Australia/Israel Review

A Second Iranian Revolution?

Oct 28, 2022 | Ray Takeyh

Why this round of protests appears different

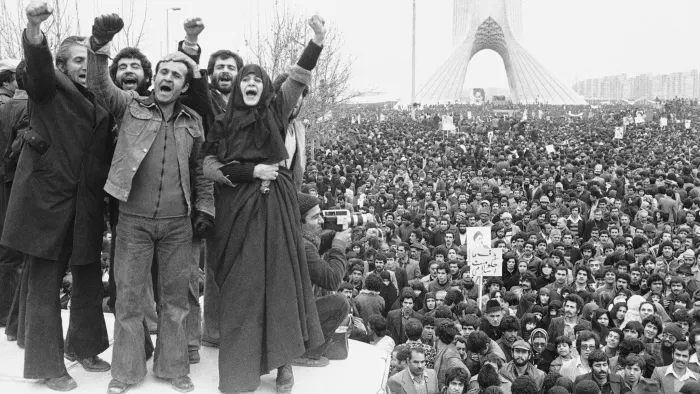

The strange echoes of the 1970s over the past 18 months – with runaway inflation, an energy crisis, and an expansionist Russia – were startling enough. And then a revolt began in Iran, just as one did at the start of 1978. It features an ageing autocrat who’s dying of cancer and overseeing a rebellious nation that has tired of his rule and the corruption of his cronies. History may not repeat itself, but it is surely rhyming in the streets of Teheran. And indeed, the best way to chart the possible trajectory of the current Iranian revolution is to look to the last one.

“Iran, because of the leadership of the Shah, is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world,” said US President Jimmy Carter during a visit to Iran in 1977. Although Carter’s unfortunate toast would be much ridiculed in the years ahead, it is important to note that until the last days of Mohammad Reza Shah’s Pahlavi dynasty, Western chancelleries and intelligence services, as well as the foreign-policy intelligentsia, were united in their belief that somehow the cagey monarch who had weathered so many crises would survive the latest one.

Behind the glitter of a rapidly modernising and increasingly wealthy elite, Iran of the 1970s was a land of discontent. The corruption of the ruling class, the provocative social cleavages that oil wealth suddenly generated, and the frustration of working in a system that discounted merit in favour of patronage and nepotism, led many to join the rank of the opposition. In a paradoxical manner, the Shah was bedevilled by his own success. He created a modern middle class but then refused to offer it a meaningful venue for political participation. His compact with his people was a transactional one, in which he exchanged financial rewards for political passivity. Even if Iran had not experienced a steep recession in the mid-1970s, this bargain would have been unsustainable. The Iranian masses wanted a say in how their nation was governed. Even more striking, the crass Westernisation had a vast swath of the Iranian public eager to restore the central place of Shi’ite tradition.

Iran’s 1979 Revolution: Hopes it would bring cultural authenticity, a stable economy and participatory politics were dashed by the development of theocratic absolutism (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Every revolution needs a spark, a watershed event after which things are not the same. In the early days of the Iranian revolution, which began in earnest in October 1977, the Iranian people were not calling for the disbanding of the monarchy but rather for meaningful constitutional reform. They wanted a free press, free political parties, and free elections. The intelligentsia wrote letters and petitions, the university students tore up their dorm rooms, the mullahs called for respecting religion in public life, and demonstrations were small and sporadic. In exile, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini thundered as the storm gathered.

This all changed in August 1978. On Aug. 9, terrorists set ablaze Rex Cinema in the city of Abadan and killed 479 people. This was the most egregious act of arson in Iran’s modern history. Exiled in Iraq, Khomeini did a masterful job of blaming the Shah for the fire even though it was later revealed that Khomeini’s own followers were responsible. The Rex Cinema bombing was an inflection point in the history of the revolution prior to which, only the hardcore opponents of the Shah had participated in demonstrations. Now many fence-sitters began tilting toward the opposition. The size of the marches grew by the thousands as Iran’s uprising became a popular revolt with Khomeini as its leader. The Shah’s belated promises of reform were swept aside as no one could trust a leader who set his people on fire.

As significant as street protests were, it was the nationwide strikes that crippled the monarchy. A dynamic country suddenly went dark. Newspapers stopped publishing, electricity flickered, bazaars shut down, banks stopped processing transactions, and ports were filled with unprocessed cargo. Most importantly, Iranian oil production came to a halt. The country stopped functioning. In his palaces, the Shah, who was dying of cancer, brooded more than plotted and concocted various conspiracy theories to explain his predicament.

In the White House, Carter assured himself that even if the Shah had lost his will, Iran’s armed forces could be counted on to restore order. He was not alone in this misapprehension, as most observers of Iran believed that the formidable army would take control. Too often, we ignore the fact that national armies don’t like shooting their own people. Battling foreign enemies and suppressing ethnic uprisings are different from going into neighbourhoods day after day and killing civilians. A determined national protest movement can erode the morale of an army, shatter its cohesion, and lure conscripts away from their unenviable task of killing their countrymen.

The Shah fled, his army crumbled, and the revolution triumphed as one of the great populist revolts of modern history. It was all things to all people. For liberals, it was a chance to construct a representative government that was accountable to its citizens. For the devout, it was an opportunity to forge an order in which religion informed politics. Islamic canons were seen as flexible enough to accommodate both faith and freedom. The Islamic Republic was to offer the hard-pressed masses cultural authenticity, a stable economy, and participatory politics. No one thought of theocratic absolutism as the endgame – except the clerics in charge.

The durability of the current Iranian regime cannot be attributed simply to brute force. The genius of the system is that it contains within its autocratic structure elected institutions that have little power but that still provide the public with some means of expressing their grievances. In the absence of such a safety valve, however superficial, the mullahs would have confronted even more protests than they have over the past two decades. The theocracy bears all the hallmarks of a dictatorship, but it has also maintained a thin veneer of collective action.

To become a revolutionary and risk one’s own life for a cause that seems distant, if not improbable, is one of the most crucial decisions a citizen can make. All social protest movements battle against great odds; history has shown that most revolutions fail. The Islamic Republic offered the masses the opportunity to participate in the national scene, but cleverly hemmed them in on all sides with clerical bodies who vetted candidates for public office. Still, when an average citizen is faced with the choice of rebelling against a vicious system or casting a ballot that will have a limited impact, he or she will probably opt for the latter.

The regime has had lively elections in which a diverse range of candidates made all sorts of promises. In the 1990s, Mohammad Khatami captured the national imagination by pledging to harmonise religious precepts with democratic norms. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is best remembered for his crass denials of the Holocaust – but at home he spoke of fair wealth distribution. More recently, Hassan Rouhani insisted that his nuclear diplomacy would generate foreign investment and revive Iran’s moribund economy.

But none of these dreams materialised, and Iranians today are bereft of delusions. They know the theocracy remains in the grip of an unelected few and is drowning in corruption. The current uprising shows that the head mullah, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, forgot the most essential lesson of the Shah’s demise – that, at times, desperate masses have little choice but to revolt.

The 2021 presidential election is likely to be remembered as the most consequential in the history of the Islamic Republic. As Khamenei, suffering from cancer, contemplated his succession, he sought to ensure a republic manned by his most reliable henchman and an economy immune to foreign sanctions. There was not even the pretence of a competitive race, as conservative stalwarts such as former speaker of the parliament, Ali Larijani, were disqualified from running. The presidency went to Ibrahim Raisi, a laconic and unimaginative mass murderer who had spent his life manning the regime’s dungeons. A sullen citizenry battered by a mismanaged pandemic watched all this with considerable angst. Khamenei’s attempt to cement his legacy began to undo his republic.

From its inception, the Islamic Republic has faced protests. Liberals, secularists, student activists, disgruntled clerics, and middle-class elements have all turned against the state at various points. The regime’s leaders were quick to dismiss all of it. They believed that the students had been seduced by America’s cultural temptations. They thought the middle class focused too narrowly on its material wealth and was therefore unable to see the true benefits of the divine republic. To them, liberals are mere apostates.

But there was something new and dangerous about the demonstrations of the past few years. This was the revolt of the poor.

As he embarked on his latest confrontation with the West, Khamenei sought to fashion an economy that would be lean and self-reliant. The American sanctions imposed after then-US President Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 were presented as a blessing; they would force the state to put its house in order and trim the subsidies that were draining the treasury. In yet another miscalculation, the regime assumed that the poor, the primary beneficiaries of the welfare state, would once more sacrifice on behalf of the revolution. This was, after all, a revolution of the oppressed, waged in their name and for their salvation. Unlike the upper classes, the poor were the essential pillar of the republic. But in both 2017 and 2019, the poor took to the streets, calling for the overthrow of the regime.

The challenge for the clerical oligarchs was to dispatch a conscript army to shantytowns that were culturally familiar to them. The fearsome Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC, may be manned by an indoctrinated class of officers, but Iranian foot soldiers are still largely drawn from the pool of draftees. The average conscript may relish beating up pampered university students but would have a tough time turning on his own. The regime enforcers understood this and developed a clever containment strategy. A quick show of violence would be followed by disabling social media and thereby cutting off the demonstrators from one another. They would then wait for the protests to peter out. The immediate demonstrations were eventually quelled – but the cause of discontent lingered.

In the summer of 2022, an unusually divisive spirit seemed to descend on Iran, and the state and society moved in completely different directions. The mullahs were preoccupied with their nuclear gamesmanship, economic tinkering, and the re-imposition of severe religious strictures. In the meantime, ordinary Iranians were protesting: Teachers protested about their pay, retirees about their benefits, farmers about lack of water, and women about their mandatory attire in stifling heat. As in 1978, economic anxiety, social envy, and political disenfranchisement became powerful forces directed against the regime. The Islamic Republic had done it to itself. All channels for political expression were blocked by a corrupt and arrogant ruling elite that was demanding discipline and sacrifice.

And then came the spark. On Sept. 16, 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini, who had been arrested by the morality police for wearing her hijab improperly, died in custody. Her senseless killing symbolised the cruelty of clerical rule. Cities, provinces, and towns were suddenly engulfed in protests. The chants of “Mullahs get lost” and “We don’t want your Islamic Republic” echoed throughout the country. The old playbook for containing the demonstrations did not seem to work, as the conscripts were asked to shoot women. They hesitated; the demonstrations persisted. Iran’s Chief Justice, Gholam-Hossein Mohseni-Eje’i, is reported to have complained that the security forces are “tired and broken, with very low morale.” A semblance of normalcy may yet return to the country, but Iranians of all classes and genders have lost their sense of fear.

Iranians have found creative ways to show defiance of the clerical regime (Image: Twitter)

The events of this summer seem eerily similar to those of 1978. Amini’s murder provoked a sense of national outrage like the bombing of the Rex Cinema. As with the monarchy, the regime has lost its narrative and its bearings. Ali Khamenei has said, “I openly state that the recent riots and unrest in Iran were schemes designed by the US, the Zionist regime, their mercenaries, and some treasonous Iranians abroad who helped them.” The Shah thought and said the same things and dispatched his diplomats to ask the Carter Administration why the CIA was plotting against him. In an ominous sign for the regime, in September 2022 the nation’s oil workers issued a statement: “We support the people’s struggles against organised and everyday violence against women and against the poverty and hell that dominate the society.” A young revolutionary at the time of the last Iranian revolution, Khamenei surely recalls that it was strikes that crippled the monarchy and hastened its collapse.

Today, the regime seems to be taking comfort in the fact that at this point there is no charismatic personality or political party leading the opposition. A revolution, after all, needs revolutionaries. And the mullahs are still in command of an array of security organs. But these are thin reeds. The longer the protests linger, the more they are likely to generate leaders who will take charge of the movement. In the meantime, every day, the mullahs will ask their taxed military to kill poor people and unarmed women. If the regime has only the army as its mainstay of support, then it has little in the way of national strength. The Shah had a well-armed military and a seemingly all-knowing secret service, SAVAK, but their combined might could not contain a movement seeking change. The records of the Pahlavi monarchy published by the Islamic Republic reveal that the Shah’s generals were most alarmed about the cohesion of their conscript army dispatched to the streets to quell peaceful demonstrations. It is entirely possible that similar conversations are taking place today in the regime’s corridors of power.

The Islamists have made nearly all the same mistakes as the monarch they overthrew. The regime lacks an appealing ideology and shields itself in rhetoric that convinces no one. It is led by a corrupt and out-of-touch elite that relies on conspiracy theories to justify its conduct. It has pursued a foreign policy whose costs are more apparent than its benefits. And the mullahs have forgotten the most essential lesson of their revolutionary triumph: Persian armies don’t like killing their own people en masse.

The new Iranian revolution may have begun, we just don’t know it yet.

Ray Takeyh is a senior fellow at the US Council on Foreign Relations. © Commentary magazine (www.commentary.org), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iran