Australia/Israel Review

China goes to the Middle East

Feb 3, 2016 | Michael Singh

Michael Singh

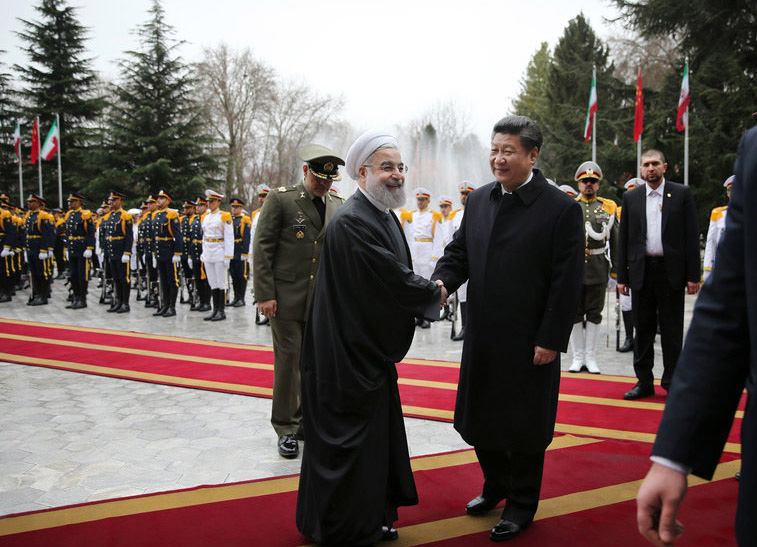

Even as the Iran nuclear deal and the potential for rapprochement between Teheran and the West have inspired countless op-eds, China’s budding relationship with Iran has gone relatively unremarked upon. But on Jan. 23, Chinese President Xi Jinping became the first world leader to visit Iran after the deal. Xi stated that he sought to open a “new chapter” in China’s relations with Iran. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said, “The Islamic Republic will never forget China’s cooperation during [the] sanctions era.”

Xi’s trip to the region, which also included stops in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, was a continuation of Beijing’s increased involvement in the Middle East. It may be less dramatic than other great powers’ forays into the region (Russia’s recent intervention in Syria, for one), but it is no less significant. It signals that Washington’s decades-long period of unchallenged pre-eminence in the Middle East is drawing to a close.

China’s commercial ambitions in the Middle East are expanding. As the United States becomes increasingly energy self-sufficient, China has moved in the opposite direction. It is projected to overtake the United States as the world’s largest energy consumer by 2030, as its demand for imported oil grows from six million barrels per day to 13 million by 2035. The bulk of its new supply is likely to come from the Middle East, which China also needs for tapping new markets to produce its goods, invest its capital, and secure new labour. It is in this context that China has articulated its Middle East strategy, focusing on areas like energy cooperation and infrastructure investment. It has sought to integrate the region into its One Belt, One Road initiative, which Xi announced in 2013 and which would connect China with Eurasia.

However, China’s expanding economic interests create strategic vulnerabilities, which have increasingly drawn Beijing into the region diplomatically and militarily. For example, the country’s involvement in the Iran nuclear talks increased partly because of its mounting concern that a US-Iranian or Israeli-Iranian conflict could endanger oil exports through the Strait of Hormuz. Fifty-two percent of China’s oil imports come from the Gulf region. China has recently, on several occasions, hosted representatives of opposing Syrian factions. In 2013, it even took a stab at an Israeli-Palestinian peace plan during separate visits by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian Authority leader Mahmoud Abbas. In all cases, however, China did not deviate from conventional policy approaches but instead used the opportunities to showcase its growing regional and global clout.

In addition, China has begun deploying its military more frequently in the region. For example, in May 2015, China announced that it would hold naval exercises with Russia in the Mediterranean. Chinese fighter jets have also refuelled in Iran, the first foreign military units permitted on Iranian soil since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Chinese warships have made port calls in both Iran and the United Arab Emirates.

Conflicts in Iraq, Libya, and Yemen have threatened Chinese workers who are engaged in infrastructure, energy, and other projects in the region. In 2011, China was forced to evacuate 35,000 Chinese nationals from Libya when the country dissolved into civil war. It was the Chinese navy’s most sophisticated and longest-range operation to date. And its success rested on the fact that its vessels were already stationed in the Gulf of Aden on a counter-piracy mission. That experience most likely underscored for Chinese leaders the value of forward-deployed naval assets and added momentum to Beijing’s drive to build a naval facility in Djibouti – its first overseas base.

Despite its deepening involvement in the region, China has so far sought to avoid taking sides in the Middle Eastern conflicts. It has pulled off the improbable feat of cultivating close ties with Israel, the Arab countries, and Iran all at the same time. For these states, good relations with Beijing bring not only trade and investment but also military technology (though inferior to American materiel) without the political strings. When Washington hesitated to sell armed drones to the United Arab Emirates, China offered its lower-priced Predator knockoff, the Wing Loong.

In the long run, however, China’s impartiality will be difficult to sustain as the region grows increasingly polarised. Already, China has struggled to respond to crises that pit its allies against one another. Beijing reportedly offered arms to the former Libyan leader Muammar al-Qaddafi even as it declined to block a UN Security Council resolution that permitted international air strikes in Libya, partly in deference to the wishes of the Arab states. It reached out to Hamas in the Gaza Strip despite its friendship with Israel and wariness of Islam. And Xi reportedly angered Saudi Arabia when he cancelled his first scheduled trip to Riyadh after war broke out in Yemen. Xi likely feared that his visit would make him appear partial to the Saudis and anger Iran. Eventually, such zigzagging has to cross someone.

If Beijing is eventually forced to pick one key ally, it will most likely choose Iran. Teheran, by itself, presents significant strategic opportunities for China. It can help mitigate China’s energy security concerns by virtue of its position on the Strait of Hormuz – otherwise dominated by US allies – and has potential to offer China routes for pipelines through Central Asia.

Iran also offers China the prospect of deeper regional security. Iran shares Beijing’s desire to reshape the international order by minimising US dominance. Even though the Arab states and Israel welcome China’s overtures as a way to increase their leverage with Washington, they are nearly unanimous in their desire for greater, not diminished, US leadership.

In confronting China’s Middle East strategy, the United States does not need to take a zero-sum approach. To an extent, their interests there – including the free flow of commerce and in countering terrorism – overlap.

Nevertheless, any basis for cooperation will be undermined if China repeats its past practice of sending sensitive nuclear technology to Iran, or if it transfers considerable expertise in defensive weaponry, such as ballistic missiles and counter-maritime and air systems.

As China steps up its involvement in the Middle East, the United States should continue pressuring Beijing to honour the Iran nuclear deal and the remaining sanctions, and it should urge its allies, particularly the Gulf Cooperation Council member states, and others concerned about Iran’s empowerment, to deliver the same message.

In the past, Washington has imposed sanctions on Chinese entities and delivered strong diplomatic messages to compel Beijing to comply with the sanctions on Iran. But the message will have a stronger impact if amplified by other countries that China is courting.

At the same time, Washington should step up its own engagement with Beijing on regional issues and seek to channel Chinese activities into established multilateral mechanisms, along the lines of the Iran talks and ongoing counter-piracy missions.

As its flat-footed response to Russia’s Syria adventure reveals, the United States has little experience in dealing with other powers involved in the Middle East. It is vital that Washington gets a grip on how to approach China’s growing presence in the region, as these first steps will set the stage for how the world’s two great powers clash and collaborate over this troubled region.

Michael Singh is the Lane-Swig Senior Fellow and managing director at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. This article was originally published on the Foreign Affairs website. © 2016 Council on Foreign Relations, publisher of Foreign Affairs. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency.

Tags: China