Australia/Israel Review

Bibilo File: Aly’s Appeal

Oct 1, 2007 | John Levi

People Like Us: How arrogance is dividing Islam and the West

by Waleed Aly, Picador–Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2007. $32.95

By John Levi

Urbane and articulate, Waleed Aly is Australia’s most accessible voice of the Muslim community. Married to a convert to Islam, the Melbourne born and educated lawyer, has worked up a tremendous profile in the media despite his relative youth. This is a tribute to his excellent communication skills, but is also a sign of the degree to which the media in Australia hungers for an articulate, moderate Muslim voice like his. Though lacking a PhD or other relevant academic qualification, he has recently taken up a position within the Global Terrorism Research Centre at Monash University, while this year the Bulletin magazine has listed him as one of Australia’s “Smart 100”.

People Like Us is neither history nor theology. It is a passionate and well- intentioned appeal for understanding across the political and theological chasms that deeply divide “us” from “them”. The “us” is of course the non-Muslim world. Each chapter of Aly’s book presents a running commentary on the most frequently asked questions that inevitably bedevil those of us who are not Muslims. As he writes, “It is one of life’s great truths that confident, successful people are usually secure enough within themselves to be open to the thoughts and experiences of others.”

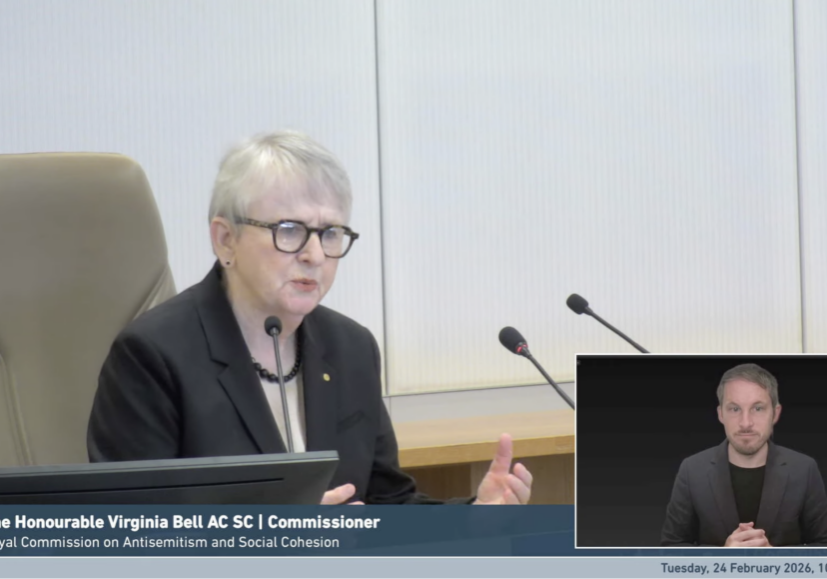

|

| Waleed Aly: Much in demand |

Both Jews and Christians have reason to be very sensitive about the religious claims of a billion-and-a-half people who believe that we have corrupted their most sacred texts and misled the world. In Islamic history, Jews and Christians were dhimmis who could never be treated as equals. Sadly, any 21st century dialogue has to be conducted beneath the shadow of a nuclear threat. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad describes Israel as “Satan’s standard bearer” and awaits the victorious arrival of the Hidden Imam. Yet, despite some chilling characterisations of Jews in the Koran there are also startling similarities between Judaism and Islam.

Arabic and Hebrew stem from a common Semitic source. Muslims and Jews both believe in an invisible unique and indivisible God. Both believe that the soul comes pure from God and that human beings do not need to be purged from original sin. Religious authority is invested in teachers and not priests. We share ceremonial laws about food. We both circumcise our boys. We each have a body of sacred literature which demands commentaries. For seven hundred years, almost all the Jews in the world lived in Muslim lands and Hebrew grammar, poetry and Jewish philosophy were shaped by that experience.

We should be soul mates, but sadly we are not.

Waleed Aly describes his own diagnosis of our dysfunctional relationship as “a snapshot of a single intellect”. He believes that the Western world is egocentric and arrogant – assuming that in a simplistic way we perceive everyone outside our Western world as black and white, reflecting the Euro-centric binary method of categorising everything as either true or false. By contrast the Middle Eastern and biblical world view believes that reality is multi-layered and complex. Aly warns us that Islam (and/or Judaism) cannot be divorced from its environment and that the separation of Church and State within a non-Christian environment has little or no meaning. Jews can respond to this observation because we know that many Israeli Jews grow up in a Hebrew speaking environment, celebrate festivals, learn Bible in school, light candles on Sabbath eve, celebrate Passover, yet paradoxically choose to call themselves “secular” or “non-religious”.

People Like Us begins with the story of the Danish cartoons as a snapshot of our dysfunction. The rights of free speech and freedom of the press are taken for granted by the West. Not so in the Muslim world, which reacted with fury, economic boycotts and riots and concluded with the Teheran “Holocaust Conference”. As Aly perceptively comments, “Suddenly the Jews, who had nothing to do with this circus, were dragged into it only for the purpose of being insulted.” It is a depressing picture but it gets worse because the book then briefly tells the painful story of the relationship between Muslims and Christians. Today Muslims are convinced that they have been demonised, alienated and disenfranchised by the West. Jews will easily recognise the observation, “Where your identity is one of differentiation, any attempt to look for points of connection, to build bridges, very quickly becomes an act of treachery.”

Paradoxically Aly, a child of Western enlightenment, denies that he is a “moderate”. The reason he gives for this is curious and, in my opinion, difficult to sustain. He asks how the label “fundamentalist” can be made to apply within an Islamic context because Fundamentalism was an American Christian religious movement that began in the 1920s.

Fundamentalism displaces reason and has an ancient history. Fundamentalists believe that they know exactly what God wants them to do. Religious fundamentalists deny the findings of science, archaeology and astronomy. Religious fundamentalists burnt Jews and Muslims at the stake. The “religious police” who patrol the streets of Saudi Arabia are the inglorious enforcers of a fundamentalism light years away from Waleed Aly’s faith. As he explains, “There is, in fact, no singularly coherent Muslim community” and he resents the popular belief that Islam is monolithic. We could add that Jews share exactly the same fate.

When Aly dips into Islamic history he is proud to see “vibrancy, diversity and passion” and he treasures this intellectual ferment, which, incidentally, also left a deep imprint on the course of medieval Jewish philosophy and religious life and liturgy. Today, in contrast to the world of Islam, most Jews and Christians clearly recognise that there are cherished rules and ancient ideas which now demand reinterpretation. The struggle to emancipate women from deep and ancient religious taboos comes to mind. So too does the on-going battle to abolish slavery despite the many explicit biblical passages that condone it. Many Muslims are not ready to concede that sacred texts can err or that a 7th century teacher, now revered as a prophet, was a child of his time who may have been fallible. Waleed approvingly quotes ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, the cousin of Muhammad and fourth caliph, who taught “the Koran is written in straight lines between two covers. It does not speak by itself. It needs interpreters, and the interpreters are human beings.”

It is moving to note that in the autobiography of a young Muslim Australian lawyer there are affectionate references to Jews. The book itself opens in the legal chambers of Justice Joseph Kay and virtually concludes with the story of Yasmine Ahmed who worked as a legal associate of South Australian Supreme Court Judge John Sulan. Aly denounces anti-Zionist conspiracy theories and deplores the “inexcusably large level of popularity” in Islamic bookstores of the “discredited and bigoted propaganda tracts” such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Henry Ford’s The International Jew. Aly is scornful of the public antisemitism of supporters of the extremist organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir, describing their attitudes as “insular” and “arrogant”.

Two thousand years have passed since Jews have spoken of a holy war (Milchemet Mitzvah). No Salvation Army band plays “Onward Christian Soldiers” anymore. However jihad in the form of an ongoing struggle for the establishment of a universal Islamic empire (or caliphate) cannot be so easily dismissed. Aly does his best and is horrified by the “warped” use of the term (jihad) to describe banditry and brigandage. He believes “Terrorism… is an act of rampant disbelief” which “denies God’s ability to restore justice and reward the oppressed.” And Aly admits, “Modern Islamic thought has a crisis to confront. It is, of course, dangerously naïve to presume that terrorist activity is purely an ideological product… Radicalism appeals to those with a revolutionary zeal”.

While Aly does not discuss Israeli-Palestinian issues at any length, there is no sign that his respect for Jews or his stance on terrorism breaks down on this frontier. Aly implies that he accepts the legitimacy of Israel and Zionism. And there is no hint here anywhere that Aly subscribes to the obfuscation sometimes adopted by apologists for Palestinian terrorism – condemning terrorism in principle, but playing word games to deny Palestinian attacks constitute terrorism.

People Like Us concludes with a call for tolerance brought about by our common humanity and the fact that we are the complex products of our own personal religious, social and political history. Aly writes, “It requires Western commentators looking at a veiled woman to see more than oppression and Muslim critics looking at Michelangelo’s David to see more than nudity.” His book is an important first step in a badly needed honest dialogue between Australian Muslims and their neighbours.

![]()

Rabbi Dr. John S. Levi is Rabbi Emeritus of Temple Beth Israel in Melbourne, and also an historian whose books include Australian Genesis: Jewish Convicts and Settlers 1788-1860 and most recently These Are The Names: Jewish Lives In Australia 1788-1850. He is also a member of AIJAC’s editorial board.

Tags: Antisemitism