On August 25, the unfortunate Hammond had the rug snatched out from under his “more nuanced” comment by Hussein Sheikholeslam, who is the foreign affairs adviser to Ali Larijani, a former nuclear negotiator and the current speaker of the Iranian parliament. (In 2009, Larijani openly defended his country’s state doctrine of Holocaust denial before a stunned audience at the annual Munich Security Conference, which included Germany’s foreign minister.) “Our positions against the usurper Zionist regime have not changed at all,” Sheikholeslam declared. “Israel should be annihilated and this is our ultimate slogan.”

There are two ways to interpret this comment. One is the domestic consumption theory, which holds that such fulminations are intended to reassure a domestic audience that Iran will not waver on matters of fundamental principle. The other is to accept these statements at face value; in particular, Sheikholeslam’s assertion that the goal of annihilating Israel is “our ultimate slogan.”

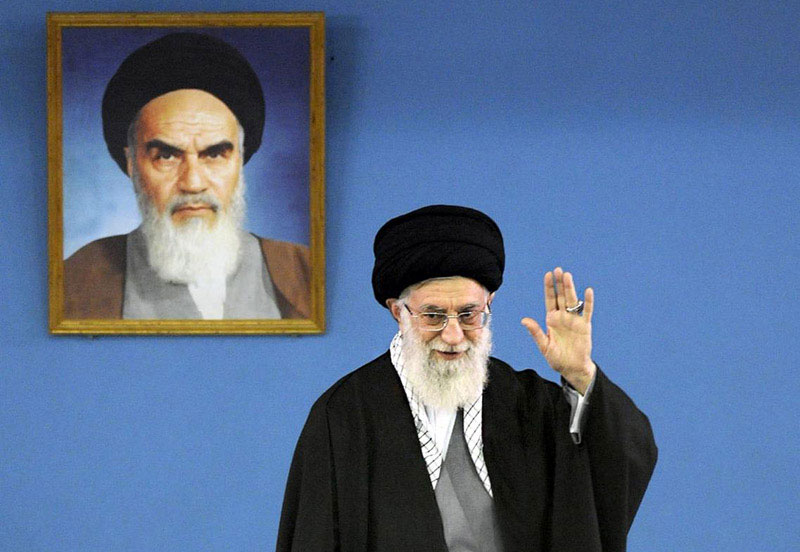

“Ultimate” is the operative word. “We should not be satisfied with what we have [the Islamic Revolution] within our borders; we should not think we are done,” declared Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in a Qods (Jerusalem) Day speech. “As long as this stinking wound and infected gland called ‘the Israeli Government’ is in the heart of Islamic territories, we cannot feel we have won.”

This speech is one of many pontifications on the subject of Zionist ignominy collected in Palestine, a 416-page book issued by Khamenei shortly after Secretary Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif shook hands over the nuclear deal. The shrillness of its rhetoric is closely modeled on the ravings of Nazi leaders like Hitler, Goebbels, and Julius Streicher, replete with the gruesome imagery of bodily infection and the odor of decay. Behind it, however, lies the core mission of Iran’s Islamic Revolution.

Over and over again, Khamenei’s writings and speeches underline the centrality of defeating Zionism to the Islamic Revolution. “Palestine is the most important issue in the Islamic world. No other international issue is more important than Palestine in the world of Islam,” he told an audience at the shrine of the Islamic Republic’s founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

“The reason is that the occupation of Palestine and Qods, which are parts of the body of Islam, is the source of all the weaknesses and problems in the Islamic world. This painful wound on the body of Islamic society is annoying the heart of the prophet. The heart and soul of the prophet in paradise is full of sadness. What is the solution, then? Jihad is the answer.”

“Palestine is not a strategic but a belief issue,” said Khamenei in another address. “It is about a heart connection. It is a religious issue.” And again, “Without winning the battle of Palestine, our victory is incomplete. Since the first days of his mission and struggle in Iran, our deceased great imam [Khomeini] gave the first priority to the issue of Palestine.” And again,

“Israel is a malignant cancer gland that needs to be uprooted. In contrast to what shallow people believe, it is not impossible to defeat Israel and the United States. Superpowers have come and gone throughout history. Materialistic powers are neither everlasting nor infinite. Yesterday, there was a power called the Soviet Union. It was one of the superpowers, but it no longer exists. A similar historical contemporary [sic] change is still before us.”

It takes a distinctively unimaginative mind to dismiss all this as “sloganising.” What is being articulated here is a non-negotiable doctrine. To accept Israel would be to wilfully abandon the very purpose of the Islamic Republic, to negate the essence of the Islamic revolution. Moreover, the real target is not the government of Israel, nor the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, nor even the State of Israel. In the final analysis, Iran’s Islamist rulers are at war with the Jewish people, and have been for nearly a century.

The echoes of Nazism in Khamenei’s rants are not a coincidence. As the German scholar Matthias Kuentzel explains in his fascinating Germany and Iran: From the Aryan Axis to the Nuclear Threshold, a long-standing “Germanophilia” among Iranians presented the Nazis with a ready audience for their propaganda, which stressed the common racial origins of Aryans and the majority population of Iran (“the land of the Aryans”). Its clearest expression took shape in the Persian-language broadcasts of Radio Zeesen, named after the small town south of Berlin where its offices were located.

In addition to the shared Aryanism myth, other core themes revolved around the symbiosis between antisemitism and anti-Americanism. “Every American who comes to the Orient does so on the instructions of the Jews,” Fritz Grobba, Hitler’s ambassador in Iraq – who played a major role in inciting the June 1941 Farhud pogrom against the Jews of Baghdad – told Radio Zeesen’s large audience. “The Jews are pulling the American strings.”

While eyewitness reports of crowds in bazaars, town squares, and coffee houses hunched over wireless sets attest to Radio Zeesen’s popularity, one listener was able to tune in privately, using a trusty, British-made Pye radio. That individual was Ayatollah Khomeini, who returned to the Shi’ite holy city of Qom in 1936 at the beginning of his long march to the leadership of the Islamic Republic that emerged from revolutionary turmoil 43 years later.

Khomeini, says Kuentzel, was a “connoisseur” of European antisemitism whose own writings betray the strong influence of Nazi doctrine on the “Jewish Question.” For example, in his key tract, The Islamic State, Khomeini wrote contemptuously of the “Jews” and their ambition for a “Jewish world state… And since they are liars and determined, I fear that they – God preserve us! – will one day achieve their goal.”

The Muslim Brotherhood, itself a firm Nazi ally, was another critical influence on the development of Khomeini’s ideas. Introduced to the Brotherhood by Navvab Safavi, the father of Islamism in Iran, Khomeini was attracted by its fervent antisemitism and hostility to the United States, as well as its rejection of Western cultural mores. Echoing similar emotions expressed by Sayyid Qutb, the Brotherhood’s leading exponent, Safavi lamented, in ironically sensual language, that “flames of passion rise from the naked bodies of immoral women and burn humanity into ashes.” For the austere Khomeini, this was music to the ears of one who described music as “treason to our nation.”

Following World War II, Khomeini became a leading member of the Fedayan-e Islam, an Iranian Shi’ite movement parallel to the Arab and Sunni Muslim Brotherhood. His political activity was uncompromisingly sectarian and focused on destabilisation. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Fedayan terrorists were responsible for assassinations and violence targeting the Shah’s officials. As Kuentzel points out, an oft-forgotten fact concerns Khomeini and the Fedayan’s active role in violently undermining the nationalist government of Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, whose removal in a coup in 1953 is routinely portrayed as the sole responsibility of the CIA.

Above all, Khomeini espoused an undisguised antisemitism that targeted Jews before Zionism or Israel. In June 1963, he addressed a crowd of 10,000 in Qom, where he taunted the Shah and his hated secret police, the SAVAK. “Why does SAVAK say that we should not speak of the Shah and Israel?” said Khomeini. “Does SAVAK mean that the Shah is an Israeli? Does the SAVAK consider the Shah to be a Jew?” Khomeini, certainly, considered the Shah to be a Jew.

As Kuentzel argues, the Ayatollah’s comments again displayed the influence of Qutb, who portrayed secular Muslim leaders, like Egypt’s Ali Pasha and Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, as “crypto-Jews.” He also quotes the observation of Khomeini’s biographer, Amir Taheri, that the notion of an international Jewish conspiracy lay at the heart of the Ayatollah’s worldview. This provided Khomeini with the basis of his attacks on the Shah, whom he described in a 1978 speech as a “Jewish agent” and “American snake.”

Khomeini’s antisemitism, which combined elements of Shi’a theology with the lexicon of European Jew-hatred, remains at the centre of the Islamic Republic’s ideology today. In other words, Khamenei’s Palestine, along with his speeches attacking the Jews, their state, and their history, is not simply a hangover from a revolutionary tradition that has been tamed by so-called “moderate” clerics. Instead, it is what defines the Islamic Republic’s approach to foreign affairs.

Moreover, when compared with the experiences of other authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, the “domestic consumption” excuse for Iranian antisemitism carries little weight. For Iran to abandon antisemitism, the regime would first have to reckon with Khomeini’s legacy, rather as the Soviet Union did with Josef Stalin following his death in 1953. It took three years for Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, to appraise Stalin’s crimes, and then only cautiously, in the form of a “secret speech” to the Communist Party’s 20th Congress in 1956. For Iran, even this would be going too far. None of Iran’s clerics have denounced Khomeini’s internal campaign of repression and murder of opponents, much less his antisemitism. There are no indications that they ever will, despite the wishful thinking of Western politicians in the weeks that have passed since the nuclear deal was signed.

In other ways, Iran’s view of the Jews mirrors that of Muammar Gaddafi, the late Libyan dictator who was overthrown in 2011. Gaddafi shared many things with the Iranians: A belief that his “Jamahiriya” form of government was historically destined to supplant other forms of political rule; a foreign policy grounded on financial and military support for terrorist groups; and a state doctrine of Holocaust denial.

Significantly, when Khamenei shared his reflections on Gaddafi in 2012, he expressed amazement that “this gentleman wrapped up all his nuclear facilities, packed them on a ship and delivered them to the West and said, ‘Take them!'” He added, “Look where we are, and in what position they are now.” In other words, Gaddafi’s historic error was to espouse the revolution while abandoning the means to carry it out. Khomeini would certainly not have agreed to such an undertaking, and we can be sure that Khamenei will not do so either.

What, then, can we conclude? First, that Iran does not perceive its enmity towards Israel as an inter-state conflict – only Western politicians and diplomats see it that way – but as a battle against an adversary that dates back to the days of the Prophet Muhammad. In that regard, asking or expecting Iran to recognise Israel is an absurdity; it would be the equivalent of demanding that the Iranians eschew the entire Islamic revolution. The integrity and purpose of Khomeini’s revolution, and not the fantasy of “domestic consumption”, is what explains the continuing stream of antisemitic, eliminationist rhetoric from Teheran. It will end only when the regime behind it is no more.

Ben Cohen is a Senior Editor at The Tower magazine and a New York-based writer on international affairs. © The Tower (www.thetower.org), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

This article is featured in this month’s Australia/Israel Review, which can be downloaded as a free App: see here for more details.

Tags: Antisemitism