Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: A Return to Zion

Nov 7, 2018 | Jay Lefkowitz

The Zionist Ideas: Visions for the Jewish Homeland – Then, Now, Tomorrow

Gil Troy, The Jewish Publication Society, April 2018, 608pp., US$71.99

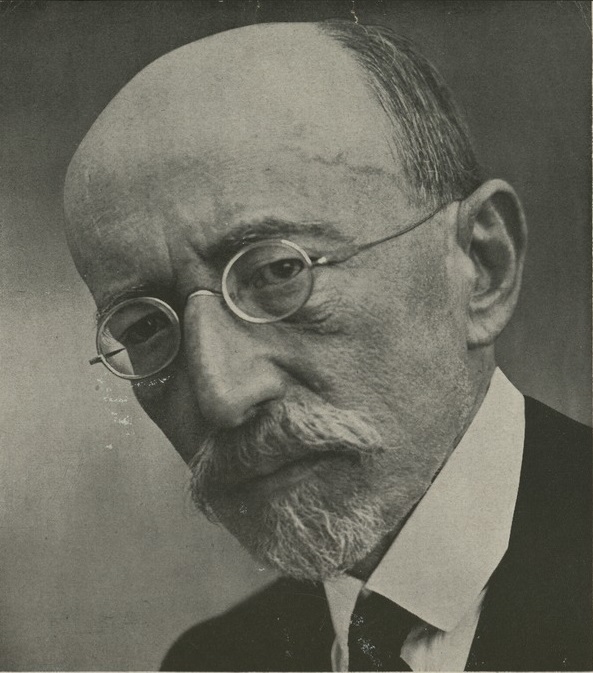

Original Zionist Idea author Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg

The Zionist Idea, published in 1959, was a tour de force for the young rabbi Arthur Hertzberg. He assembled the core writings of more than three dozen Jewish thinkers who began making the key arguments for the necessity of a Jewish State. In his masterful 100-page introductory essay, Hertzberg explained how two cathartic realisations in the late 19th century led to a new Jewish longing to establish Jewish sovereignty in the land over which King David reigned. First, that the European Enlightenment could not deliver on its promise of genuine emancipation to the Jews, and second, that Jews could never feel safe in the Diaspora, as evidenced by the wave of pogroms that spread across Eastern Europe.

I first encountered the book as a high-school senior writing an essay about Zionism and later read it in full at Columbia University, where I was a student of Hertzberg’s before serving as his research and teaching assistant for several years. What I learned from him was that Zionism is a natural outgrowth of Judaism’s bifurcated quality as both a religion and a national identity. And there was no room for that national identity in post-Enlightenment Europe. As Comte de Clermont-Tonnere famously made clear in a speech to the French National Assembly in 1789, “the Jews should be denied everything as a nation, but granted everything as individuals.”

When Hertzberg published The Zionist Idea, Israel was barely a decade old. It was still a land of pioneers and socialist kibbutzim, and its newest immigrants were mostly survivors of the Holocaust and Jews fleeing North Africa. Israel had been tested in battle twice, first in its 1948 War of Independence and then in the Suez Crisis eight years later, and both times the nascent Israel Defence Forces had overcome US arms embargoes to vanquish much larger foes. The American Jewish audience, for whom Hertzberg was writing by and large, romanticised the new Jewish state in terms that would become familiar to millions the following year with the successful screen adaptation of Leon Uris’s Exodus – with a blue-eyed 35-year-old Paul Newman the embodiment of every Israel-born sabra.

In the six decades since Hertzberg published his book, the State of Israel has grown into a mature nation, and both the meaning and nature of Zionism has changed. In 1959, only 15% of the world’s Jews lived in Israel. Today, Israel is home to 45% of the total Jewish population. And while Israel is still surrounded by the same Arab nations it was half-a-century ago, today it has peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan, and even somewhat friendly relations with Saudi Arabia. The image of Israel in 1959, despite its early military successes, was still one of an underdog nation inhabited predominantly by refugees – and for many, Jews and non-Jews alike, Israel’s legitimacy was based largely on the fact that it had been founded out of the ashes of the Holocaust. Today, Israel is a nuclear power with one of the most robust economies in the world.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the unparalleled success of the State of Israel, “Zionism” has become for many a dirty word. Though Israel is the only liberal democracy in its region, it is subject to much harsher criticism of its conduct than any of its neighbours – even those nations where male homosexuality is punishable by death (Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) and where female genital mutilation is the norm (Somalia and Egypt).

On college campuses across the United States, in the halls of the United Nations, and indeed in polite company throughout much of Europe, to call someone a Zionist is akin to using the N-word, only socially acceptable. In Hertzberg’s day, Zionists were seen as advocates for a powerless people in search of a home. Today Zionists are often equated with colonialists, and Israel is regularly accused of being an apartheid state.

Prof. Gil Troy: Following in Hertzberg’s footsteps

It is therefore a propitious time for Gil Troy, a professor at Montreal’s McGill University, to provide us with an updated version of Hertzberg’s volume. The Zionist Ideas borrows from Hertzberg and divides the voices in his anthology into the same five basic schools of thought that Hertzberg used – Political Zionism, Labor Zionism, Revisionist Zionism, Religious Zionism, Cultural Zionism – while adding the new category of Diaspora Zionism. Troy includes far more voices than did Hertzberg, with more than 140 new entries. He breaks these down into three overall categories. There are “pioneers”, who were involved in founding the Jewish State; “builders”, who participated in the modernisation of the state in the second half of the 20th century; and “torchbearers”, who are involved in a reassessment and reinvigoration of the Zionist idea.

In his introductory essay, Troy observes that by 2000, just a little over a century after Herzl convened the first Zionist Congress in Basel, “the scrappy yet still controversial Zionist movement had outlived Communism, fascism, Sovietism, and Nazism.” Why this is so is just one of the many themes of this rich trove, in which questions are posed and answers are offered across the years.

Consider, for example, the lament of Peretz Smolenskin, a Russian-Jewish nationalist whose writings in Hebrew rejected the possibility of Jewish assimilation in Europe. Smolenskin bemoaned the fact that “we have no sense of national honour; our standards are those of second-class people. We find ourselves… exulting when we are tolerated and befriended.” A century later, however, Menachem Begin presented his newly elected government to the Knesset in 1977 and proclaimed that “the government of Israel will not ask any nation, be it near or far, mighty or small, to recognise our right to exist… It would not enter the mind of any Briton or Frenchman, Belgian or Dutchman, Hungarian or Bulgarian, Russian or American, to request for his people recognition of its right to exist.”

Nor is the issue of antisemitism ever far from any discussion of Zionism. Troy includes an essay by Anne Roiphe, the prominent feminist writer, who observed that “all Jewish rivers run toward Israel… Zionism is then the yearning for completion – for the righting of a historical injustice – a response to the ever-present insanity of anti-Semitism.” And, of course, Troy recognises that even though the Zionist dream was fulfilled by the creation of a sovereign Jewish state, the challenges facing Jews have by no means dissipated. As Hertzberg wrote in a 1977 essay: “We now do battle in our own name; we have the capacity to receive Jews into a Jewish state if that need should arise… On the other hand, we are not ‘like all the other nations.’ Our uniqueness has not ended. It has only been recreated through different means.”

One of the ever-present issues is the relationship between the Jews of the Diaspora and Jews of Israel. From its inception, Zionists were ambivalent about the Diaspora. Some Zionist thinkers envisioned a symbiosis in which Diaspora Jews would support the Jewish state, while the existence of a Jewish state would elevate Jews worldwide. Others simply denigrated the Diaspora, maintaining that Jews could only fulfil their potential in their own nation.

Ahad Ha’am: Considered the father of cultural Zionism

Ahad Ha’am, the father of Cultural Zionism, recognised in the late 1890s that “not all the Jews will be able to take wing and go to their state,” but he prophesied that “the very existence of the Jewish state will also raise the prestige of those who remain in exile.” And for many Jews around the world, that has been the case. The early Zionists understood, however, that for their state to succeed, Jews from around the world would have to immigrate to Palestine. And thus a natural tension was born.

A generation after Ahad Ha’am, as the Nuremberg laws began to infect the life of Jews in Germany and Hitler’s Nazi party began its preparation for war, the Revisionist Zionist Vladimir Jabotinsky could not contain his contempt for the impotence of European Jewry. “Eliminate the Diaspora,” he warned in 1937, “or the Diaspora will surely eliminate you.”

The question of what it meant to create a Jewish state is another of Troy’s animating themes. At the inaugural ceremony of the Hebrew University in 1918, the poet Haim Nachman Bialik presaged Jabotinsky’s concern: “A people that aspires to a dignified existence must create a culture; it is not enough merely to make use of a culture – a people must create its own, with its own hands and its own implements and materials, and impress it with its own seal… But as whatever the Jew creates in the Diaspora is always absorbed in the culture of others, it loses its identity and is never accounted to the credit of the Jew. Our cultural account in the Diaspora is consequently all debit and no credit.”

It was Ahad Ha’am’s belief that a Jewish state would “become in the course of time the centre of the nation.” And there is no question that Israel is well on its way to becoming not only home to a majority of the world’s Jews, but the epicentre of Jewish culture. Troy illustrates this by incorporating an excerpt from an essay by A.B. Yehoshua, one of Israel’s leading novelists and essayists. “A Talmud lesson in a yeshiva or at an institute like Alma, the self-described home for Hebrew culture, has no more ‘Jewish identity’ than a debate by the Committee to Prevent Road Accidents,” Yehoshua wrote. “Any differentiation between them is artificial and dangerous. Because Israeliness is what brings about a total integration between matter and spirit.”

Troy also introduces us to American Jewish Zionist voices that riff on the same theme, like that of Martin Peretz, former publisher of the New Republic: “There is no greater measure of success of Zionism, finally, than the phenomenon of post-Zionism. What really gnaws at the post-Zionist scholars and writers is the spectacle of a Jewish society in which Jews are not always brooding about cosmic questions, in which they sit at cafes, dance in the moonlight, eat good food, make piles of money, chatter on cell phones, have film festivals – all of the activities of an unafraid and unanguished people.”

Troy reminds us that Hertzberg was fond of Oscar Wilde’s line that “there are two tragedies in the world – one is not getting what you want and the other is getting it.” The reality is that nationhood is complicated. And creating both a Jewish state and a liberal democracy in a nation where more than half the Jewish citizens come from nations with no democratic tradition and nearly a third of the residents are not even Jewish has proved complicated and at times ugly.

Troy is not afraid of the messiness of the Zionist project. He recognises that any serious assessment of Zionism in 2018 must include a discussion of the settlements and the occupation, as well as the civil rights and civil liberties afforded to Israel’s Arab residents, just as it must also include a discussion of the role of religion in public life – another area where Israel’s commitment to liberal democracy is being tested daily.

He includes a speech given by Rabbi Zvi Ehud Kook on the 19th anniversary of the founding of the state (only weeks before the outbreak of the Six-Day War). Rabbi Kook, who became the spiritual leader of the settlement movement, describes his torn feelings on the day of Israel’s independence and explains why he did not join in the jubilation. “I sat alone and silent; a burden lay upon me.” He was referring to the burden of a divided land. “Where is our Hebron – have we forgotten her?! Where is our Shechem [Nablus], our Jericho – where?” In sharp contrast to the messianic dreams of Rabbi Kook, Troy quotes Amoz Oz, Israel’s most famous living author, who declared, “I am a Zionist in all that concerns the redemption of the Jews, but not when it comes to the redemption of the Holy Land.”

Troy’s contributors also grapple with the goal of most of Israel’s founders that the state be both Jewish and democratic. These twin objectives are rooted in Israel’s Declaration of Independence. The phrase “Jewish State” appears five times in the document. At the same time, though the word “democracy” doesn’t appear in the Declaration, the aspiration of the state to be a democracy is made clear through the references to “freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture,” and to the document’s promise of “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex.”

Troy also offers a countervailing view from Shulamit Aloni in 1997: “I hate applying the notion of ‘Jewish’ to my identity as a citizen. For that, I prefer ‘Israeli,’ because Israeli is both Jewish and sovereign, with the notion of sovereign entailing responsibility and commitments… The term ‘Jewish identity’ reflects a closed clannishness.”

As early as 1937, Jabotinsky made clear that his solution for achieving both was simply to ensure that the Jews always maintain a majority of the population in Palestine: “There is no question of ousting the Arabs. On the contrary, the idea is that Palestine on both sides of the Jordan should hold the Arabs, their progeny, and many millions of Jews. What I do not deny is that in the process the Arabs of Palestine will necessarily become a minority in the country of Palestine.”

That is easier said than done. Today, while Jews constitute about 80% of the population of Israel proper, if one includes the territories captured by Israel during the Six-Day War, the Arab and Jewish populations are nearing parity.

At its core, Troy’s anthology is an invitation to readers to consider what it means to be a Zionist, especially in the 21st century.

Yehoshua writes that “a Zionist is a person who accepts the principle that the State of Israel doesn’t belong solely to its citizens, but to the entire Jewish people.” Yair Lapid, the media star turned politician, wrote a poem in which he basically described himself as a link in a chain: “I hold on not only to the rights of our forefathers, but also to the duty of the sons.” And there is Ellen Willis, the far-left feminist who came to her Zionism when she determined that she was “an anti-anti-Zionist.”

The Arthur Hertzberg I knew was a Zionist to his core, and he was immensely proud of the rabbinic legacy from which he descended. But he was also a liberal 20th-century American Jew who regularly told me that the Zionist pioneer who influenced him the most was Ahad Ha-am, because “the Hebraic values being revitalised and created by the renascent national culture would provide stimulation for all the Jewish world.”

Jay P. Lefkowitz, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis, served in the George W. Bush administration as the special envoy for human rights in North Korea. © Commentary (www.commentarymagazine.com), reprinted by permission all rights reserved.