Australia/Israel Review

The Last Word: The Devil’s Numbers

Nov 5, 2019 | Jeremy Jones

In 1988, Sheikh Taj El-din al-Hilaly delivered an overtly antisemitic diatribe at a publicly-advertised event in Sydney.

Much to the concern of the Jewish community and beyond, there were no state or federal laws in place which would have brought about any consequences to the speaker.

Of even greater concern was the number of journalists and politicians who rationalised or downplayed the importance of the hate-filled comments from a “religious leader”.

This is not to say that he was free from condemnation – just that individuals who either shared his anti-Jewish sentiments, or believed there was political value to them in having this man as an ally, ran roughshod over what was morally good for Australia.

In the 1990s, following a series of seemingly unrelenting incidents of harassment of Jewish people going to and from synagogues in Melbourne, some community members declared they felt unsafe living as Jews in Australia – sentiments which would not have been mollified by seemingly half-hearted reassurances from public figures.

In Sydney, in the last two decades of the twentieth century, there were terrorist bombings of a major Jewish cultural institution and the Israeli Consulate, and so many arson attacks on synagogues that the Harbour City temporarily had the distinction of being the city with the most arson attacks on synagogues in the post-World War II world.

There is a real difficulty in talking about increases in reports of incidents of antisemitism as if this is a direct reflection of the seriousness of the issue and how it affects the lives of Jewish Australians.

The bullying of a schoolchild, a speech by an anti-Jewish religious leader, an arson attack on a synagogue, the random punching of an identifiably Jewish person in a public place, graffiti on private property in a neighbourhood not known for its Jewish presence, an email threatening harm on specified individuals, posters promoting the world view of an antisemitic group plastered on synagogue gates, a teacher promoting anti-Jewish stereotypes in a classroom, and Holocaust denial mailed to a survivor of the Shoah – each is one “incident” of antisemitism, making numerical aggregations of such incidents almost meaningless.

Even when one divides the incidents into vandalism, harassment and so forth, vandalism could include petrol bombs thrown at synagogues or ripping mezuzahs off doorposts, harassment could include threats and abuse yelled out the windows of passing vehicles or threats by a known person standing centimetres from the victim. To my knowledge, no one has developed a system of weighting incidents in a way which would result in a meaningful mathematical descriptor of the state of antisemitism.

From 1990 to 1999, reports of antisemitic incidents in Australia increased by over 60%, with reports of physical violence and face-to-face harassment more than doubling.

The increase of over 65% from 2001 to 2002 was mostly due to hate mail.

From 2017-2018, the increase was just under 60%, with the big growth in incidents related to stickers, leaflets and posters.

In recent weeks, a number of examples of antisemitic bullying have garnered media attention, and often been misleadingly framed as if these are examples of some form of unprecedented antisemitic activity.

It is right and proper that the incidents have drawn outrage and condemnation. It is also significant that they have been discussed in terms of existing, or now necessary, measures to both protect victims and to punish perpetrators.

A great deal has changed since the days of Sheikh Hilaly’s speech and the street harassment of Melbourne Jews. There is now a raft of federal, state and territory anti-racist legislation and coalitions of people of goodwill working to understand and combat antisemitism, complemented by a security consciousness which has contributed to the safety of targets of antisemitism.

Each and every anti-Jewish incident is one too many and should be condemned. But any assessment of antisemitism must be sourced in a holistic understanding which acknowledges changes for the better, as well as ongoing challenges to social cohesion.

Tags: Antisemitism, Australia

RELATED ARTICLES

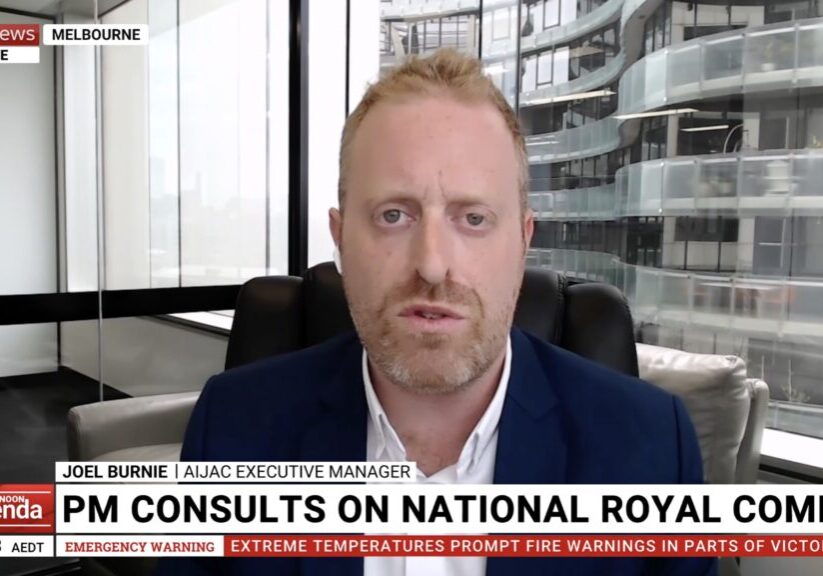

Parameters of a Royal Commission will be crucial: Joel Burnie on Sky News

Author comments part of disgusting, toxic antisemitism spreading in recent years: Joel Burnie on Sky News