Australia/Israel Review

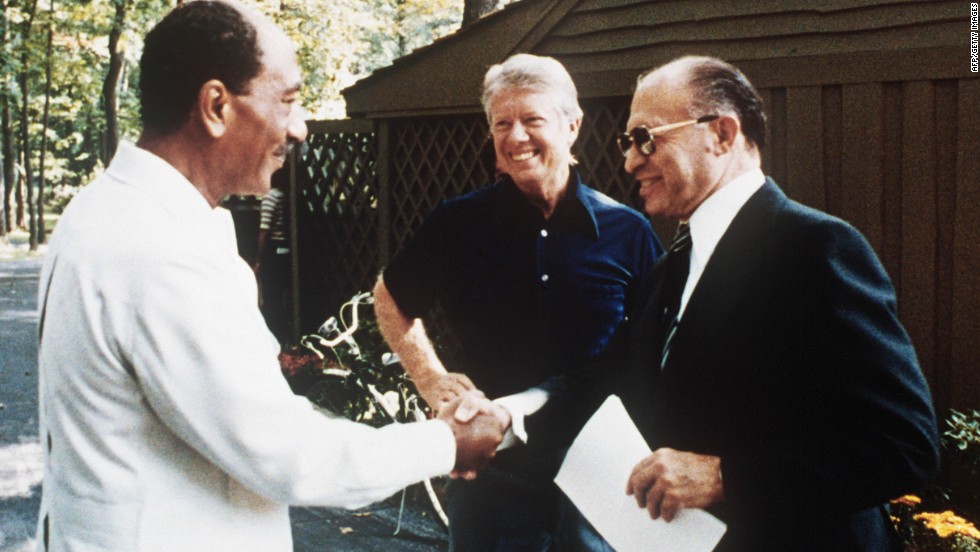

Essay: When Anwar met Menachem

Sep 4, 2018 | Amotz Asa-El

The Camp David Accords, 40 years on

Frustrated by Egyptian and Israeli negotiators’ wrangling over the fate of Yamit, a seaside Israeli town of 2,500 in the Sinai Desert planned to eventually include a seaport, an airport and 250,000 settlers, an American diplomat asked Moshe Dayan why Israel had built it in the first place.

“We never thought the Egyptians would make peace,” replied the then Foreign Minister who, as a general, had conquered the Sinai in 1956, and, as Defence Minister, had overseen its re-conquest in 1967.

The exchange took place during the intense Egyptian-Israeli peace talks at Camp David in September 1978, ten months after Anwar Sadat’s historic visit to the Jewish state. Forty years on, the accords produced during that 13-day summit shine as a ray of light in an otherwise turbulent Middle East.

The deal between Sadat and then Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin was simple in principle, but politically, diplomatically, logistically, and economically complex, and fraught with risk.

The principle was land for peace, as agreed already in a secret meeting in Morocco between Dayan and Egyptian deputy prime minister Hassan Tohami, two months before Sadat’s dramatic arrival in Israel in November 1977.

Mediated by US president Jimmy Carter, the deal boiled down to Egypt’s full recognition of Israel in return for Israel’s full relinquishment of the Sinai – which is more than twice the combined size of Israel, the West Bank, the Golan Heights and the Gaza Strip in land area.

Politically, the deal unsettled broad circles in both countries.

In Egypt, Foreign Minister Ismail Fahmi resigned following Sadat’s journey to Jerusalem, and Defence Minister Mohamed Gamasy was fired by Sadat the month after the Camp David summit, due to the former war hero’s criticism of the deal. Such opponents within the establishment were in addition to the Islamists outside it. For them, any such agreement with Israel was anathema, and four of them assassinated Sadat three years later.

All these tremors within Egypt came on top of the wrath Sadat courted in the Arab world where he was widely condemned as a traitor, with the Arab League expelling Egypt and relocating its headquarters from Cairo to Tunis.

In Israel, meanwhile, the country’s first peace deal was opposed by key members of Begin’s ruling Likud party, including Knesset speaker and future Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who abstained in the parliamentary vote ratifying the agreement, and future Defence Minister Moshe Arens, who voted against it.

Several other Likud lawmakers split away and formed a faction that opposed the peace agreement.

In the opposition, some Labor legislators also opposed the deal, most notably former Foreign Minister Yigal Allon, a war hero from the 1948 war. These secular opponents were joined by high profile rabbis and religious politicians, who would help lead the West Bank settlement project over the following decade.

Diplomatically, the deal was made more challenging by Sadat’s quest to avoid appearing as a betrayer of the broader Arab cause. That is why he demanded that the bilateral Israel-Egyptian agreement be linked to some kind of commitment to the Palestinians.

The Camp David Accords consequently contained a clause stating that Israel will grant autonomy to the West Bank and Gaza and recognise “the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.” This was the first official Israeli statement recognising the Palestinians as a nation rather than simply Jordanian and Egyptian citizens, as Jerusalem had previously argued.

Israel, for its part, demanded a significant diplomatic concession of its own, namely that the Sinai be demilitarised, and thus become a buffer between the Israeli and Egyptians armies – which had previously fought some of history’s bloodiest armour battles across three wars in the peninsula.

Logistically, the deal required the removal of Israel’s vast military deployment in the Sinai, which included some 500 tanks, thousands of troops, and four Israeli-built airports. In addition, Israel would have to evacuate some 5,000 civilians living in 18 settlements, from a string of Red Sea resort towns opposite Saudi Arabia to the oil-drilling town Shalhevet, opposite Africa, to the fishing village Nahal Yam on the Mediterranean coast, in addition to the larger town of Yamit.

Economically, Israel sought replacements for the airfields it would abandon and for the oil it had been extracting in the western Sinai.

The deal addressed all these demands and grievances.

Israel recognised the Palestinians’ nationhood and retrieved its military assets and civilians from the Sinai; Egypt agreed to demilitarise the Sinai, and to sell oil pumped from the Sinai to Israel for the following 15 years; while the US built new military airports in Israel’s Negev Desert to replace those it lost in the Sinai and created strategic warning stations east of the Suez Canal to detect any future invasion.

The Camp David Accords were, in short, a masterpiece of diplomatic balance, vision and sacrifice. Better yet, the deal actually worked, and still works, to this day.

The exchange of ambassadors between Cairo and Jerusalem in 1979 was followed by routine Israeli navigation through the Suez Canal. Indeed, in what previously seemed like science fiction, Israel Navy vessels came to habitually cross through that waterway over which, back in 1973, the Egyptian army had stormed the IDF’s fortified positions along the “Bar-Lev line”.

Egyptian and Israeli intelligence officers regularly exchange information concerning Islamist terrorist activity in the Sinai, while Egyptian officials regularly mediate between Israel and the Palestinians.

This August, for instance, the head of Egypt’s General Intelligence Service, Abbas Kamel, met Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and the heads of Israel’s National Security Council and Shin-Bet secret service to craft a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Personal relations between Netanyahu and Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi are believed to be warm.

Egyptian-Israeli peace has endured major turbulence, including Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and even more improbably, the incumbency of Islamist Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in 2012-2013. Egypt did withdraw its ambassador from Tel Aviv several times through the years, for instance in 2011 following a border incident in which three Egyptian soldiers were killed. However, diplomatic ties were never fully severed, and the ambassadors were always ultimately returned.

Indeed, in a Middle East beset by multiple civil wars and multilateral conflicts, Israeli-Egyptian relations have become an engine of pragmatism and stability.

Yes, the land-for-peace formula was later tested less successfully between Israel and the Palestinians. In the Egyptian-Israeli peace agreement, however, where the land at stake was mostly empty and the leaders on both sides of it proved both motivated and equipped to deliver concessions – the deal worked.

This is not to say relations are completely smooth sailing.

Most disappointingly from Israel’s point of view, the Egyptian media and cultural elite remain mostly hostile to the Jewish state, and antisemitic thinking and rhetoric are sadly common and legitimate in Egypt.

Less dramatically, but perhaps more tragically, Egypt has frustrated original Israeli hopes for a deep economic relationship.

Most memorably, Israeli businesswoman Dvora Ganani, who created a cosmetics import business in Cairo, was expelled in 1997, while Israeli Arab businessman Azzam Azzam, who recruited Egyptian subcontractors for an Israeli textiles firm, was arrested in 1996 for alleged espionage and jailed for eight years.

In the same spirit, Egypt effectively rejected the vision of a “New Middle East” with which Israel went to the 1993 Oslo Accords, and which advocated the removal of regional economic borders in the spirit of the European Union’s model.

Then again, when done through government auspices, business did develop between the two countries.

In 2004, Egypt signed a deal with Israel and the US that exempted Egyptian exports from US tariffs if they included a specific portion of Israeli-made components. The following year a deal was signed to sell Egyptian gas to the Jewish state.

Consequently, bilateral trade grew from less than US$50 million in 2003 to more than US$500 million by the time of Hosni Mubarak’s downfall in 2011.

Subsequent internal violence put an end to the flow of Egyptian gas to both Israel and Jordan, as terrorists repeatedly sabotaged the pipeline that ran through the Sinai. However, since then, Israel has found offshore gas in its Mediterranean waters, and last year the Israeli company Delek signed a deal with the Egyptian company Dolphinus to supply Egypt with US$15 billion worth of Israeli gas over 10 years.

Yes, Israeli-Egyptian relations have yet to constitute full peace, but 40 years after the Camp David turning point in 1978, they are light years away from the shadow of constant bloodshed where they began.