Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The Myths of 1953

Aug 10, 2017 | Ray Takeyh

What newly-published documents reveal about the CIA role in an Iranian coup

Ray Takeyh

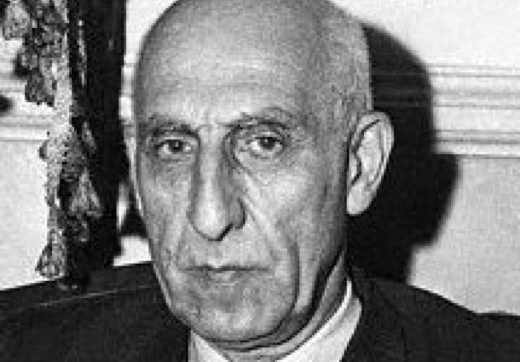

William Faulkner once mused that the past is never dead, in fact it’s not even past. The story of the coup that toppled Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq in 1953 may not be dead, but it is unhinged from history. Tall tales by a scion of the American establishment – former CIA agent and presidential grandson Kermit Roosevelt – and reams of studies by left-wing professors have sustained the myth that the Eisenhower Administration ousted Mossadeq. The Iranians are mere bystanders in this story, watching helplessly as a malevolent America manipulates their nation’s destiny. Most academic speculations remain cloistered in college campuses, but the myth of Mossadeq’s overthrow long escaped those boundaries.

In 2015, Barack Obama confided to Thomas Friedman, “if you look at Iranian history, the fact is that we had some involvement with overthrowing a democratically elected regime in Iran.” In her memoir Hard Choices, Hillary Clinton echoed this theme: “The country’s monarch, the Shah, owed his throne to a 1953 coup supported by the Eisenhower Administration against a democratically-elected government thought to be sympathetic to Communism.”

In June, the State Department finally released a cache of documents that John Kerry had embargoed as he pursued his arms control ambitions with Iran. Those sceptical of the standard account of the coup will find in the files more evidence that the mythmakers were wrong. It is hard to read these cables and come to the conclusion that America overthrew Mossadeq.

The proper place to begin is a brief recapitulation of the crisis. For decades, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) had exploited Iran’s oil, paying less revenue to Teheran than taxes to the British treasury. The rise of post-colonial nationalism in the aftermath of World War II made such anachronistic arrangements untenable. As the European empires crumbled, their assets became fair game for the newly independent nations. Mohammad Mossadeq was one of Iran’s more esteemed politicians, having fought his entire life for his country’s autonomy and dignity. As a parliamentarian, he spearheaded the nationalisation of Iran’s oil in 1951. Soon after the passage of the bill, the Shah had no choice but to promote its champion to the premiership. It is important to note that Mossadeq was a nationalist who once believed in constitutionalism and the rule of law. Had his career ended in parliament, he would be remembered as one of Persia’s greatest patriots. The tragedy of Mossadeq is that he became prime minister, a post unsuited to his temperament.

Mossadeq’s intransigence made a negotiated settlement nearly impossible. The Prime Minister and his allies dismissed compromises that would preserve any aspect of British power. As Mossadeq informed a startled American envoy, Henry Grady, “I assure you, Excellency, that we value independence more than economics.” In essence, Mossadeq saw the nationalisation as an act of liberation. Once diplomacy is infused with such evangelical spirit, technical agreements and profit-sharing schemes are overwhelmed by a cry for emancipation.

Even at the height of the Cold War, the Truman Administration played the role of an honest broker. This was not the first time that Harry Truman had saved Iran. In 1946, when Joseph Stalin planned to take over the northern Iranian province of Azerbaijan, it was Truman who rebuffed the Soviet dictator.

America’s stellar diplomats such as Dean Acheson and Averell Harriman devised innumerable schemes that conceded the principle of Iranian nationalisation while compensating Britain for its confiscated assets. It was Teheran, more than London, that brushed aside all such arrangements.

The pressure of governing during a time of crisis accentuated the darker shades of Mossadeq’s personality. The one-time champion of the rule of law now rigged elections and unleashed crowds to intimidate political opponents. Mossadeq’s most important target was the monarchy, an institution he relentlessly sought to hollow out. The Premier appreciated that to weaken the monarchy he had to wrestle away its control of the armed forces. He purged pro-Shah officers, sought to gain control of the Ministry of War, and even tried to prevent the monarch from having contact with his officers. In the oil negotiations, Mossadeq hardly took into account the Shah’s ideas and concerns.

Even before Western intelligence services devised plots against Mossadeq, his party, the National Front, started to crumble. The middle-class elements of the coalition, anxious about their declining economic fortunes, gradually looked for an alternative. The once-reliable intelligentsia and the professional classes were chafing under Mossadeq’s authoritarianism. A number of smaller political parties that had been associated with his movement were also contemplating their exit. Even more ominously, the armed forces, which had stayed quiet despite Mossadeq’s purges, grew vocal and began to participate in political intrigues.

Among Iran’s factions, the clergy would play the most curious role. The Islamic Republic has whitewashed the role that the mullahs played in Mossadeq’s downfall. The most esteemed Shi’ite cleric at that time, Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Hossein Borujerdi, initially supported the nationalisation act and encouraged the Shah to oppose Britain’s imperial designs. The National Front’s liberal disposition, however, unsettled the clerical order. At the outset of its rule, the party stood for redistributing land, female franchise and constructing a modern educational system. The oil crisis may have pushed aside such reformist tendencies but did not diminish clerical suspicion. As large landowners, the mullahs distrusted governments prone to carving out their property. As reactionaries, they disdained female equality in all its forms. And as guardians of tradition, they were averse to modernisation of Iran’s educational sector.

Still, it was the mayhem on the streets rather than the National Front’s legislative goals that most disturbed the clerical class in the summer of 1953. They feared that continuing disorder would empower the Communist Tudeh party and might even lead to displacement of the monarchy by a radical leftist regime. The clerical oligarchs were comfortable with the deferential Shah and soon began to shift their allegiances. The rabble-rouser Ayatollah Abdel Qassem Kashani might have led the charge against Mossadeq from his perch as the Speaker of the Parliament, but behind him stood a clerical cohort antagonistic to the Prime Minister.

By 1953, America had a new President, the victor of the Second World War, Dwight Eisenhower. Despite perceptions that he was a trigger-happy cold warrior, Eisenhower appreciated the arrival of Third World nationalism as a force in global politics and he was sophisticated enough to recognise the difference between neutrality and communism. Given the gravity of the situation, he soon grew concerned that Mossadeq’s unfolding dictatorship of the left could easily slide into Communist rule. Mossadeq had rejected a string of settlement proposals and was not even superficially interested in negotiations. In the meantime, Iran’s domestic stability continued to deteriorate.

The recently released documents highlight the dilemmas that Eisenhower faced in Iran. America’s formidable Ambassador Loy Henderson warned the White House; “During [the] last six months there has been sharp shift in basis [of] Mossadeq support among political leaders. Most elements [of the] original National [Front] movement now (repeat now) [are] in open or tacit opposition.” Henderson noted that Mossadeq’s “frequent use of mass demonstrations in order [to] bring pressure on opposition, his inability [to] obtain [the] cooperation [of] outstanding political leaders [of the] country, and his resort [to] military law [to] maintain order have served [to] weaken his popularity even among [the] masses.”

It was hard to see how Eisenhower could take advantage of Mossadeq’s mishaps, however, when he was informed by his intelligence services that the “CIA presently has no group which would be effective in spreading anti-Mossadeq mass propaganda” and the “CIA has no group in Iran which could effectively promote riots demonstrating against Mossadeq.” In the fabled history of the coup, from such incapacity the CIA developed a resilient network that easily toppled a popular leader a few months later.

The idea of a coup was relentlessly promoted by aggrieved Iranian politicians who believed that Mossadeq’s disastrous course was ill-serving their country. General Fazlullah Zahedi, a distinguished soldier and one-time member of Mossadeq’s cabinet, became the focal point of resistance. Zahedi confirmed the Embassy’s view that a nascent anti-Mossadeq coalition already existed and could gain power with limited American support. It was the Iranians, more than the CIA, who initially offered Eisenhower a path out of his predicament.

The newly declassified documents shed much light on the role that the clergy played. Most scholars of the coup have long acknowledged that Kashani was involved in opposition activities. Given his reputation for self-promotion and corruption, however, it was easy to cordon off the disreputable Kashani from the seminaries. Borujerdi’s public silence is seen as an indication that the venerable Shi’ite cleric disapproved of the plots against Mossadeq.

In an intriguing cable, the CIA noted that Zahedi reported that “Kashani, Borujerdi and [Ayatollah Muhammad Reza] Behbahani were reaching an understanding on the need to bolster the Shah in resistance to Mossadeq.” The CIA station in Teheran similarly stated that when approached by two clerics serving as members of parliament (in Iran the body is called the Majlis), “Borujerdi is alleged to have instructed them to form a religious faction within the Majlis.” Far from being a passive observer, the priestly class seemed to have made its preferences clear.

By April, we see that the basic elements of the coup were in place largely independent of American participation. The CIA reported that “court representative attempted to enlist Mullah Kashani’s support of [a] plan.” The plan was essentially for the Shah to sack Mossadeq in favour of Zahedi. This was hardly an intricate plot, as the Shah had the authority to dismiss his premier, whose miscalculations had already eroded his popular standing. The street power of the mullahs could also be used, as the mosque could mobilise a crowd on short notice. The problem that the plotters confronted was that the Shah was a weak and indecisive person who wanted Mossadeq ousted without his active participation.

The Iranian planning and pleading finally pressed Washington to be more directly involved in the plot to unseat Mossadeq. Roosevelt went to Iran to oversee the operation, code-named the TPAJAX Project or Operation Ajax. The scheme concocted with the participation of Britain’s MI6 rested on the Shah dismissing his prime minister. A series of emissaries, including the Shah’s feisty sister, were smuggled into the palace to stiffen up the diffident monarch. A crude propaganda campaign was also launched that absurdly accused Mossadeq of being of Jewish ancestry. The CIA would seek to rekindle Britain’s network of agents to instigate crowds – only to realise that London had overstated their value. Zahedi emerged as the centrepiece of the campaign, given his stature in the armed forces.

The coup was finally launched on August 13, when the Shah issued a decree dismissing his premier. It was an inauspicious start, as the day before the coup, the National Intelligence Estimate, expressing the collective judgment of all US spy agencies, proclaimed, “As a general proposition, we believe that the odds still favor Mossadeq’s retention of power at least through 1953.” Mossadeq seemed to have been tipped off about the Shah’s decision and quickly arrested the officer dispatched to dismiss him. The Shah, true to form, fled the country. It is important to stress that the Prime Minister’s defiance of the Shah’s decree was unconstitutional. The many defenders of Mossadeq’s “democratically elected” government rarely mention that his continuation in power at this point was illegal.

After the failure of the coup, a mood of resignation descended on Washington. The State Department acknowledged that the “operation has been tried and failed.” The CIA warned its station in Iran that “we should not participate in any operation against Mossadeq which could be traced back to US and further compromise our relations with him which may become [the] only course of action left open to US.”

Eisenhower’s close aide and confidant, the crusty General Walter Bedell Smith who had been Director of Central Intelligence until becoming under-Secretary of State in February 1953, had the unenviable task of apprising his boss. He summed up the evaluation of all the relevant agencies and told a glum President that “the move failed… We now have to take a whole new look at the Iranian situation and probably have to snuggle up to Mossadeq, if we’re going to save anything there.” Among the newly released documents is an after-action assessment by the CIA’s Office of National Estimates that stressed, “Mossadeq’s numerous non-Communist opponents have been dealt an almost crippling blow and may never again be in a position to make a serious attempt to overthrow him.” For the United States, the coup was over.

The purveyors of the traditional narrative of the coup chose to ignore all this and insist that despite the sour mood in Washington, Kermit Roosevelt persisted and eventually succeeded in overthrowing Mossadeq. This account is based largely on Roosevelt’s sensationalist book, Countercoup: The Struggle for Control of Iran. But the book is the product of Roosevelt’s exaggerated imagination and does much to embellish his role at the expense of describing the actual course of events. The fact is that the second – successful – coup was largely an Iranian initiative. The CIA station in Iran continued its reporting activities and was involved in disseminating the Shah’s decree dismissing Mossadeq. But it is hardly a nefarious act to publicise a legal ruling by a monarch discharging his prime minister.

In the chaotic and confused atmosphere of Teheran, political fortunes swiftly changed. By August 19, the second coup began. Zahedi continued to keep in touch with the military contingents under his command and sought to bring in additional army units from surrounding areas. The street protests persisted, some instigated by Kashani and the mullahs while others generated spontaneously. The Tudeh (Communist party) seemed to have overplayed its hand, as its cadre took to the streets waving Communist banners and calling for “people’s democracy”. As the events rapidly unfolded, the CIA station reported that the “Army [is] still basically [with the] Shah” and “Religious leaders now desperate. Will attempt anything. Will try [to] save Islam and Shah of Iran.” Far from being in command of the situation, the agency’s representatives in Teheran cabled that as of August 13, “CIA cut out of military preparations by [General Nader] Batmangeliche and Zahedi.”

Despite his usurpations of power, Mossadeq remained a man of his class and was disturbed by the violence engulfing the cities. The military that was dispatched to suppress the riots was still the Shah’s army. Once the armed contingents entered Teheran, they quickly turned their focus on government offices and eventually the prime minister’s residence. Zahedi and his men had planned well and were in position to take over key facilities with dispatch. Mossadeq was too much of an aristocrat to spend his life in hideaways and soon surrendered to Zahedi’s forces.

In Washington, the shock of the royalist restoration triggered calls for reports from the local officials. Ambassador Henderson, in his role as the United States’ chief representative in Iran, informed the White House that the protesters “seemed to come from all classes of people including workers, clerks, shopkeepers, students, et cetera.” This stands in stark contrast to professors and pundits who insist that the demonstrations were mere collections of thugs paid by the CIA and its accomplices. For his part, Henderson noticed that “not only members [of] Mossadeq’s regime but also pro-Shah supporters [were] amazed at the latter’s comparatively speedy and easy initial victory which was achieved with high degree of spontaneity.” It seems that the Iranian public had grown weary of Mossadeq’s inability to resolve the oil crisis and his persistent power-grabs.

The newly declassified documents do much to undermine Roosevelt’s later tales. The CIA station in Teheran echoed Henderson’s assessment and noted, “The Royalist, pro-Zahedi movement of August 19th contained a large element of spontaneity and there seemed to have been a genuine reaction of shock and dismay on part of the Tehran populace when the Shah left Iran for Iraq.” Armed with the judgment of his field agents, CIA acting Director Charles Cabell – Allen Dulles was on vacation and did not see a reason to disrupt his holiday and return to Washington – informed Eisenhower that “an unexpected strong upsurge of popular and military reaction to Prime Minister Mossadeq’s government has resulted according to late dispatches from Tehran in the virtual occupation of that city by forces proclaiming their loyalty to the Shah, and to his appointed Prime Minister Zahedi.” Although the official documents do not record the President’s reaction, Eisenhower must have smiled at his unexpectedly good fortune.

In August 1953, the Iranians reclaimed their nation and ousted a premier who had generated too many crises that he could not resolve. The institution of the monarchy was still held in esteem by a large swath of the public. And the Shah commanded the support of all the relevant classes, such as the military and the clergy. Mossadeq’s unpopularity and penchant toward arbitrary rule had left him isolated and vulnerable to a popular revolt. America might have been involved in the first coup attempt that failed, but it was largely a bystander in the more consequential second one. Although Kermit Roosevelt would go on to inflate his role, other American diplomats and spies should be credited for the integrity of their reports and the acknowledgment of their own surprise at the turn of events.

It is unlikely that the professoriate and the left will abandon their myths about 1953. They are too invested in their narrative and too obsessed with defending the Islamic Republic to defer to history’s judgment. The clerical complicity in the demise of Mossadeq is sure to embarrass the theocratic regime that has gained much from Roosevelt’s legendary story. But for those with an open mind, the case is now closed.

Ray Takeyh is Hasib J. Sabbagh senior fellow at the US Council on Foreign Relations. © Weekly Standard (www.weeklystandard.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iran